The Practice and Promise of Prison Programming Justice Policy Center Sarah Lawrence

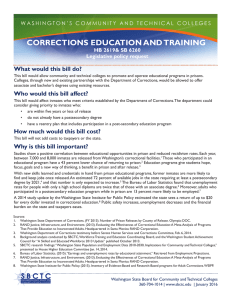

advertisement