Evaluation of Breaking the Cycle

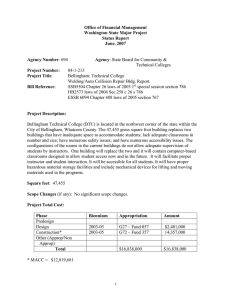

advertisement