Management as a science: emerging trends in economic and managerial theory Horst Albach

advertisement

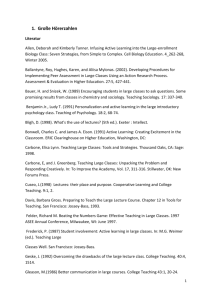

JMH 6,3 138 Management as a science: emerging trends in economic and managerial theory Horst Albach Koblenz School of Corporate Management, Vallendar, Germany, and Brian Bloch University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand Keywords Business education, Development, Management education, Trends Abstract This paper considers the scientific development of business education on the basis of five criteria: if-then statements, freedom from values, spatial and temporal validity, objectivity, and falsifiability. Methodologically, the emphasis is placed on emerging scientific and societal trends which influence scientific research and the paper is aimed primarily at academics. The paper also has an implicit politico-scientific theme. Considering the multiplicity of approaches in management education, any attempt to take an overall perspective is likely to be controversial. Specific themes include the interdependence problem, uncertainty, dynamics, the development of various theoretical paradigms and trends such as globalisation and ecological consciousness. The context of analysis and discussion is predominantly that of German management theory and, in this sense, the paper provides a different perspective from that of other English-language contributions in the area. Introduction Thirty-eight years ago, Erich Gutenberg (1957) delivered his famous lecture on ``Business administration as a science''. With this talk, Gutenberg established Business Studies firmly as a scientific discipline at German universities. He promoted the view that Management or Business Administration had established itself as a science on the basis of three fundamental complexes of questions: (1) eliminating changes in the value of money from accounting; (2) accurate cost allocation; (3) uncertainty surrounding sales-related marketing decisions. Since then, business education has taken a remarkable upswing at universities, is frequently represented by its own faculties, and graduates are highly sought after in industry. In public administration, business skills have broken the traditional (in Germany) juristic monopoly. Business education appeals substantially to young people to the extent that universities are now almost overwhelmed by the demand. The pressure from industry to provide more practical education has also largely been met. In this sense, management studies have become partly like those offered by American business schools. Journal of Management History, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2000, pp. 138-157. # MCB University Press, 1355-252X The term ``management theory'' has been used as the closest possible translation of the German ``Betriebswirtschaftslehre''. This, however, has raised doubts as to the scientific nature of business studies. It therefore seems meaningful and necessary to reconsider the scientific character of management theory. That will be done in the following two sections. In the first section, the demands of a social-science discipline will be considered. In the second section, emerging trends in modern businessmanagement theory will be measured against these demands. The next step is to distinguish between the two related scientific trends, on the one hand, and societal developments, on the other. The latter exert a significant influence on the evolution of management theory. The demands on management theory as a science For Gutenberg, the basic criterion of a science was the if-then statement. For example, the elimination of changes in the value of money from accounting allowed if-then statements to be made on the effects of entrepreneurial activity on societal welfare. The investigation of the determinants of cost facilitates statements about the dependence of cost on the level of economic activity. The results of market research allow statements to be made about the possible reactions of consumers and competitors to the marketing strategies of firms. Max Weber insisted that a science be value free, but this criterion has often been misunderstood. Freedom from values does not eliminate ``an explicit orientation towards the concrete economic and social goals which vary from firm to firm'' (Drumm, 1993). However, the values or goals should not be postulated by academics, but drawn from current market and societal realities. They form a component of the problem to be investigated and must correspond with reality. The academic or scientist does indeed work value free in this sense. The narrower the defined scope of research, the less the scientist can allege that the results are valid independently of time and space. Statements about large enterprises are inextricably bound up with the existence of the capitalistically organised economy. Statements about smaller ``firms'', on the other hand, are not so much linked to a particular economic order, but rather to the monetary element of the economy. Scientific statements must be objective. They are objective if a nonparticipating third person could evaluate and understand them. Empirical results must be replicable. However, the criteria for replicability in the social sciences can and should be less stringent than in the natural sciences. Finally, Karl Popper's theory of falsifiability should be mentioned (Popper, 1935; 1964). The rigour with which this theory was originally defended has somewhat lessened over the years, such that results are not discarded when their multiple correlation coefficient is below 0.5 and the level of significance of the regression coefficient is well below 99.5 per cent. Many scholars do not strive to find counter-examples as Popper wanted, but seek instead ``credible new paradigms'' more along the lines of Thomas Kuhn (1974). Management as a science 139 JMH 6,3 140 If-then statements, freedom from values, spatial and temporally general validity, objectivity, and falsifiability are thus the five criteria which constitute a scientific system of statement. Developments in management theory Scientific trends In the future, it can be expected that the scientific trends that were observable in academic research in the last 40 years will find their way increasingly into practical applications. This marks the major difference between the current trend and that which prevailed up to the end of the 1970s. Developmental trends in management theory in the 1960s and 1970s The 1960s and 1970s were dominated by formal extension of the theory of the firm. The classic model of the firm, which worked on the premiss of several freely available productive factors being combined into a single product and being sold in a market with incomplete demand, had proven too narrow. The multiproduct firm with interrelated production formed the focus of research in theory of the firm. The assumption that resources are freely available was dropped. Competition inside the firm for use of the various scarce resources was up to that point an unresearched phenomenon. The use of operating capital involves delicate decisions as to long-term utilisation. This is a quite distinct issue from short-term factor allocation. In the 1960s and 1970s, therefore, management theory turned its attention to three problems: (1) interdependence; (2) long-term decision making; (3) uncertainty. The interdependence problem In multiproduct enterprises, various products can be manufactured with the same machine. Quite different raw materials or finished goods can be stored on the same premises. The firm's financial resources can be used to finance a wide variety of activities. Competition for these scarce resources constitutes one side of the interdependence problem. The other side arises from the fact that production is frequently executed in multiple stages or phases. It is possible that each product follows a different order of production. That means that either partially completed products await machining or vice versa. This temporal element comprises the second component of the interdependence problem. In order to resolve this problem, the theory of the multiproduct firm was developed. Multiproduct theory can be termed general, because it determines the optimal integration of all components of the business. The theory is also objective; in principle, it is not difficult to understand. It is also empirically sound; having led to a fundamental reorientation of financial accounting procedures. Accounting and production planning are now recognised as distinct approaches to management. The problem of long-term decision making The theory of the firm treats the productive capacity of the firm as given. Thus the theory of the one-product firm with its Leontief production functions proposes production at the limits of capacity in order to achieve optimal profits. The assumption that capacity is given does not hold in the long run. Through investment decisions, capacity can be altered. Investment decisions commit the financial resources of a firm well into the medium or long term. However, investment also generates returns which can be utilised over the long term. The firm is therefore regarded as a ``going concern'' with many alternative forms of current and future funding and with multiple and varied financial sources outside the confines of the firm. Every theory that attempts to deal with this complex interaction, especially empirically, can only do so partially. Capitalvalue theory can be used if one assumes that the only interest earned and paid counterbalance over the life of an investment. If this assumption is confined to the period beyond the planning horizon, then the theory of multi-stage budgeting can be used. These theories certainly use value free and objective ifthen statements, which are also spatially and temporally generalisable. Despite the obvious ease of falsifiability, these theories have proven themselves empirically. Nonetheless, the dynamic investment theories discussed below are superior. The problem of uncertainty Long-term decisions of the firm are fraught with uncertainty. This uncertainty can be regarded as a fundamental business parameter with an impact on preferences, factor allocation and production possibilities. Alternatively, it may refer to competitors and other economic agents (Reiter, 1985, pp. 18-19). Efforts to get to grips with this problem have shown that many subjective modes of behaviour in the context of the principle of rationality are associated with uncertainty. This has led to ongoing controversy in the theory of the firm. However, it would appear that as before, because of the interdependence surrounding so many commercial circumstances, uncertainty has never been integrated satisfactorily into managerial theory. The discussion on the validity of the Bernoulli Principle is by no means resolved. The problem of uncertainty tends to go beyond the narrow issue of what decision criteria are appropriate for modelling or coping with uncertainty. The basic question as to how an enterprise copes rationally with uncertainty led to the development of the theory of risk management. Recognition of risk and the various methods of coping with it form the foundation of the theory. Amongst other things, this has led quite logically to the point of view that less intensive Management as a science 141 JMH 6,3 142 use of scarce resources today creates greater economic viability over time in an uncertain future. A current shift away from profit maximisation means greater ``flexibility'' and higher long-run profits. Game theory facilitated an early methodical handing of uncertainty as found in the work of Luce and Raiffa (1957) and Albach (1959). However, in the 1960s and 1970s, game theory failed to establish a wide acceptance within the theory of the firm. This changed radically in the 1980s (Schauenberg, 1991, p. 329). After all, the widely-accepted proof that ethical business is ultimately profitable is based on game theory (Krelle, 1992). Recent theories have indicated that the enterprise itself is an institution that serves to minimise risk, as will be elaborated on in due course. The theory of risk management in the firm is still inchoate. We can do little more in this paper than pose various if-then statements which can be tested, logically and experimentally, to discover whether they meet the various criteria of validity. Developments in management theory in the 1980s and the 1990s The 1980s and 1990s saw a development in management theory which necessitated a radical revaluation of the issue of decision making in firms. Decisions are not made by one person; delegation is often necessary and committees are frequently involved. It cannot be taken for granted that delegation will lead to the same decision that the chief executive would have made. In this light, the organisational problem of the firm has to be reconsidered. Confrontation of this issue is characterised by three main ramifications or problems: (1) dynamics; (2) information; (3) motivation. The problem of dynamics The decisions of today affect those of tomorrow. The former Shah of Persia used to speak of his ``underground bank'' and posed the question as to whether it is more favourable to produce as much oil as possible in the short run and invest the gains in order to earn interest or whether to leave it in the ground and reap the gains at some point in the future when the asset itself is worth more. This problem of inter-temporal allocation of scarce resources is of central importance. With what future reactions from clients, banks, shareholders and other interested parties must a firm reckon when it makes a decision today? How can it ensure that, despite making current decisions which appear to run contrary to profitability, the future decisions of clients are not prejudicial to the firm? And are these decisions different when considered in the light of competition or when it must be expected that competitors will have an impact on the future effects of today's decisions? The meaning of this dynamic theory of the firm can be explained by means of an example. Traditional theory teaches us that in a recession it is meaningful to drop prices to the level of marginal cost. Fixed costs will be lost, regarded as sunk costs, which have no impact on the decision; the paper losses simply have to be accepted. If the problem is formulated dynamically, it is evident that the lower price limit remains below short-run marginal costs. If it is possible, through still lower prices, to attract so many customers that higher profits can be made in the future, then high current losses can be regarded simply as an investment. However, future profits can be jeopardised by competition. For that reason, a policy of price setting below marginal cost makes more sense in a monopoly as opposed to an oligopoly. The dynamic theory of the firm makes if-then statements about the temporal effect of business decisions. These statements are objective in the sense that they follow logically from the specified assumptions. However, it is quite clear that they are not valid irrespective of spatial and temporal considerations, but linked to societal and environmental structures and variables which are strongly characterised by individualism and self-interest. With respect to the latter, the theories lay claim to general validity. The statements are value free in the sense that altruism and egoism are not judged, but regarded as polar reference points of human behaviour in a society which creates both business potential and constraints. When mathematically formulated, these statements are objectively verifiable. They are also, to a substantial degree, falsifiable. Whether or not an employee or colleague behaves loyally is also empirically testable, as is the statement that in a recession a firm should not only accept high losses, but deliberately incur them in order to gain new clients and ensure their future loyalty. The information problem In the traditional theory of the firm, it is assumed that information is freely and ubiquitously available. This factor is therefore not an explicit part of the production or cost functions which deal with planning, organisation and control (Luecke (1991) is an exception). These costs form part of fixed cost. In the latest management theory, information is taken into account explicitly. In the 1960s, an approach emerged with the premiss that the flow of information inside a department is free, but not that between departments. In team theory, information cost, profit forgone due to unsatisfied demand, storage and interest costs were considered and it was demonstrated that decentralised information systems, which consciously allow the existence of informational deficits, could provide an optimal solution to the information problem (Schueler, 1978; Marschak and Radner, 1972). Traditional theory teaches that employees ought to be given clearly defined tasks and that it is appropriate to assume that employees will execute these tasks faithfully and as intended by the employer. It is further assumed that superiors and subordinates are equally well informed and that informational asymmetry has no impact on decision making. Recognising the naõÈvete of this approach as early as the beginning of the century, Max Weber drew attention to the need for control. Much earlier, however, Charles Babbage (1835) was Management as a science 143 JMH 6,3 144 thinking along similar lines. These writers emphasised that informational asymmetry could indeed lead employees towards organisationally dysfunctional behaviour. Current dynamic theory shows that such fears are frequently unjustified. Informational asymmetry is not harmful when the relationship between superior and subordinate is based on mutual trust and confidence. If such a basis is established, it is possible to dispense with resource-depleting control mechanisms and systems. The financial savings can be paid out in the form of higher wages. Loyalty and altruism appear in the dynamic theory as the highest form of self-interest. This is an important and interesting result of the dynamic theory of the firm. Organisational theory has thus inverted Lenin's famous words ``trust is good, control is better'' into ``control is good, trust is better''. Trust is the most cost-efficient form of control in the firm. It is developed partly by sacrificing short-term profits or wages/salaries in favour of building a cooperative working climate. It is thus quite meaningful to talk of investing in ``trust capital'' in the firm. Thus trust capital is reciprocal; it flows not only in the direction of management to workers but vice versa as well. The basic condition is that tangible returns will be forthcoming in the future. The implication is that the labour contract between firm and workers loses its short-term character. It assumes the nature of a long-term partnership, which binds both groups to the firm. In the language of Institutional Theory: the labour contract regulates long-term transactions between firm and workers according to relational law. Organisational theory thus forms the basis for a societal trend that has been observed in the industrialised West for several decades: our society is mutating from capitalism to human capitalism. Recently, however, the problem of market information systems has been reformulated. In the classical theory of competition, complete transparency of information was regarded as characteristic of a perfect market. In an oligopolistic market, information gained by observing the competition was regarded as lowering the intensity of competition and thus as contrary to societal interests. Currently, game-theory approaches are being developed which deal with the question of precisely what information should be exchanged amongst competitors and under what conditions, if the process is to be beneficial to society. The results of this revaluation show that the effects on society depend not only on the type of information exchanged, but also on the market structure and the type of products being traded. Information theory in its state-of-the-art form makes a series of if-then statements which are linked to very special conditions. The theory is, however, not spatially and temporally generalisable, which presents serious difficulties in terms of empirical validation. Nonetheless, this theoretical contribution shows, like no other in recent years, how dangerous allegedly general economic theories can be when they are put into practice, without taking the postulate of falsifiability seriously. Information theory has called virtually all the statements made by classical market theory into question. The problem of motivation The diverging goals and personal preferences of members of the organisation were excluded from the traditional theory of the firm by the assumption that all employees strive to make decisions which are optimal for the firm. As soon as economists relax this assumption, they have to integrate sociological contributions to business. In this fashion, the theory of bureaucracy and motivation has become a component of management theory. Laux (1979, 1990) and Laux and Liermann (1987) posed the economicallyoriented question as to whether one can delegate at all, given the divergent goals of employees. The pervasive problem of organising a firm in the light of divergent goals had been considered to some degree in the 1970s, but was tackled with due consistency and seriousness for the first time in the 1980s. It was demonstrated that there are two basic means of coordinating the varying goals of employees so that they focus on the common goal of the enterprise: hierarchical control and monetary reward (Albach, 1974). Both cost money. The lower the commitment or weaker the ties of the individual to the firm, the higher the costs of attaining goal congruence. Medium- to longer-term labour contracts lower these costs. At the same time, however, this raises market risk for the entrepreneur, because he/she is no longer able to share risk with employees in the form of job loss. This general model of organisation of the firm is currently referred to as Principal-Agent Theory (Arrow, 1985). Without doubt, this theory provides a scientific approach to the evaluation of cooperation in organisations with diverging goals and varying levels of information that finally dispels the ``folklore'' which prevailed for decades in business-oriented organisational theory (March and Simon, 1958; Simon, 1981, p. 82). Paradigms and models Of course, the depiction of economic problems in which the theory of the firm has proven itself as a science provides only a partial view of the manifold problems which management theory as a broader discipline encompasses. In the following section, the perspective will be broadened in order to examine the developmental tendencies of the subject as a whole. The picture which emerges indicates a broad range and clearly demonstrates two trends: (1) the development of paradigms; (2) the tendency towards generalisation. The development of paradigms In the 1950s, the theory of the firm (in Germany) was centred on the productionoriented approach of Erich Gutenberg (1957). Research in the ensuing years was based on this approach. The 1970s, however, were characterised by attempts to break this pattern. A trend became evident which the sociologist David Zeaman described as follows: ``One of the differences between the natural and social sciences is that in the former researchers have attempted to Management as a science 145 JMH 6,3 146 meet the challenge posed by Newton, whereas social scientists have set about in opposition to this''. In the interim, management theory in Germany has, in addition to the productive approach, generated the following approaches[1]: . the decision oriented approach; . the systems approach; . the coalition-theory approach; . the labour-centred approach; . the behavioural-science approach; . the normative-ethical approach; . the political-administrative approach; . the information-systems approach; . the ``invisible-hand'' approach; . the negotiation-theory approach. These manifold approaches have generally been followed with little if any reference to and mostly in direct opposition to one another! What is of interest here is not the content of the individual paradigms, but the fact that there are so many ± such a variety of ways of mapping the industrial landscape. The tendency towards generalisation Management theory exhibits a remarkable tendency towards generalisation. This might seem surprising, but is in fact inherent in the trend towards specialisation which is manifest in most sciences. This is shown quite clearly by the division of articles in the Zeitschrift fuÈr Betriebswirtschaft (Journal of Business Management) over the years 1978 to 1992 (Table I). Between 1978 and 1984, the majority of articles were located in the financial area. This predominance was then superseded by articles on general business administration and organisational theory. The change reflects the overall theoretical development; increasingly, researchers adopted Principal-Agent theory as the fundamental model. The more specialised the research became, the more pronounced the trend towards generalisation within the research itself. A more subtle analysis of the publications shows quite clear ``fashions'' or ``in'' themes. Thus, in the 1960s, a series of papers with a societal emphasis emerged; since 1984, there has not been one article in this area. Innovation theory, which, as late as 1985, was an area characterised by serious deficits (Albach, 1985b) is today heavily researched and important results have emerged, such as the work of Hauschildt and Brockoff (1993). With respect to business ethics and organisational culture, what was once dismissed as a transient fad is becoming ever more an area for serious scientific research (Albach, 1992). In this area, human capital theory has exerted a constant influence. Human capital in an enterprise is not simply the sum of skills and modes of behaviour determined by the production process, but also Subject area 1978 General management Organisation 11 Personnel management Logistics and materials 3 Production P 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 % 16 18 11 13 16 19 34 19 18 16 11 13 13 17 234 16.3 6 11 10 14 12 9 16 11 12 16 26 12 16 7 189 13.2 8 5 6 5 2 14 4 7 3 4 2 4 7 4 76 5.3 1 5 2 1 3 2 - 5 8 2 4 2 5 5 48 3.4 9 4 5 2 1 3 2 - 5 8 2 4 2 5 5 57 4.0 Sales 14 14 5 11 4 12 5 12 9 6 9 6 12 11 16 146 10.2 Finance 14 43 22 21 21 17 23 5 13 11 10 12 26 14 14 266 18.6 Accounting 21 12 11 15 15 18 8 6 13 16 20 9 10 7 12 198 13.5 Managerial control - 4 5 2 4 2 1 2 4 - - - 26 1.8 Special topics 2 - - 8 12 12 13 12 10 14 10 14 16 12 14 15 15 18 198 13.8 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 1433 100.0 Management as a science 147 Table I. Articles by subject area: Journal of Business Management JMH 6,3 148 encompasses managerial values and the ethical underpinnings of workers. The education, training and development of human capital in enterprises thus relate to ethical issues. The expression ``organisational culture'', with respect to this aspect of human capital, has established a place in management theory. There would also seem to be a nod here to the roots of the business discipline, which, after all, can be traced back to the factory system and moral theology of Adam Smith. Societal trends Business management is not a science that is conducted for its own intrinsic intellectual or academic merit, but continually poses questions relating to a fundamental societal institution ± the enterprise. Management theory considers the conditions under which an enterprise loses its societal legitimacy, with the intention of establishing how this legitimacy can be maintained. In this sense, business theory is like a combination of the disciplines of medicine, science and art. The enterprise is a part of society as a whole and is thus affected directly by developing societal trends. When new trends emerge, management theory considers whether existing analytical techniques suffice in order to integrate and generally deal with the effects of the trends. If unable to do so, management theory enlarges the vistas of its scientific methods. Societal mutations therefore set in motion new developments in management theory. Five trends have recently exerted a major impact on management theory: (1) globalisation of the economy; (2) intensification of international competition; (3) pervasive influence of the social market economy (i.e. the mixed economy, market driven, but with a fairly substantial government role); (4) increasing participation of women in the labour force; (5) ecological consciousness. The significance of these trends for the development of management theory will now be considered. The globalisation of industry The development of transport and information technology, referred to as ``the globalisation of industry'', has made the world smaller. This has in turn led enterprises to be regarded as ``global players''. In the last couple of years, globalisation has become a major theme in Germany and elsewhere, particularly in relation to the effects it has had on employment (Martin and Schumann, 1996). Highly intensified international competition has led to a combination of downsizing and rationalisation of firms, on the one hand, and a relocation in lower-wage countries, on the other. This is currently changing the face of both labour markets and the local industrial scene, trends that will inevitably exert a correspondingly powerful impact on management theory. Already, these trends, and those described in the paragraph below, are reflected in the writings of O'Brian (1992) and Haggard (1995) with respect to developing countries, and that of Ohmae (1995) and Naisbett (1994) in a more northerly perspective. A few relatively large firms compete in global markets. The picture of the ``global player'' does not, however, refer to the individual major firms like General Motors or Toshiba, but rather to a new organisational form of worldwide competition. ``Global players'' are groups of enterprises which comprise component and systems suppliers, as well as consultants, trading houses and possibly banks. All these form a ``strategic family'' which competes with other ``global players''. In other words, global competition has led to the development of a new kind of inter-organisational cooperation. However, these players are not necessarily large firms, as pointed out by Naisbitt (1994), and innovative smaller firms sometimes play a key role, often but not always, within strategic alliances. It is clear, though, that the boundaries of economic units have become blurred and fluid (Passau, 1994). In order to contend with this new picture of global players, management theory has adapted the instrument of ``networks'' from the social sciences. Barrell and Image (1993) devote considerable attention to the issue of cross-border and international networking and the substantial intercultural awareness that it demands. McKenna (1991) considers the networking issue from a marketing perspective. Because transactions between individual enterprises in such a network are generally long-term, short-term optimisation strategies and tools have lost much of their significance and meaning. Traditional accounting, planning and control methods are inadequate in the context of the new networks of organisations. The standard techniques have to be expanded by long-term transaction-cost accounting and controls. Intensification of international competition The globalisation of industry has led to more intense international competition, as indicated by the proliferation of such terms as ``global marketing'' and ``global sourcing''. The latter is emerging as a major competitive mechanism (Hutmacher, 1996). International competition is based less on prices than on innovation (Sturm, 1997). Indeed, innovation is currently being hailed as the fundamental mechanism by which firms and indeed nations can retain and extend their economic clout. Because the new products of a particular firm lose their identity as innovations if they are not first-to-market, innovational competition means temporal competition. Time management has thus become an important new research area (Simon, 1989). Time management incorporates durations of research and development, production, construction and delivery (Academy of Sciences, 1993). In particular, the scientific analysis of production systems in the light of time management has led to quite new insights into industrial management. This emphasis has extended into a variety of different productive and work situations (Beyer and Beyer, 1996). For example, stock reduction highlights Management as a science 149 JMH 6,3 150 shortcomings in production flows. Very short production series necessitate a reduction in planning and preparation time (Wildemann, 1988; Kistner and Steven, 1993) and lead to the introduction of parallel finishing times. Lean production is often cited as an instrument for shortening production times but, in fact, it can be argued that in terms of production depth, it merely shifts production times on to suppliers (Reese, 1993). Only to the extent that it is linked with parallel production (not possible within one individual firm) does lean production really represent an effective shortening of production time. Nonetheless, the concept has gained considerable popularity and extended into the services sector (Biehel, 1994). The reduction of production depth thus substitutes market relationships for the former hierarchical relationships. There is a rise in the number of small, autonomous economic entities operating in the market, which mirrors the desire for autonomy in the market. However, this development is more a consequence of the intensification of international competition than societallybased drives for independence (Albach, 1989; Stadermann, 1996). Pervasive influence of the social market economy In the 1970s, the developing countries started to seek a new economic order, a ``third path'' between socialism and capitalism. In the 1980s, a remarkable degree of change has been manifest, characterised by broad recognition that the market economy has superseded the planned economy. This development is associated not only with greater material prosperity, but also with cultural richness and a reasonably efficient solution to the social problems of health care and ageing populations. The model of the social market economy has permeated the world. This fundamental change has led not only to the collapse of the socialist economies in the East, but to new developmental strategies in the South. The wide range of dialogues, stalemates and theoretical issues is considered in some detail by Helleiner (1990) and Fatemi (1994). These developments constitute a major challenge for management theory which is expected to contribute towards understanding and dealing with the transformation process. Management science must provide insight as to the optimal transition path of a former ``people's own enterprise'' into the market economy. Traditional management theory is ill equipped to cope with these revolutionary changes in society. New instruments are being developed, by which the transformation process can optimally be managed over time and with respect to the concomitant societal costs (Albach and Witt, 1992). In the German context, potential strategies are outlined and analysed by Zinn (1992), Bossle and Kell (1995) and Wuertele (1995). In this context, but within a more general framework, Murphy and Tooze (1991) suggest that there is a need for a new form of international political economy. Furthermore, the Global Modeling Project at the Matsunaga Institute for peace at the University of Hawaii is aimed at allowing management theorists and practitioners to consider a wide range of social, economic and political values (Anonymous, 1997). It is hoped that such contributions will also assist in defusing North-South conflict. Organisational theory in particular, but management theory in general, is faced with some daunting challenges. Researchers and theoreticians need not only to understand the transformation processes of enterprises from the former planned economies, but also to be able to assist in their formation and development. In Germany, this problem was greeted in 1989 with excessive and unrealistic optimism. In the interim, it has become clear that organisational transformation is a two-dimensional process. An enterprise has to adapt itself to its environment, which itself may be changing radically as in East Germany or as part of an ongoing process as in other former Eastern-Bloc countries. Christ and Neubauer (1994) examine the specifics of the East German transformation with its striking East/West disparities which have yet to be resolved and reconciled. In East-German enterprises, reorganisation initially took the form of a change in legal structure. In general, a public company or limited liability company was selected. Then, organisational changes to management structure were investigated of which privatisation, reprivatisation, management-buyouts and management-buy-ins are the best known. Finally, restructuring with the intention of ``concentrating on core competencies'' was considered. This involved determining which of the current strengths of the company were most likely to lead to long-term viability. Unfortunately, it became evident time and time again that the integration of the former socialist enterprises required access to information and know-how-networks, in order to develop elusive nonmaterial capital which is vital for international competitiveness. Futurists at the Heinz Nixdorf Institute in Germany have published a book on Scenario Management (Anonymous, 1997), in which insights of this kind are provided. The emphasis is on adapting systems thinking in a turbulent, globalised environment in which there is more than one possible competitive future. The critical factor is thus not the organisation of material capital but the organisation of knowledge in the minds of management and workers. The examination of transformation processes leads to a theory of organisation of human capital in enterprises. The analysis makes clear that this process does not simply mean returning the enterprise from the planned economy to the capitalism of the industrialised West, but a transition from what was in fact State Capitalism to something best termed human capitalism, which is not yet fully developed even in the West. Increasing labour-force participation of women The number of career women has been rising steadily for several years (Autenrieth et al., 1993). Businesses tend to react too slowly to this trend in terms of concerted and consistent action (Domsch, 1993). Demands for more part-time work, on the one hand, and for quotas of women, on the other, are being made ever more fervently. According to Edmondson (1996), between Management as a science 151 JMH 6,3 152 1994 and 2005, women will make major relative gains in the workforce. Patrickson (1994) confirms a similar shift in the male/female composition of the labour force. These are compelling problems and as such pose fundamental issues for management theory, involving the development of new forms of work organisation. The currently dominant form of labour organisation is that of the large industrial mass-production plant. This is characterised by highlydisciplined working hours and a sacrifice of individual autonomy by workers. Although this specific form of organisation is no older than 150 years, strong similarities can be found in the bureaucracies of the thirteenth century. Historically, the man carried out his profession and the woman was responsible for the family (Mayer et al., 1991, pp. 57-90). The desire of women for a career has become quite incompatible with this division of labour. The very substantial societal and attitudinal shifts have made the workplace of the 1990s enormously different from that of earlier periods, and the literature is reflecting this consciousness (Asgodom, 1993; Demmer, 1988). Those enterprises which succeed in creating temporal autonomy for women as well as men are likely to hold a substantial advantage over competitors. This and the above-mentioned demographic changes will translate into considerable market and consumer changes which businesspeople and analysts of business will increasingly have to confront and integrate in their work. Homogeneity between the sexes is not to be expected (Myers, 1996), such that the quite distinct needs and preferences of women will exert a growing impact on the market, in terms of internal business structure (Bentner and Peterson, 1996), management and consumption patterns. Management theorists are indeed integrating the development of post-industrial forms of labour organisation (Rehkugler and Voigt, 1990) into their writing to an increasing extent. Ecological consciousness Ecological awareness has also grown significantly in the last few years (Kreikebaum, 1990, 1993; Albach, 1993; Markley, 1996; Sarkis, 1995; and many others). This was certainly more prominent in the industrial West than in the socialist and developing economies. Enterprises which rail against the trend will surely lose perceived legitimacy in the long run. Integrating environmental cost into financial management is a logical extension of cost-utility thinking; environmental protection has emerged as a viable market. It is now generally accepted that environmental management is a fundamental part of business theory and application. Business organisations are increasingly being forced to consider the environmental impact of their actions and behaviour (Sarkis, 1995). Similarly, responsible executives integrate environmental considerations into their corporate culture and business planning (DeCrane, 1993; Schreyoegg, 1994). Management theory has made major strides in this direction in recent years. Sietz (1994) and Schimmelpfeng and Machmer (1995) have taken up the concept of an eco-audit and considered the costs and benefits of systematic ecological management. The growth of international trade and globalisation is ``feeding into politics and policy'' (Stevens, 1994) and indeed, the European Union has integrated such issues in a set of legislation (Oeko-Audit, 1993). This trend, though, remains more marked in production than in cost theory, in that the problem of dealing with external costs and returns has not yet been resolved fully (Albach, 1988). In marketing theory, it has at last been widely recognised that many deals are not completed upon payment, but rather upon return of the used or obsolete good. Meffert and Kirchgeorg (1997) have integrated ecological consciousness and action into standard marketing concepts and analysis. Product-cycle thinking of this kind is a new and significant dimension in business theory.There remains much to be done in this area, theoretically and even more so in practice. Nonetheless, it is clear that management theorists are now bridging the theoretical gap quite considerably. Conclusions Several methodological processes and issues have been fundamental in forming management theory into its prevailing form. The demands of management theory as a science have, to a large degree, been satisfied initially through if-then statements, freedom from values, objectivity and falsifiability. The 1960s and 1970s were characterised by some specific developments, primarily the extension of the theory of the firm to encompass such considerations as multiproduct firms and long-term decision making. In the 1980s and 1990s, a further and radical revaluation in terms of information and motivation emerged. A broadening of theoretical paradigms has catered for these developments and a look at business journals illustrates various evolving trends which have enabled theory to keep pace with the times. In addition to the above, the issue of temporal validity requires that management theory fully accept and relate to some critical societal trends which are becoming increasingly more significant in the mid- to late 1990s. Such trends as globalisation, ecological consciousness and the increasing participation of women in the workforce are constantly and fundamentally altering the framework within which business-related writing operates. It is only through integrating such developments in an ongoing, consistent and comprehensive fashion that economic and management theory can retain its relevance and cogency in an ever mutating world. Furthermore, it is important that both writers and readers of such theory be aware of the nature and extent of these developments. If theory is not only to retain, but also increase its value, its extension, expansion and contemporary flavour need to be perceived and comprehended. By doing so, business writing will develop further its credibility in the scientific arena and beyond into society in the broader context. The developmental tendencies which have been listed relate to major societal problems, the resolution of which will take us well into the twenty-first century. Management theory in isolation cannot solve them. The issues are interdisciplinary and demand just such an approach. Management theory needs to work in conjunction with other sciences in order to develop viable Management as a science 153 JMH 6,3 solutions. To achieve this goal, work must proceed, as before, in accordance with the criteria of freedom from values, temporal and spatial generality, objectivity and falsifiability. Yet, these criteria must be imbued, if anything, more than before, with the spirit of the times and the impact of a very challenging and changing society. 154 Note 1. The first four approaches are discussed in Albach (1990, pp. 246-270). Coalition theory is examined by Herder-Dorneich (1992). The behavioural approach is well covered by Woehe in the same book edited by Albach (1990, pp. 270-91). The political-administrative approach is analysed by Drumm in the references given. Albach (1985) discussed the information-systems approach. The invisible-hand approach is found in Schneider (1984, p. 18) and the negotiation approach in Koch (1985). References Academy of Science (1993), Culture and Technical Innovation ± A Cross-Cultural Analysis and Policy Recommendations, Research Report 9, Berlin. Albach, H. (1959), Wirtschaftlichkeitsrechnung bei unsicheren Erwartungen, Cologne and Opladen. Albach, H. (1974), ``Innerbetriebliche Lenkpreise als Instrument dezentraler UnternehmensfuÈhrung'', Zeitschrift fuÈr betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, Vol. 26, pp. 216-42. Albach, H. (1985a), ``Hat die Allgemeine Betriebswirtschaftslehre eine Zukunftschance?'', in Forster, K.H. (Ed.), BeitraÈge zur Bankaufsicht, Bankbilanz und BankpruÈfung, papers in commemoration of Walter Scholz, 9-34, DuÈsseldorf. Albach, H. (1985b), ``Quo vadis Betriebswirtschaftslehre?'', in Ehrt, R. (Ed.), EinhundertfuÈnfzig Sitzungen betriebswirtschaftlicher Ausschuss des Verbandes der chemischen Industrie, Krefeld, 7 February, pp. 21-42. Albach, H. (1988), ``Kosten Transaktionen und externe Effekte im betrieblichen Rechnungswesen'', Zeitschrift fuÈr Betriebswirtschaft, Vol. 11, pp. 1307-36. Albach, H. (1989), Dienstleistungen in der modernen Industrie-gesellschaft: Perspektiven und Orientierungen, Publications Office of the Chancellor, Vol. 8, Munich. Albach, H. (1990), ``Business administration: history of the German speaking countries'', in Grochla, E. and Gaugler, E. (Eds), Handbook of German Business Management, SchaefferPoeschel, Stuttgart, pp. 246-70. Albach, H. (1992), ``Unternehmensethik: Konzepte-Grenzen-Perspektiven'', Zeitschrift fuÈr Betriebswirtschaft, ErgaÈnzungsheft 1. Albach, H. (1993), ``Betriebliches Umweltmanagement 1993'', Zeitschrift fuÈr Betriebswirtschaft, Special Supplement 1. Albach, H. and Witt, P. (Eds) (1992), Transformationprozesse in ehemals Volkseigenen Betrieben, Poeschel, Stuttgart. Anonymous (1997), ``Management by scenario'', Futurist, Vol. 31 No. 2, p. 48. Arrow, K. (1985), ``The economics of agency'' in Pratt, J. and Zeckhauser, R.J. (Eds), Principals and Agents: The Structure of Business, Boston, MA. Asgodom, S. (1993), Selbstmanagement fuÈr Frauen, Econ Verlag, DuÈsseldorf. Authenrieth, C., Chemnitzer, K. and Domsch, M. (1993), Personalauswahl und -entwicklung bei weiblichen FuÈhrungskraÈften, Frankfurt. Babbage, C. (1835), On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, London. Barrell, A. and Image, S. (1993), Executive Networking: Making the Most of Your Business Contacts, Director books, Hemel Hempstead. Bentner, A. and Peterson, S.J. (Eds) (1996), Neue Lernkultur in Organisationen: Personalentwicklung und Organisationsberatung mit Frauen, Campus Verlag. Beyer, N. and Beyer. G. (1996), Optimales Zeit Management, Econ Verlag, DuÈesseldorf. Biehel, F. (1994), Lean Service, Haupt, Bern. Bossle, L. and Kell, P. (Eds) (1995), Die Erneuerung der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft: Festschrift fuÈr Heinrich KuÈrpick zum 60, Bonifatius Geburtstag, Paderborn. Christ, P. and Neubauer, R. (1994), Kolonie im eigenem Land: Die Treuhand, Bonn und die Wirtschaftskatastrophe der fuÈnf neuen LaÈndern, Rowohlt, Reinbek. DeCrane, A.C. (1993), ``The ecological imperative for business'', Directors and Boards, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 4-6. Demmer, C. (Ed.) (1988), Frauen ins Management: Von der Reservearmee zur Begabungsreserve, Gabler, Wiesbaden. Domsch, M. (Ed.) (1993), Frauen auf dem Weg ins Management? ± Eine empirische Studie mit Hilfe einer Anzeigenanalyse (1990-1992), study conducted by the Institute of Personnel and Labour, Military University, Hamburg. Drumm, H.J. (1964), ``Die Zielsetzung der Erfahrungswissenschaft'' in Albert, H. (Ed.), Theorie und RealitaÈt, TuÈbingen, pp. 73-86. Drumm, H.J. (1993), ``Personalwirtschaft ± auf dem Weg zu einer theoretisch-empirischen Personalwirtschaftslehre'', in Hauschildt, J. and Gruen, O. (Eds), Empirical Research in Business ± Towards a Meaningful Management Theory, papers in honour of Eberhard Witte, Stuttgart. Edmonson, B. (1996), ``Work slowdown'', American Demographics, Vol. 18 No. 3, March, pp. 4-7. Fatemi, K. (1994), ``New realities in the global trading arena'', in Fatemi, K. and Salvatore, D. (Eds), The North American Free Trade Agreement, Pergamon, Oxford, pp. 3-12. Gutenberg, E. (1957), ``Betriebswirtschaftslehre als Wissenschaft'', University Speeches, No. 18, University of Cologne. Haggard, S. (1995), Developing Nations and the Politics of Global Integration, The Brookings Institution, Washington. Hauschildt, J. and Brockhoff, K. (1993), see contributions by the former on innovation management and those of the latter on techology management, in Hauschildt, J. and Gruen, O. (Eds), Empirical Research in Business ± Towards a Meaningful Management Theory, papers in Honour of Eberhard Witte, Stuttgart. Helleiner, G.K. (1990), The New Global Economy and the Developing Countries, Edward Elgar, Aldershot. È konomie zur Herder-Dorneich, P. (1992), ``Das Enternehmen als Koalition: Neue Politische O Betriebswirtschaftslehre'', in Materialien des Forschungsinstituts fuÈr Einkommenspolitik und Soziale Sicherheit an der UniversitaÈt KoÈln, Cologne. Hutmacher, M. (1996), ``Global sourcing: internationale arbeitsteilung, strategie fuÈr die zukunft'', Deutschland, No. 6, December, pp. 16-20. Kistner, K.P. and Steven, M. (1991), ``Management oÈkologischer Risiken in der Produktionsplanung'', Zeitschrift fuÈr Betriebswirtschaft, Vol. 11, pp. 1307-36. Kistner, K.P. and Steven, M. (1993), Produktionsplanung, 2nd ed., Heidelberg. Koch, H. (1985), Die Betriebswirtschaftslehre als Wissenschaft vom Handeln ± Die Handlungstheoretische Konzeption der mikrooÈkonomischen Analyse, TuÈbingen. Management as a science 155 JMH 6,3 156 Kreikebaum, H. (1990), ``Innovationsmanagement bei aktivem Umweltschutz in der chemischen Industrie'' in Wagner, G.R. (Ed.), Unternehmung und oÈkologische Umwelt, Munich. Kreikebaum, H. (1993), Umweltgerechte Produktion: Integrierter Umweltschutz als Aufgabe der UnternehmensfuÈhrung im Industriebetrieb, Gabler, Wiesbaden. Krelle, W. (1992), ``Ethik lohnt sich auch aÈkonomisch: uÈber die LoÈsung einer Klasse von Nichtnullsummenspielen'', in Albach, H. (Ed.), Unternehmensethik, Wiesbaden, Gabler, pp. 35-49. Kuhn, T. (1974), ``The structure of scientific revolution'', International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, Chicago, IL. Laux, H. (1979), Grundfragen der Organisation: Delegation, Anreiz und Kontrolle, Springer, Berlin. Laux, H. (1990), Risiko, Anreiz und Kontrolle ± Principal-Agent-Konzept ± EinfuÈhrung und Verbindung mit dem Delegation-Konzept, Heidelberg. Laux, H. and Liermann, F. (1987), ``Grundformen der Koordination in der Unternehmung: Die Tendenz zur Hierarchie'', Zeitschrift fuÈr betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung, Vol. 39, pp. 807-28. Luce, R.D. and Raiffa, H. (1957), Games and Decisions, Wiley, New York, NY. Luecke, W. (1991), ``Dispositiver Faktor Management: ein Vergleich'', Working Paper 2/91, Institut fuÈr betriebswirtschaftliche Produktions- und Investitionsforschung, University of GoÈttingen. McKenna, R. (1991), Relationship Marketing, Addison-Wesley, Chicago, IL. March, J.G. and Simon, H.A. (1958), Organizations, Wiley, New York, NY. Markley, O.W. (1996), ``Global consciousness: an alternative future of choice'', Futures, Vol. 28 No. 6-7, August/September, pp. 622-6. Marschak, J. and Radner, T. (1972), Economic Theory of Teams, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT and London. Martin, H. and Schumann. H. (1996), Die Globalisierungsfalle, Reinbek bei Hamburg, Rowohlt. Mayer, K.U., Allmendinger, J. and Huinink, J. (Eds) (1991), Vom Regen in die Traufe: Frauen zwischen Beruf und Familie, Frankfurt. Meffert, H. and Kirchgeorg, M. (1997), Marktorientiertes Umweltmanagement: Grundlagen und Fallstudien, 3rd ed., Schaeffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart. Murphy, C.N. and Tooze. R. (Eds) (1991), The New International Political Economy, Lynne Rienner Publishers, Boulder, CO. Myers, G. (1996), ``Selling (a man's world) to women'', American Demographics, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 38-9. Naisbitt, J. (1994), Global Paradox, William Morrow and Company, New York, NY. O'Brian, R. (1992), Global Financial Integration: The End of Geography, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, London. È ko-Audit: Umweltmanagement und UmweltbetriebspruÈfung nach der EG-Verordnung 1836/93 O (1995) Blottner, Taunusstein. Ohmae, K. (1995), The End of the Nation State, The Free Press, New York, NY. Passau (1994), Scientific Convention of the Universities Association for Management Education. Patrickson, M. (1994), ``Workplace management strategies for a new millennium'', International Journal of Career Management, Vol. 6 No. 2, pp. 25-32. Popper, K. (1935), Die Logik der Forschung, Vienna. Reese, J. (1993), ``Is lean production really lean?'', in Fandal, G., Guttledge, T. and Jones, A. (Eds), Operations Research in Production Planning and Control, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, pp. 49-70. Rehkugler, H. and Voigt, M. (1990), ``Unternehmerinnen, 10 Thesen zu einer von der Wissenschaft vernachlaÈssigten Personengruppe'', Die Betriebswirtschaft, pp. 353-63. Reiter, S. (1985), Report of the Working Group on Markets and Organizations, National Research Council, Evanston, IL. Sarkis, J. (1995), ``Manufacturing strategy and environmental consciousness'', Technovation, Vol. 15 No. 2, March, pp. 79-97. Schauenberg, B. (1991), ``Organisationsprobleme bei dauerhafter cooperation'', in Ordelheide, D., Rudolf, B. and BuÈsselmann, E. (Eds), Betriebswirtschaftliche und oÈkonomische Theorie, Schaeffer-Poeschel, Stuttgart, p. 329. È ko-Audit + O È ko-Controlling: Neue Schimmelpfeng, L.D. and Machmer, D. (Eds) (1995), O Erfahrungen und LoÈsungen aus der Anwendungspraxis, Blottner, Taunusstein. Schneider, D. (1990), ```Unsichtbare Hand' ± ErklaÈrungen fuÈr die Institution Unternehmung'', in Streim, H. (Ed.), Ansprachen. Schreyoegg, G. (1994), Umwelt, Technologie und Organisationsstruktur, Haupt, Bern. Schueler, W. (1978), ``Teamtheorie als Komponente betriebswirtschaftlicher Organisationtheorie'', Zeitschrift fuÈr Betriebswirtschaft, Vol. 48, pp. 343-55. Sietz, M. (Ed.) (1994), Umweltbewusstes Management, 2nd ed., Taunnusstein, Blottner. Simon, H. (1981), Entscheidungsverhalten in Organisationen, Munich. Simon, H. (1989), ``Die Zeit als strategischer Erfolgsfaktor'', in Zeitschrift fuer Betriebswirtschaft, pp. 70-93. Stadermann, H. (1996), Weltwirtschaft, 2nd ed., Ullstein, Frankfurt. Stevens, C. (1994), ``The greening of trade'', OECD Observer, No. 187, April/May, pp. 32-4. Sturm, N. (1997), ``Falsche hoffnung'', SuÈddeutsche Zeitung, 21 May, (Internet). Wildemann, H. (1988), Das Just-In-Time-Konzept: Produktion and Zulieferung auf Abruf, TCW, Frankfurt. Wuertele, G. (Ed.) (1995), Agenda fuÈr das 21. Jahrhundert: Politik und Wirtschaft auf dem Weg in eine neue Zeit, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurt. Zinn, K.G. (1992), Soziale Marktwirtschaft, B.I. Taschenbuch Verlag, Mannheim. Management as a science 157