OPTIONS FOR REVISING THE CHILD CREDIT Abstract

advertisement

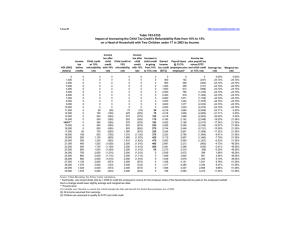

OPTIONS FOR REVISING THE CHILD CREDIT Frank Sammartino, C. Eugene Steuerle, and Adam Carasso The Urban Institute May 3, 2001 Abstract President George W. Bush, as part of his tax reform package, proposed to double the child credit from $500 to $1,000 and create a new ten percent tax bracket. Together, these provisions would reduce the marginal tax rates paid by low-income families. This paper examines the President’s proposal and other proposals circulating in Congress in early May 2001. Five types of analyses are provided: the extent to which benefits for raising children vary at different income levels, the marginal tax rates implicit in various proposals, the effect of the proposals on marriage penalties, their distributional effects, and, finally, the associated revenue cost. The authors would like to thank the Annie E. Casey Foundation for their support of this project. All opinions, errors, or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. 2 OPTIONS FOR REVISING THE CHILD CREDIT Among the provisions put forward by President Bush as part of his tax reform package was an increase in the child credit from $500 to $1,000. In addition, he proposed dropping the rate of tax paid on the first dollars of taxable income from 15 percent to 10 percent. Together these provisions successfully reduce the marginal tax rates paid by lower income individuals—especially as the amount of their earned income tax credit (EITC) declines with increased earnings. For a number of years, researchers have been concerned with the high marginal rates faced by lower income individuals. These high rates tend to penalize additional work, as well as marriage. Accordingly, several proposals have been made to enhance the child credit or design it in such a way that these disincentives were reduced or removed. Of course, many proposals also had concern for providing additional supplements for low-income households—goals that sometimes coincided with, sometimes did not, the removal of work and marriage disincentives. In 2001, some of the debate on child-related provisions also centered on simplification. Examples include the common definition of a qualifying child, as suggested by the Joint Committee on Taxation, and a more uniform credit that would combine the child credit, the dependent exemption and the earned income tax credit. At this stage, however, many of these broader simplification and integration ideas have been deferred. Attention is focused more narrowly on possible modifications to the child credit proposal put forward by the President—modifications that are in keeping with his goals of avoiding high marginal rates for low-income individuals. Note the special concern with families in the $10,000 to $25,000 income range. While few of these have much in the way of traditional welfare benefits under Temporary Assistance to Needy Families or TANF (their income is already too high to get many benefits), they are subject to the phase out of eligibility for Food Stamps, housing vouchers and other housing benefits, as well as the loss in eligibility for Medicaid. While we do not specifically examine these non-tax programs in this paper, this is a prime consideration when looking at the tax rates from the tax programs. Because of the work and marriage penalties associated with these high rates, this suggests not letting their income tax rates start—or keeping them very low—until benefits from other programs have phased out. Indeed, this consideration was a prime motivation behind the way that the Administration proposed an expanded child credit and a 10 percent rate bracket. These provisions were designed in such a way under the President’s proposal that for the most part, the EITC phase out would be over by the time that the positive income tax rates came into place. This paper mainly concentrates on provisions that would involve modest extensions of the President’s plan and plans actively being considered in Congress in early May 2001. Five types of analyses are provided: the extent to which benefits for raising children vary at different income levels, the marginal tax rates implicit in various 3 proposals, the effect of the proposals on marriage penalties, their distributional effects, and, finally, the associated revenue cost. In several cases, the revenue cost is modest relative to the cost of the tax bill and even relative to the cost of expanding the child credit. Nonetheless, assuming that there is a fixed budget for a tax package, we also examine some proposals that raise back modest revenues as a means of demonstrating the types of adjustments that might be required to keep the total package within a fixed budgetary goal. The options considered here will be the following: Current Law The President’s Proposal The House Bill (as of May 4, 2001) A “13-15” Proposal A “10-7” Proposal Slower EITC phase out “13-15” with a smaller 10 percent bracket “13-15” with a top rate of 35 percent A more precise explanation of their provisions are contained in the following table. The Tax Benefits Available to Families Raising Children Under current law, the benefits available to families raising children vary considerably according to the family’s income level (see figures). For instance, a twoadult, two-child, family phases into the full earned income tax credit at $10,020 and then phases out of it as family income exceeds $13,090. A single head of household is given an extra standard deduction and a different rate schedule for raising children. The dependent exemption is made available to households who provide support to children, as is a child credit. Both the dependent exemption and the child credit are phased out at higher income levels. The net effect of these proposals ends up creating differing levels of benefits—a u-shaped pattern identified in previous literature. The figures here demonstrate that this u-shape is flattened considerably by almost all proposals, whether that of the President or the House bill. Especially good in this regard is the “13-15” proposal. 4 SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS EXAMINED Current Law: includes a non-refundable $500 child credit for households with fewer than 3 children; for households with more than 3 children, allows refundability of the child credit up to the excess of social security tax (employee portion only) over EITC. The President’s Proposal: doubles the $500 child credit; extends the phase-out range to higher income levels; changes tax rates, including a 10 percent bracket for the first dollars of taxable income ($6,000 for a single return, $10,000 for a head of household return, and $12,000 for a joint return). The House Bill: adopts the President’s proposal for the most part, but does not extend the phase-out range of the child credit; extends current law refundability of the child credit to all families with children. A “13-15” Proposal: Same as the House Bill, except drops the refundability of the child credit according to the excess of Social Security taxes paid over the EITC and substitutes a refundable credit up to 15 percent of the excess of earnings over the beginning phase out point of the Earned Income Tax Credit ($13,090). A “10-7” Proposal: Same as the “13-15” proposal, but begins phasing in the refundable child credit at the point at which a maximum credit is received for a two-child household ($10,020), and phases in the credit only at a 7 percent rate. Slower EITC Phase out: Same as the House Bill, but drops entirely any refundability for the child credit and substitutes a phase out of the EITC at 15 percent for joint returns and 11 percent for heads of household. “13-15” with a Smaller 10 Percent Bracket: Same as the “13-15” proposal, but raises some revenues back by reducing the width of the 10 percent tax bracket from $6,000, $10,000, and $12,000 by 10 percent to $5,400, $9,000, and $10,800 respectively for singles, heads of household, and joint returns. “13-15” with a top rate of 35 Percent: Same as the “13-15” proposal, but assumes a top rate of 35 percent instead of 33 percent. 5 Marginal Tax Rates The second set of graphs presented here show marginal tax rates for several proposals. As can be seen, the President’s proposal succeeds in reducing marginal tax rates to 21 percent or lower for most people with either low or moderate incomes. Many of the other proposals tend to reduce them even lower for those in the income ranges above $10,000 or $13,000. In the case of the refundable child credit proposals, this reduction in rates does require that marginal rates rise eventually at higher income levels. The general goal is to reduce the income tax rates most where other programs are phasing out. The House bill ends up with a set of rates that bounce around considerably. This is due to the nature of the refundable child credit. It turns out that refundability here works its way in rather quickly. An additional dollar of earnings eventually generates less earned income tax credit and perhaps more tentative income tax, but the credit quickly offsets this amount, and then the credit also offsets Social Security tax—yielding an effective marginal income tax rate of a negative 7.65 (or –7.65) percent in a given range. Marriage Penalties When the tax benefits are fairly level as income increases, this has an additional advantage. It tends to reduce marriage penalties. Many of these penalties arise because benefits available, say, to a head of household, are lost when that person marries a single person who has earnings. The additional earnings add to household income, thus leading to a phase-out of those benefits. The enclosed tables show that almost all proposals reduce marriage penalties significantly by cutting back on this rate of phase-out one way or the other. Distributional Effects Generally speaking, there are only modest distributional differences among the bills considered here. The percentage of tax paid by those in higher income brackets, for instance, remains high and changes little. Nonetheless, refundability at lower income levels does distribute some amount of tax reduction (or, more precisely, outlays for the refundable portions of the tax cut) further down the income scale. Note that narrowing a bit the length of the 10 percent rate bracket has only a very slight effect at all income levels despite its ability essentially to pay for refundability of a proposal such as “13-15.” For many taxpayers, its effect is inframarginal: in economic terms, it has no effect on the marginal tax rate they pay on additional dollars earned—and is, therefore, less likely to affect economic incentives. On the other hand, adopting a smaller cut in the top rate has a very large marginal effect because as the highest rate of tax, it is the marginal rate for all taxpayers who fall in that tax bracket. 6 Revenue Effects Revenue effects are also shown in the attached tables. Note that the cost of many of the provisions added to the House bill are small relative to the whole package. When it comes to paying for provisions, the slight narrowing of the 10 percent bracket roughly pays for the adoption of the “13-15 proposal” over and above the cost of the House bill, while even a 2 percentage point increase in the top rate more than pays for any of these types of proposals. We are not advocating any of these provisions but merely showing the relative size of their impact. (Note, however, that our revenue estimates are for a given year based on data in the late 1990s; changes in incomes since then and the indexing of various provisions, among other factors, will give a different result for the 10-year period shown with official revenue estimates presented by the Joint Committee on Taxation.) Conclusion Concern over marginal tax rates paid by low and moderate-income taxpayers can be accommodated at modest cost in a tax bill such as is being considered in 2001. A variety of different options can be considered which essentially take off from the President’s plan by placing emphasis on getting more help to low-income working families with children, while reducing their high marginal tax rates and removing some of the marriage penalties they face.