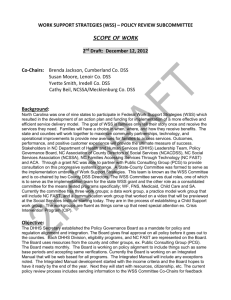

Early Lessons from the Work Support Strategies Initiative: Planning and Piloting

advertisement