Document 14590304

advertisement

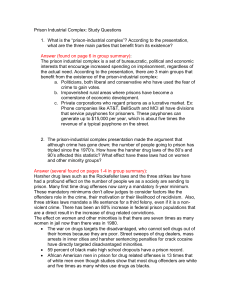

A BRIEF FROM THE CHARLES COLSON TASK FORCE ON FEDERAL CORRECTIONS: MARCH 2015 Drivers of Growth in the Federal Prison Population The federal prison population has grown by 750 percent since 1980, resulting in rapidly increasing expenditures for 1 incarceration and dangerous overcrowding. In response, Congress created the Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections to examine trends in correctional growth and develop practical, data-driven policy responses. 2 Following the example of many states that have recently engaged in criminal justice reform, the first step for the Task Force is to understand the underlying drivers of growth in the prison population. Number of Drug Offenders More than Doubled in Past 20 Years The biggest driver of growth in the prison population is in federally sentenced drug offenders, almost all of whom 3 were convicted of drug trafficking. In fiscal year (FY) 2013, there were almost 50,000 more drug offenders in federal prisons than there were in FY 1994. Incarceration for drug offenses disproportionately affects nonwhite offenders: in FY 2013, over 75 percent of all drug offenders in federal prison were black or Hispanic. Federally Sentenced Drug Offenders Drove Growth in Prison Population 1994 100,000 2013 80,000 Almost 50,000 more drug offenders in federal prison than in FY 1994 60,000 40,000 20,000 0 Violent Property Public-Order Supervision Sex Weapon Immigration Drug Source: Urban Institute analysis of FY 1994 and FY 2013 Bureau of Prisons data. The Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections was created by Congress. This nine-person, bipartisan, blue-ribbon task force is mandated to examine challenges in the federal corrections system and develop practical, data-driven policy responses. The Task Force will meet throughout 2015 to conduct its work and present its findings and recommendations at the end of 2015 to Congress, the Department of Justice, and the President. The Urban Institute and the Center for Effective Public Policy provide research and logistical support to the Charles Colson Task Force. This brief was developed by Samuel Taxy, research associate at the Urban Institute. Drug Offenders More Likely to Go to Prison, Serving Lengthy Sentences The population growth is driven by both the number of people who are admitted to prison for drug crimes every year and the length of their sentences. In FY 2013, more people were admitted to federal prison for drug crimes than any other crime type, and the average sentence for those entering prison was almost six years. Every year, about 95 4 percent of federally sentenced drug offenders receive a term of incarceration as part of their sentence, up from about 76 percent in the year before the passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act in 1986, which established mandatory minimum penalties for certain drug offenses. 5 In particular, length of stay for drug offenders, often dictated by statutory mandatory minimum penalties, has driven most of the recent growth. Though the number of admissions has remained largely constant over time, the number of drug offenders in federal prison has increased because of people serving longer sentences. Length of stay for drug offenses, a key driver of growth in the federal prison population, is partly determined by characteristics of the current offense and relevant criminal history information. For drug offenders in federal prison at the end of FY 2013, 120,000 100,000 Drug offenders in prison 80,000 the average sentence was 11 years, and almost all will serve at least 87 percent of the sentence; three in five were sentenced pursuant to a statutory mandatory minimum penalty for drug trafficking; one in three were in the lowest criminal history category at time of sentencing; and one in four sentences for drug offenses explicitly accounted for weapon involvement. 60,000 40,000 Drug offender admissions 20,000 0 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 6 Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics Federal Criminal Case Processing Statistics, FY 1998-2012. Notes 1. Julie Samuels, Nancy La Vigne, and Samuel Taxy, Stemming the Tide: Strategies to Reduce the Growth and Cut the Cost of the Federal Prison System (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2013); Nancy La Vigne and Julie Samuels, “The Growth and Increasing Cost of the Federal Prison System: Drivers and Potential Solutions” (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2012); and Nathan James, “The Federal Prison Population Buildup: Overview, Policy Changes, Issues, and Options” (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2013). 2. Nancy La Vigne, Samuel Bieler, Lindsey Cramer, Helen Ho, Cybele Kotonias, Deborah Mayer, David McClure, Laura Pacifici, Erika Parks, Bryce Peterson, and Julie Samuels, Justice Reinvestment Initiative State Assessment Report (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, 2014). 3. Offense categorization is based on the Bureau of Prisons’ determination of most serious offense. At the end of FY 2013, over 99 percent of drug offenders in federal prison were convicted of drug trafficking. The source of all data presented herein (unless otherwise noted) is Urban Institute analysis of data provided by the Bureau of Prisons and US Sentencing Commission, FY 1994–FY 2013. 4. USSC (United States Sentencing Commission), Sourcebook of Federal Sentencing Statistics (Washington, DC: USSC, 2004–14). 5. Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Federal Offenses and Offenders: Sentencing and Time Served” (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, 1987). 6. Includes only those sentenced FY 1998–2013. This project was supported by Grant No. 2014-ZR-BX-K001 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice's Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the US Department of Justice or the views of the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or influence scholars’ conclusions.