Pre-Enlightenment England

advertisement

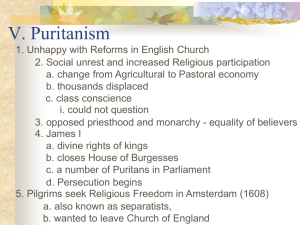

Pre-Enlightenment England While continental European states were developing absolute and centralized monarchies, England, in a chaotic and violent century, radically reduced the power of the monarch and developed an alternative state in which the powers of the monarch became subsidiary to the power of the branches of government. The political experiments of England would be dramatic, from absolutist tendencies at the beginning of the century, to the overthrow of the monarch in the middle of the century and the development of an English Republic, and finally to the restoration of the monarch and the severe limitation of monarchical powers. These titanic changes were largely driven by religious concerns as the issues of monarchy in England collided with the concerns and complaints of an increasingly large and increasingly radical Protestant minority. James I When James I (1603-1625) succeeded Elizabeth I in 1603 he became the first foreign monarch of modern England. He was the king of Scotland, James VI, and was the son of Mary, the Queen of Scots; he was, therefore, the next in line to be king when Elizabeth died. James became king at an especially difficult time to become King of England. The government was deeply in debt, the English Church was divided while a radical Protestant minority was growing, and the Parliament was not happy with the power that had been accruing to the monarch over the past several decades. James's problem was that he could not pay his bills without the approval of Parliament, for English law forbade the king from raising revenues independently of the consent of Parliament. James, however, had debts to pay and an extravagant lifestyle to keep up. So he argued that he had some privileges to raise money through customs duties; these duties, called impositions, lit the fire beneath Parliament's feet and the subsequent history of James's reign is a long, protracted battle with Parliament over the powers of the king. The church was an even bigger mess. The English church was dividing into a conservative camp that wanted to retain the religious ceremonies and the hierarchy of the church and a radical, Calvinist camp called Puritans who wanted to "purify" the church of everything not contained in the Old and New Testaments. The Puritans demanded that the English church abandon the elaborate ceremonies and flatten the hierarchy of the church into something more closely resembling the voluntary associations of the Calvinist church. James, however, would have none of the Puritan argument and declared, in 1604, that he was fully in the camp of the religious conservatives. This division between the monarch and the Puritans, which would be continued by his son, Charles I, lit the fire that ignited the English Civil War. Charles I James was followed by his son Charles I, who ruled England from 1625 until his execution in 1649. Like James, Charles was chronically short of money. While James lived extravagantly, the extravagance of Charles put his father to shame. In addition, Charles was prosecuting a war against France and bungling it, but he still needed money. Since Parliament would not increase his funds through taxation and tariffs, Charles went about creatively raising money of his own. In 1628, Parliament met and drafted the Petition of Right in which it declared several important rights of individuals and Parliament that severely curtailed the power of the monarch: No funds could be borrowed or raised through taxes and tariffs without the explicit approval of Parliament; No free person (Britain had slavery at the time) could be imprisoned without a reason; No troops could be garrisoned in a private home without permission. (This petition of right would later become the basis of both the English Constitution and the American Revolution). Parliament voted funds for Charles to prosecute his war with France under one condition: he had to sign the Petition of Right and so agree to its terms. This he did, but he probably never intended to keep his word. In fact, Charles immediately broke his promise and, to avoid confrontation with Parliament, he dissolved it and refused to call it again until 1640. Now he had to make his way alone, without funds from Parliament. So Charles instituted the first major budget cuts in the history of the modern state: he made peace with his enemies since, after all, peace is cheaper than war; he downsized the government administration, and he became extremely innovative in the raising of taxes. He did this by enforcing laws that had fused unused for decades or centuries and he applied existing tax laws to areas that were never covered by them. Charles had one and only one goal: to rule England without Parliament, in other words, to rule England as an absolute monarch. And, in the words of Guido da Montefeltro, it almost worked. Charles, however, did not have a large or strong standing army that was centralized and loyal to the king, nor did he have a civil bureaucracy trained or efficient in centralized government. Still, however, he might have made it work if it weren't for religion. Like his father, Charles sided with the religious conservatives against the more radical Puritans. The archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, was particularly hostile to the Puritans' complaints and Charles allowed him to freely take any measures to stifle their dissent. In 1633, Charles forbade Puritans from publishing or preaching, and in 1637, they tried to bring Scotland under the fold of the English church. The Scots had, for a long time, a Calvinist church based on a flattened hierarchy and the purification of the religion of all non-Biblical practices. The imposition of the English church--which included the English prayerbook, church hierarchy, and rituals and sacraments that were derived from Catholic ceremony--was too much for the Scots to take. So they rebelled. War, as you remember, is not cheap, and Charles was forced to reconvene Parliament in 1640 in order to fund the repression of the Scots. During the twelve years that Parliament did not meet, its members had been stewing in their juices and were loaded for bear. When they met in April of 1640, they refused to grant Charles any money at all until he had adequately redressed the long, long list of complaints that they brought with them. Charles, naturally, refused and dismissed them in May of 1640; hence the title, "The Short Parliament." This, however, was not a working strategy, so he reconvened Parliament and finally agreed to their terms. The Parliament set to work with ruthless efficiency when it reconvened in November. Raising taxes without Parliament approval was made illegal; William Laud, the archbishop of Canterbury, was impeached and executed; the primary instruments of Charles' centralized bureaucracy were abolished; and finally, Parliament passed a law that allowed Parliament and Parliament alone to dismiss itself in addition, it made it law that Parliament had to meet at least every three years. Charles went along with these measures, but when rebellion broke out in Ireland, radicals in Parliament proposed a bold move. Charles was asking for troops to send to Ireland, but the radicals didn't believe that Charles could be trusted with an army. So they proposed that the army be directly under Parliament's control. This, however, was too much for Charles to bear, so he invaded Parliament with his army. This move, bold and foolish at the same time, inspired Parliament to issue the Militia Ordinance, which declared the army under Parliamentary control. Thus began the English Civil War. The English Civil War (1642-1646) The English Civil War started as a conflict between Parliament and Charles over constitutional issues; it fired its way to its conclusion through the growing religious division in England. The monarch was supported by the aristocracy, landowners, and by the adherents of the Anglican "high church," which retained the ceremonies and hierarchy so despised by the Puritans. The Parliamentary cause was supported by the middle class, the Puritans, and the radical Protestants. The king's forces roundly beat the Parliamentary forces for almost two years and the Parliamentary cause seemed all but lost. In 1642, however, Parliament reorganized its army under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell, who was a landowner and, in religious matters, an Independent. The Independents believed that each congregation and each region should be free to decide what ecclesiastical structure it would adhere to. If a congregation wished to be Puritan, so be it; if it wished to be Anglican, that's fine, too. Cromwell called his army "The New Model Army,” and in 1644, he turned the tide of the war. In 1645, the Parliamentary Army thoroughly defeated the royal army and in 1646, Charles surrendered. He did not, however, lose his crown. Parliament was now calling all the shots, but Charles, in name at least, was still king of England. He did not, however, wish to maintain this situation. After several years of trying to recapture power, Charles was finally arrested by Parliament, tried for treason, and executed. It's impossible to describe how revolutionary this action was. Parliament had declared itself supreme over the king, who, in European political theory, ruled by the election of God. If something or someone is supreme over the king, why should a people need a king? This was frightening new territory. When Charles was publicly executed, the gathered masses remained absolutely mute. Executions were normally raucous and festive affairs, full of shouting and laughing and whooping, but the execution of the king was too hard to take. No one said a word and many wept openly. They were experiencing the first great shock of a brave new world. The Puritan Republic Before the execution of the king, Parliament dissolved the institution of the English monarchy, the aristocracy, and the Anglican Church. They were led in this revolution by Cromwell himself. When the king had been defeated, Parliament was largely made up of Calvinist Presbyterians. The Presbyterians wanted to abolish certain rituals and the current church hierarchy, but they also wanted to set up a new hierarchy of church officials called "presbyters." At the conclusion of the civil war, this Parliament wanted to abolish the Anglican Church and impose Calvinist Presbyterianism on all of England and Scotland. Both the Puritan and Independent minorities balked at this suggestion and demanded a religious tolerance of all forms of Protestantism; when they were rebuked, Cromwell and the Puritans ejected all the Presbyterians by force and took over Parliament. It was Cromwell's new parliament that executed the king and formed a new, republican government. They now called England, which had previously been a kingdom, a "commonwealth." It was to be run by Parliament, which would not only legislate and raise taxes, but would also perform the duties traditionally reserved for the monarch, such as running the judiciary and heading the army. The real power, however, was Oliver Cromwell. He had the army. He eventually tired of the arguments and the corruption in Parliament, and dispersed it by force in 1653. Thus ended the English commonwealth. The new state Cromwell set up he called the "Protectorate," and the officers of his army drafted a new constitution for this unique institution. Cromwell, as "Lord Protector," served as a dictator. The Lord Protectorship was made a hereditary office, and in 1655, Cromwell dismissed Parliament permanently. For all practical purposes, Cromwell had made himself absolute monarch over England, an achievement that James I and Charles I could only dream of. Cromwell was above everything else a brilliant and determined general. During the period of his rule, he conquered both Ireland and Scotland. England thus became an empire: Great Britain. But life in the new Puritan Republic was hard. The Puritans set about reforming the entire moral life of the English. They abolished any public recreation on Sunday, which was the only day off anyone ever got, and they passed restrictive laws on English behavior. For all practical purposes, the English were living under a Puritan king. Life under a monarch was a living memory, and when Cromwell died in 1658, he was succeeded by his weak and less brilliant son. Faced with a Puritan dictator or an Anglican king, the English opted for the latter. In 1660, a dissenting general reconvened Parliament, which then restored the English king, the aristocracy, and the Anglican Church. The grand experiment in republicanism had failed in the most tawdry autocracy. Charles II Charles II, the son of Charles I, was restored to the monarchy in 1660 and ruled until 1685; this period in English history is called, logically enough, the "Restoration." On the surface, at least, the restoration meant a return to the England of 1642. Charles, however, was an Anglican in appearance but Catholic in sympathies, for he had spent a large part of his life living in France. His brother James, the next in line to the throne of England, had converted openly to Catholicism and the English deeply distrusted Charles' intentions. No matter what Charles' intentions, he believed ardently in religious tolerance for both Catholics and Protestant minorities. In 1672, he issued the Declaration of Indulgence, which granted religious freedom to all Catholics and all Protestants. He did this in part to convince Louis XIV to agree to an alliance with him against the Dutch, but Parliament, made up mostly of Anglicans, refused to finance the war unless Charles revoked the Declaration, which he did. Parliament followed this victory by issuing the Test Act. This law required all military and civil officials to renounce the doctrine of transubstantiation (a doctrine that is fundamental to the Catholic Eucharist); in part, this law was meant to prevent the accession of the Catholic James to the throne. James II It didn't work. When Charles died in 1685, James became king and ruled until 1688. As a Catholic, his first action was to insist that the Test Act be revoked. Parliament refused and James, like Charles I before him, dissolved Parliament when he couldn't get his way. He then displayed his opposition to the Test Act by appointing openly Catholic civil and military officials and in 1687; he declared all religious tests to be null and void. Years ahead of his time, he declared religious tolerance to be national policy and, in an affront that few could bear, he arrested Anglican bishops who refused to spread the news about the new religious policies. While the English were stewing in their juices over all these changes, no one really did anything about it. They were hoping that James would die and the throne would revert to his sister Mary, who was Protestant. However, in 1688, James and his Catholic wife had a son. The heir to the English throne, then, was Catholic, and this dashed everyone's hopes. England, it appeared, would soon revert to a Catholic state. The Glorious Revolution (1688) The major parties that made up Parliament flew into action. Both the supporters of Parliament (Whigs) and the supporters of the monarch (Tories) agreed that a Catholic line of kings was intolerable, so they voted to ask William of Orange, the duke who was married to James's sister Mary, to invade England. This was a bizarre turn of events. Essentially, Parliament was voting out one king and voting in another; this was a dramatically different way of doing state business. William of Orange raised an army and landed on English soil in November of 1688. Not only did no one oppose him, the English welcomed him with open arms. He had, after all, been invited to invade England and assume the monarchy. James, seeing that he had no support, quickly fled to France and the protection of Louis XIV. With the king having hightailed it out of England, Parliament declared the throne vacant and declared William and Mary to be the sovereigns of England in 1689. Because the king had been deposed by an act of Parliament without any bloodshed whatsoever, the English called this the "Glorious Revolution." Parliament drew up a Bill of Rights, which William and Mary agreed to. This Bill of Rights severely restricted the power of the monarch over Parliament and over individuals and would become the fundamental basis of the American Bill of Rights over a century later. Included in the English Bill of Rights were many elements of the early Petition of Right with some notable additions: No monarch could assume the throne without the express approval of Parliament; The monarch would be subject to all the laws of the realm; No Catholic could assume the English throne. The Glorious Revolution and the English Bill of Rights are two of the most astonishing and farreaching events of the modern period. From them were planted the seeds of the American Revolution and the American constitution and ultimately, the fundamental structure of all modern government: representation and checks and balances. For the government that the English slowly forged after the Glorious Revolution was one in which the branches of government were independent of one another. The executive branch, headed by the monarch, was subject to the authority of the legislative branch, the Parliament, which was dependent on the executive power of the monarch. The judiciary functioned independently of both Parliament and the king. After a century of uncertainty and violence, the English solution was to limit the powers of all branches of government to prevent any one branch from exerting excessive influence. The news wasn't all bad for religious minorities, though. In 1689, Parliament passed the Toleration Act, which allowed Catholics and minority Protestants to freely practice their religion.