Volume XXIV Number 2 2006

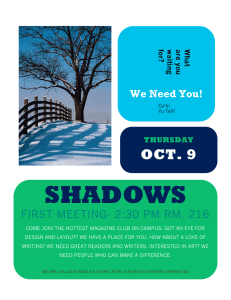

advertisement