Document 14545442

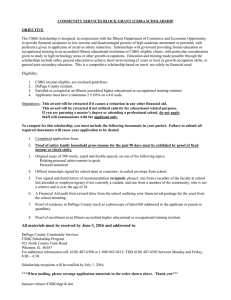

advertisement