Housing security in tHe WasHington region

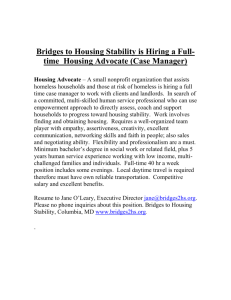

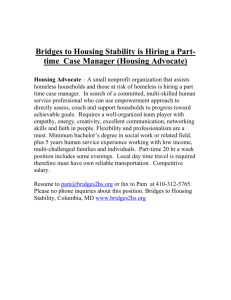

advertisement