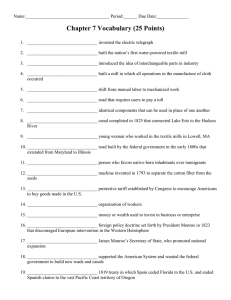

American Biography – John C. Calhoun (1782 – 1850)

advertisement

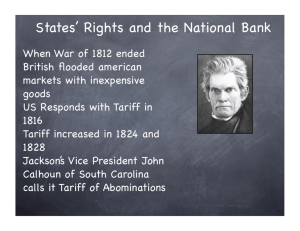

American Biography – John C. Calhoun (1782 – 1850) John was born on this father’s farm in the hillside country of South Carolina. His father owned a few slaves and was a local political leader. John was a first generation American as his parents had emigrated from Ireland. His early schooling was very limited. He was largely self-educated. However, after he was 18, he spent two years being taught by his brother-in-law, Reverend Moses Waddel, in a “log college”. At 20, John entered Yale University. He graduated with distinction in 1804. He studied law in Charleston, South Carolina and, after finishing his studies at a law school in Connecticut, he began practicing in his home state (1807). In 1808 and 1809 he was elected to the legislature of South Carolina. He took part in the development of a constitutional compromise in the state. Within the state there existed two distinct regions, the hill country (in the north) and the low-country (in the south). The farmers of the hill-country had smaller farms, while the low-country was dotted by large plantations. There were also more people in the southern than in the northern part of the state. To satisfy the interests of both groups, it was agreed that the government of the state should be based on “concurrent” rather than “numerical” majorities. This meant that there had to be majorities in both regions to have legislation passed rather than a simple majority for the entire state. In 1811, John married his cousin, Floride Bonneau Calhoun, the daughter of a wealthy plantation owner. John now became a member of “southern aristocracy”. His economic future was secure. In that same year, he entered the House of Representatives. John’s political influence continued to rise. In 1817-1825, he was the Secretary of War in the cabinet of James Monroe. In 1824, he was elected Vice-President to John Quincy Adams. However, John soon realized that Andrew Jackson would probably be elected president in 1828, so he deserted Adams and began to support Jackson. Indeed, in 1828, Jackson was overwhelmingly elected president – with John as his Vice-President! However, relations between Calhoun and Jackson soon broke down. Finally, the issue of a high protective tariff, the “Tariff of Abomination”, drove the two men apart. John wrote several documents (“Exposition and Protest”, 1828 and the “Fort Hill Letter”, 1831) in which he argued that the Union was based on a compact between the states. Therefore, the states still retained the right to judge on the constitutionality of acts passed by the federal government. If they believed that an act went beyond the powers of the federal government, the states could declare it illegal within their state boundary. In 1832, South Carolina declared the tariff null and void within its state. President Jackson responded to these developments as if he were engaged in a duel. He threatened to arrest John. In response, John resigned as Vice-President and returned to his home state. In the next year, John was elected to the Senate by South Carolina. Over the next seventeen years he became the most vigorous and outspoken spokesperson on behalf of states’ rights, the protection and expansion of slavery, and agricultural interests. He wrote several books during these years in which he argued that liberty and equality were incompatible because by forcing all men to be equal, their individualism would be destroyed. He also suggested that the principle of concurrent majorities should be applied to national politics to safeguard the interests of the South as well as those of the North. In practical terms, he believed that there should be two Presidents, one representing the South, the other the North, each with a veto. During these years as well, John was instrumental in establishing a new political party in opposition to the party of Andrew Jackson. The party was called the Whigs. In 1840, the Whigs were able to elect General Harrison as President. (However, he died one month later and succeeded by his Vice-President, John Tyler, a former Democrat). In 1844, John was appointed Secretary of State by President Tyler. In this position, he was responsible for securing the entry of Texas into the Union in 1845. Later in the year he returned to the Senate where he played a leading role in fashioning the tariff of 1846. Calhoun opposed the war against Mexico, the Wilmot Proviso, and the entry of California into the Union. The reason for his opposition was the same in all cases – he believed that the rights of the slave states were threatened. He was convinced that there was no hope for political equality between the North and the South. He was convinced that the Compromise of 1850 was a waste of time. The debate over the Compromise had worn him out. His last speech to the Senate had to be read by another senator because he was too weak to speak. He warned that the “dissolution of the Union is the heaviest blow that can be struck at civilization and representative government”. To prevent that from happening, he recommended that a sectional veto should be added to the Constitution, even if that meant the establishment of a dual presidency. He died a month later. John was the spokesperson and philosopher of the South. He laid the political foundations for the southern “lost cause” in defense of slavery, states’ rights, and protection of agriculture, especially southern crops like cotton and tobacco. Eleven years after his death, the South seceded from the Union. It justified its action on the basis of the arguments that John had advanced. Question for thought: Using Calhoun’s biography and information from the text, assess his role in the political and social development of the United States during the almost fifty years of his involvement.