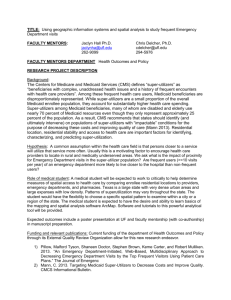

Risk-Based Managed Care in New Hampshire’s Medicaid Program Year One

advertisement