R Torah and Humanity in a Time of Rebirth: Rav Yehuda Amital as

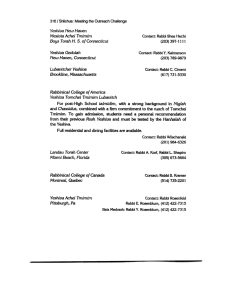

advertisement