Partnering to Meet the Child Care Training Four Profiles of Collaboration

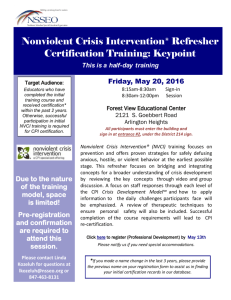

advertisement