Health and Social Service Needs of US-Citizen Children with Detained or

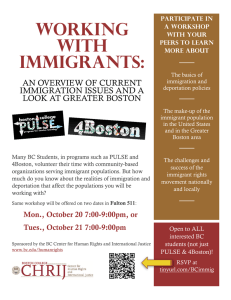

advertisement