From Cheek to Cheek Noam Sienna and Rachel Berman-Vaporis Terracotta head Stone

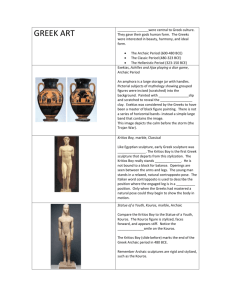

advertisement

From Cheek to Cheek Noam Sienna and Rachel Berman-Vaporis Stone figurine A nude female (now headless) holding her robe in one hand and covering herself with the other. From behind, the buttocks have maintained their finely-defined curves. About CLARC The Classical Studies Artifact Research Collection is a collection of approximately 900 objects from the Mediterranean and Near East, from the Archaic, Hellenistic, and Byzantine periods. Each year, a select number of undergraduate students are given the opportunity to work with the collection, which includes packing and unpacking the objects, photographing and researching them, and curating an exhibit in Goldfarb Library. This exhibit explores themes of beauty that are both similar to and different from our own, using the human form as represented in classical artifacts. Hellenistic A woman’s head with carefully-coiffed hair. Few details remain on the face except the soft shape of her cheeks and jaw. This selection of artifacts demonstrates a variety of forms and methods to the depiction and use of the human body during the Classical and Hellenistic periods. Egyptian styles and other art types from around the Mediterranean influenced the portrayal of the body, and the style constantly transformed and increased in complexity through the Archaic period into the Hellenistic and beyond. While the body in art was often depicted in its ideal form, the idea of human perfection is an ever-shifting phenomenon, and thus idealism had to shift with it. In the Archaic period, the beginning of Greek sculptural art, people’s bodies To Professor Ann Olga were represented in stiff and artificial poses, with idealized shapes and little Koloski-Ostrow, our detail. Around the 6th century BCE, statuary became increasingly supervisor and magistra naturalistic. The subjects were no longer impersonal larger than-life depictions, but instead were people, who were not “ordinary” if they could suprema, and to Jess afford to be immortalized in sculpture, but were at least flesh-and-blood Schaengold, our senior human beings. Greek sculpture reached a zenith of achievement in the intern and foam-cutter mid-5th century BCE, often known as the Golden Age of Athens. In this extraordinaire. period, the human form was depicted realistically but still with an eye for the ideal form; famous sculptors such as Polykleitos and Praxiteles strove for innovation in depicting movement, texture, and emotion in their art. The ideals of Greek sculpture and other art forms were spread, along with Greek culture and language, as far east as India following the conquests of Alexander the Great towards the end of 4th century BCE. The Romans later in the 2nd century BCE absorbed and emulated many aspects of Greek culture, including their classical artistic traditions, and adapted them in their own innovative way. For example, in Roman art domestic scenes were more commonly depicted in sculpture than in Greek art. Thank you Clay ‘angel’ References 1st century BCE - 1st century CE A winged male figure, perhaps Syrian. Its purpose and function are unclear. Terracotta head Glazed face A glazed ceramic face joining a handle to the body of a pot (now lost). Mirror handle (?) Gisela M. A. Richter. The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks, 1950,Yale University Press. A bronze James Whitley, The Archaeology of Ancient Greece, 2001, figure in the Cambridge University Press.Sarah Pomeroy, et al. Ancient shape of a Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. 1999, Oxford University Press. woman holding John Boardman. Greek Sculpture:The Classical Period: A Handbook. 1985, London: Thames & Hudson. her hands to her head, with a stand.