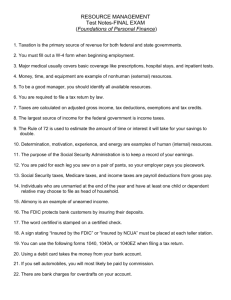

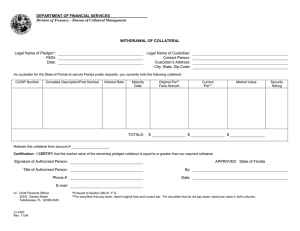

The Role of Collateral and Personal Guarantees in Relationship

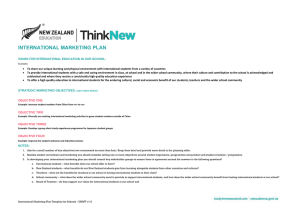

advertisement