4 6 1000 tence

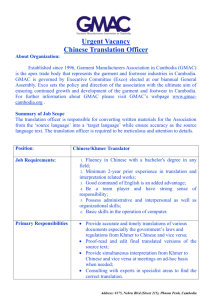

advertisement