Japan: Financial Sector Stability Assessment Update

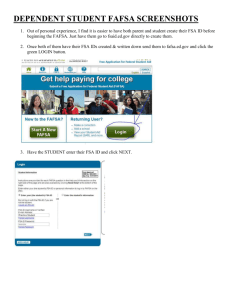

advertisement