CAPITAL INCOME TAXATION AND PROGRESSIVITY IN A GLOBAL ECONOMY Abstract

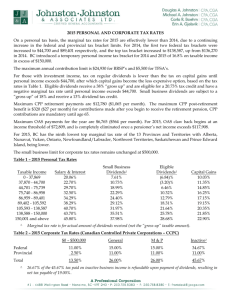

advertisement