Industrial Traces: Central Chemical & Hagerstown Shoe Company

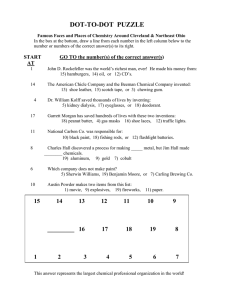

advertisement

Industrial Traces: Central Chemical & Hagerstown Shoe Company Jennifer Reut University of Virginia School of Architecture ARH 592 / LAR 526 BOOMTOWN Seminar / Fall 2002 Professors Julie Bargmann and Daniel Bluestone The Preeminent Advantages of Hagerstown 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Advantage of location. Abundant railroad communication. Abundance of growth for manufacturing sites. Good water and plenty of it. Low taxes, good public buildings. Agreeable and comfortable social conditions, elevated domestic life, good churches, cheap private and excellent public schools, abundance of good dwellings and low rents, first class hotels, profuse and cheap markets. 7. Solid banks and good stores, and public spirited tradesman, unusual and exceptionally low death rate, good drainage. 8. Cleanliness and sanitary conditions. 9. Beauty and purity of womanhood. 10. Hospitality of the people. 11. Convenience to anthracite coal beds. 12. Situated in a most magnificent agricultural region. --From the Hagerstown Daily Mail Industrial Supplement, 1904 For an entrepreneur at the turn of the century, Hagerstown, Maryland offered many advantages that might appeal to a businessman in search of opportunity. In 1911, two such business opened their doors—Central Chemical (Fig.1), a fertilizer manufacturer, and the Hagerstown Shoe Company (Fig.2). Both businesses were founded and run by local families who had some previous experience in their respective fields, and both businesses were rooted in agricultural byproducts. Despite these similarities, their profile on the landscape was very different. Hagerstown Shoe was a three-storey reinforced concrete construction with a brick exterior, located, at Franklin and Prospect, right in the center of town, a block from the tracks and two blocks away from the main square. These traces left on the landscape augment and amplify the story of Hagerstown’s industrial past, and offer some suggestions about how to integrate that history into the future. Prior to 1910, most industrial buildings were collaborations between factory owners and engineers or contractors. By the turn of the century, these collaborations resulted three basic types of industrial building materials: Timber, reinforced concrete, and structural steel. The form that these buildings took was dependent on the organization of the manufacturing, but also on site location, as public and worker opinion was minimally accommodated. Industrial buildings could be single or multiple level structures, highly specific to the processes to be conducted within, or open and flexible. Quantity of light, climate regulation, power sources required, and transportation of materials were also factors in locating a building and deciding its form. Industrial Buildings: Loft At the end of the 19th century, increasing competition and rapid industrialization combined with a series of spectacular fires in Chicago and elsewhere, resulted in two main agendas when preparing plans for a new works: Efficiency and fire safety. The first demanded that the interior space be the most efficient expression of that particular company’s assembly or production process, and the second focused on constructing factories in nonflammable materials. Other factors that owners and engineers considered included the heaviness of the machines, the amount of vibration they created, and degree of natural light necessary. In dense urban fabrics, where many labor-dependant industries were located, the loft-type building was a suitable solution to the industrialist seeking a dense building in a small lot. Loft buildings were multi-storey structures with open floors that allowed for a variety of different internal arrangements that would prove necessary for changing production process. In addition, the reinforced concrete construction could support the heavy machinery and equipment loads that industries such as textile manufacturing required. For Hagerstown Shoe Company, the structural requirements of shoe equipment, coupled with the requirement that materials be quickly moved from station to station, and the dependency on labor made the loft building the most obvious choice. The The Byron Family and the Establishment of Hagerstown Shoe Company. Like Central Chemical, Hagerstown Shoe Company was an offshoot of a locally owned business that had its roots in agricultural products. Contemporary accounts describe the tannery as producing colored leather for suitcases, bags, straps, belts, shoes, carriages and employing about 300 men.1 The Byron & Sons concern had plants in Williamsport (Fig.16) and Mercerberg, Pennsylvania and had originally been founded by Joseph Byron in New England in 1832. The company was subsequently run by his son, W.D. Byron, and then at various times his sons Henry 1 Richard H Avery, III, Wings over Hagerstown: Western Maryland Gateway to the South and its Industries. (Baltimore: Horn & Co, 1939) 47. W., William C., Edward W., Joseph C., and Lewis T. Byron were all involved in some aspect of the family businesses. By the time the Hagerstown Shoe & Legging Company was established on January 11, 1911, it appears the Byron family was already fairly affluent. The first president, Lewis T. Byron lived in an opulent house at 406 Potomac with 20 rooms on 3 floors, 7 baths and 4 fireplaces, and a library paneled with leather from his factory (Fig.17).2 After his death in 1922, his brother, Col. Joseph C. Byron who lived at 128 Prospect (Fig.18) with various members of the extended Byron family, succeeded Lewis as president until his own death in 1932. By 1919, the Byrons had opened the Byron Shoe Manufacturers 36 Antietam Street (Fig.19), which operated in tandem with the Hagerstown Shoe & Legging Company. The subsequent Byron generations became increasingly involved in state politics. William D. (1895-1941), son of Lewis, attended Exeter and Pratt, followed by a stint in the army and the family leather business. After serving as mayor of Williamsport (1926-30), he was elected Senator (1930-4) and Representative (1939-41) and served until he died in office. He was succeeded by his wife, Katharine Edgar, who served in his place from 1941-43. Their son, Goodloe E., was also a Maryland delegate (1963-66), member of the Senate (1967-70) and a Representative from 1971-78 until he also died in office. His wife, Beverly Barton Butcher Byron, took over his seat and served from 1979-93. The Byron family sold the Hagerstown Shoe Company to Cannon Shoe in 1986, when Goodloe Byron was a Senator. According to his obituary, the tannery was “forced into receivership 3 years ago [in 1976] when it had to convert from coal to oil and install a sewage treatment plant to reduce wastewater runoff into the Potomac.” 3 Hagerstown Shoe Factory: The Shoe Industry and its Workers In 1911 the Byrons rented a building on Elizabeth Street and opened the Hagerstown Legging Company, to manufacture leather leggings and a part of a harness called a Hame Tugs (Fig.20). 2 “House has a History.” Cracker Barrel (January 1977) 6. Donald P. Baker “West Maryland Representative Goodloe Byron,” Washington Post (Oct 12, 1978) Reprinted in the Congressional Record. 3 The factory building at 148 Franklin appears to have been built shortly thereafter. Shoes and canvas leggings were added to production in 1912. Due to changes in fashion and the advent of paved roads, leather and canvas leggings were dropped and shoes become the main product by 1935. By 1926, the Hagerstown Shoe Factory has added another wing to the preexisting L-shape structure (Fig.21), and by 1939, their economic prospects appear very bright: The company operates two factories, with a production of 12,000 pairs per day, employing approximately 1,000 people. Its products consist of children’s and growing girl’s shoes made in the Stitchdown, McKay and Goodyear Welt process; also men’s and boys’ Romeos, Stitchdown construction, and leather leggings.4 Fifteen years later, production was only half that number. According to Vice-president L.V. Hershey, in 1953 there were 400 employees producing 6,000 pairs a day or 1.25 million pairs a year, mainly to mail order, large chains and department stores. 5 Cannon Shoe company purchased Hagerstown Shoe in 1968 and, in October 1984 citing competition from foreign imports, the factory closed its doors for good The building was willed to the Christ’s Reformed Church by Bennett Rubin, president of Cannon Shoe.6 The church, in conjunction with the REACH organization, is endeavoring to turn the factory into a homeless shelter. Echoing the managers of shoe factories all over the east coast, Hagerstown Shoe Factory VicePresident L.V. Hershey described the business as highly completive and difficult one in which to make a profit. “Efficient operation is highly important, since a difference of as little as 2c per pair, will, in many cases mean the loss of an order…”7 This sentiment, echoed in a number of trade publications, indicates that the successful shoe manufacturer had to be at the forefront of 20 th century industrial thinking about rational organization and labor management. “It is very natural that shoe manufactures should want to know exactly where they are at, inasmuch as the field of competition is extremely keen and the margin of profit small.” 8 These conditions led some business owners to turn to labor as a potential source of cost cutting. During the early part of the 20th century, the Brown Shoe Company in St. Louis, MO was able to grab a large share of 4 Avery, 47. L.V. Hershey, September 28, 1953, 11. Source unattributed in the Washington County Historical Society Papers. 6 Julie E. Greene, “Some Concerned about Plans for Former Shoe Company.” Hagerstown Daily Mail, (November 28, 1997). 7 Hershey, 12. 8 John E. Kirwin, Shoe Factory Efficiency, (Boston: Leather & Shoe Audit System, 1910) 1. 5 the market from the historically dominant New England manufacturers by paying $10 a week to their workers for comparable work that earned $25 in Massachusetts, in part because the majority of the labor force was women or youths, or both.9 Although conditions in Hagerstown appear to be more humane, nonetheless, the Byrons and their managers must have been aware of the sensational case against Brown in 1935 that led to the establishment of the ACLU. Certainly, the business practices of such companies must have brought pressure to bear on their less ruthless competitors. Efficient shoe manufacturers focused their cost-cutting efforts in several areas: Labor, Factory Organization, Materials, and Machinery. A number of studies of the larger shoe-making industries in Lynn, Massachusetts and other cities have shown the evolution of “putting-out” system and the role of women doing home work in the development of the shoe industry in the 19 th century, and there is evidence that some factories appeared to continue this practice into the 20 th century. However, as business owners began to see profitability tied to labor oversight, the livelihood of piece workers or day laborers began to be less valuable. “There is a deep rooted belief among manufacturers that the danger flag only flies over the head of day laborer and that they alone require strict tabs to be kept,” 10 stated one observer in 1910. Not surprisingly, the presence of the supervisor became more important during this time, and the outside manager begins to be more popular at the time that Hagerstown Shoe is established. Hagerstown Shoe Company, however, continued the common industry practice of paying its workers by piecework and promoted its managers from within. By the late 1950s, 124 employees have been employed at Hagerstown Shoe for twenty-five to forty-two years, and ninety-five employees have been there for fifteen to twenty-five years. Hagerstown Shoe Company honored its long-time employees by inducting them into the Quarter Century Club, hosting a dinner and handing out certificates, door prizes, and mementos. In 1957, the Club was in its 11th year, with 151 members.11 In addition to their obvious loyalty, employees appeared to have taken great pride in their knowledge and affiliation with the shoe industry, and on at least one occasion lectured to local civic groups. 12 Larry Ward, whose father was a die cutting vendor in the pattern making department, described the management as “one of the Rosemary Feurer, “Shoe City, Factory Town,” Gateway Heritage (Fall 1988) 2-4. Kirwin, 5. 11 “Hagerstown Shoe Co. Honors New Members of 25 Year Club,” Hagerstown Daily Mail?, (cWinter 1957). 12 “History of the shoe told by official of local industry to optimists.” Hagerstown Daily Mail? (June 13, 1956). 9 10 better ones,”13 of the many shoe factories he had worked in, an assessment that is corroborated by other employee family members. Another interviewee implied that conditions, specifically the noise and fumes, would not be acceptable under current labor laws, but that “back then there was no repetitive motion injuries. People worked hard, lived hard, and lived well.” 14 Like many employees, Earl Schlotterbeck, (Fig.22) Vice-president of Manufacturing, began at Hagerstown Shoe Company as an office boy in 1915, and worked his way up through the various departments until he was dismissed after the purchase by Cannon. In addition to the Quarter Century Club, Hagerstown Shoe sponsored company picnics and provided generous Christmas gifts for some managers. The employees responded by excluding the union from the shop until the Cannon acquisition.15 How Shoes Were Made: Processes and Equipment Industrial shoe manufacturing began in the late 18 th century as artisnal work, done by a single person with the assistance of his wife or child, but by the beginning of the 20th century shoemaking had subdivided into almost 200 different tasks. In the beginning, Hagerstown Shoe manufactured shoes, leggings, and other leather products but by the 1950s they were advertised as makers of three kinds of shoes: Goodyear Welt, Cement, and Stitchdown. These three terms refer to different types of the Closing process—whereby the shoe upper is attached to the sole. It appears that shoe manufacturers specialized in types of construction rather than styles, and that these methods defined the kind of product Hagerstown Shoe Company was set up to construct. According to interviews, Hagerstown Shoe made entire shoes, not just the Closing component, and it is constructive to outline the entire process as it probably occurred within the factory. The shoe manufacturing process is divided into Patternmaking, Cutting, Closing, Lasting, Bottoming, and Finishing. In general, the shoe manufacturing process was a kind of mechanized craft— machines replicated tasks that were originally done by hand to speed production and efficiency but were heavily reliant on human skill to operate. 13 Interview with Larry Ward. December 8, 2002. Interview with Earl Schlotterbeck, Jr. December 11, 2002. 15 It appears that HSF was never unionized, while Cannon workers were members of the local 149 Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. In an interview with Earl Schlotterbeck, Jr., he states that his father and other employees successfully lobbied to keep the union out of the shop until just after the Cannon transition. 14 The process begins with the Patternmaking: constructing, designing and cutting the leather into sectional parts, grading/scaling the sizes (Fig.23), and preparing it for the factory. The Patternmaker is the most skilled and creative of the shoe/boot making workers. Cutting or “Clicking” so called because in original methods, the knife used to cut leather made a distinct click at the termination of each cut. This was the cutting of the upper leathers and was often done on a machine, although some was still done by hand. Cutters must be able to identify the grain of leather and, most importantly, arrange the patterns on the hide in a systematic and efficient way. There are three ways of cutting: exhaustive which uses every scrap, selective and the combination. Preparation for Closing. This includes marking for stitching, skiving which is removing or paring the edges, and punching perforations into the materials for decoration or sewing. Workers had a set of knives that they used to hand pare the leather as well as machines that stamped or moved the upper while the operator cut. Upper Closing. Sewing or Closing was originally specifically female labor. There were five kinds of seams: Lap, Plain, Silked, Welt, and Overseam. Sewing machines were used here as well, especially the modern “rapid” style. Goodyear Welt, Cement, and Stitchdown were part of the Closing process, and got their names from the kinds of machine used or, in the case of Cement, the sealant. Bottom Stock Cutting and Preparation. This was where the soles were prepared for attachment to the shoe. Lastings. A last is the form over and around which shoes were molded and stretched to give them their shape. Shoes appeared to be molded on the last several times in the process of being made (Fig.24). Because of the physical requirements of stretching, it was originally considered work for teams men and boys. Bottoming. This was the process of attaching the sole. Creaking is also dealt with at this point. Heels were attached through screwing and then leveled. Finishing. As the name implies, this is the final step. The finisher must be able to turn out neat and artistic work, and although this was once done by a single person, it was subsequently subdivided into several positions: Trimmers, Scourers, Setters, and Burnishers (Fig.25). The finishing process alone had twenty-two steps. Hagerstown Shoe Company produced three kinds of shoes: Stitchdowns, Welts, and Cement. A Stitchdown was a simple form in which the upper is turned outward on the sole and stitched straight through. “Stitchdown” is so called for the reason that the shoe upper is not stretched around the last and tacked to the insole or outsole, but is turned out at the sole line and stitched down to the outsole. In a “Stitchdown” the welt does not go under the last but is just a straightedged strip of leather sewed along the side (Fig.26)16 McKay is a kind of sewing machine used for Stitchdown processes. Welts were a narrow strip of leather stitched to both the upper of the shoe and the insole at one operation, called inseaming. The term Welt applies to a shoe made in this way, not just the process of attachment. The machines used are called “Goodyear” the term Goodyear Welt (Fig.27) is the term applied to shoes constructed thus. 17 The Goodyear Rapid Stitcher (Fig.28) utilized waxed the thread that was warmed with heat from the machine itself and sat upright on the floor. The Cement Process (Fig.29) refers to attachment by glue. Rubber cement was clean, strong and flexible, but gave off toxic fumes and was flammable. This is an attachment that might be used for casual or athletic shoes, where flexibility was a requirement. The process of manufacturing at Hagerstown Shoe probably followed traditional methods of construction, although individual plants may have varied. First the materials were brought in from the Byron tannery and sorted before moving off to the Cutting department. Dies were made from patterns and used to cut the leather with large stamping machines. The materials then 16 Shoe Lexicon (New York: , Boot and Shoe Recorder Company ,1934) 68. 17 Shoe Lexicon, 77. moved to the Fitting room where they were assembled and sewn. After the uppers were sewn, they went to the Closing department where the bottom insole/outsole was assembled and then attached using one of the three methods, and then lasted. Heels were then nailed on (Fig.30) and the shoe was sent to the finishing department. Completed shoes were then boxed and shipped out. Materials circulated in the factory along with a Ticket (Fig.31) that was perforated so that each station would then remove a section indicating the work was complete. It is possible that the perforated sections were also used to tally individual’s pay, as they were paid by the piece. How Shoes Were Made: Evolution of the Factory Site The interior of most shoe factories in loft type buildings featured a series of transverse benches with five to seven machines on them that could be either individually powered or powered by a single engine. Materials circulated in carts through the central aisle and light sources were from both the window and overhead and individual lamps. At Hagerstown Shoe, the interiors featured mushroom columns and wood flooring (Fig.32). There were freight elevators with cage in the back of the building, and a large overhead belt that ran the length of the floor. Individual machines would be powered via attachment to the main belt overhead. 18 Changes and approaches material flows and rational organization can be seen by analyzing the Sanborn maps (See Diagram1, App. B) over the course of about thirty years. In the 1918 Sanborn Map (Fig.33) Hagerstown Shoe was in the original L-form. The materials moved through the building vertically and horizontally with only some capitulation to rational organization. In 1924, a new wing was added to the right, and smaller dependency was in use one half block away on Kennedy (Fig.34). It is difficult to determine from the maps how the material flow had changed, due to the quality of the image. In 1950 (Fig.35), an office block has been added to the complex and the new wing is given over entirely to Stitching and Stock. It is likely that the organization of the plant did not change significantly from 1924 addition to the 1950 office and that materials moved from the central locus of the freight elevator at the back of the new wing. Hagerstown Shoe Company: Cycle and Re-cycle The environmental and cultural implications of expunging the traces of these industries demand that they be considered for preservation. A 1915 Cannon Shoe Factory building in Baltimore was 18 Interview with Earl Schlotterbeck. successfully re-adapted by the Maryland Institute College of Art as a studio exhibition space for artists and students (Fig.35) This possibility could yield a lively collaboration with the homeless shelter that is currently planned.