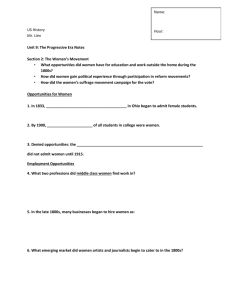

Why Celebrate Woman's History Month by Alan Singer

advertisement