The Unmet Needs of the Menominee Nation: Challenges and Opportunities Prepared for the

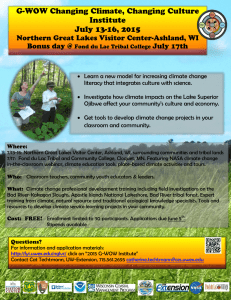

advertisement