FIFTH-YEAR REPORT MILWAUKEE PARENTAL CHOICE PROGRAM

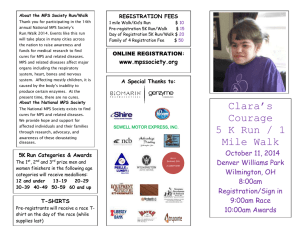

advertisement