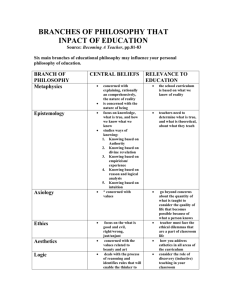

WAYS OF KNOWING AND CULTURAL AWARENESS A Thesis by

advertisement