Resident stem cells are not required for

advertisement

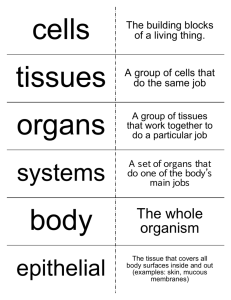

Resident stem cells are not required for exercise-induced fiber-type switching and angiogenesis but are necessary for activity-dependent muscle growth Ping Li, Takayuki Akimoto, Mei Zhang, R. Sanders Williams and Zhen Yan Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290:1461-1468, 2006. First published Jan 11, 2006; doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00532.2005 You might find this additional information useful... This article cites 32 articles, 22 of which you can access free at: http://ajpcell.physiology.org/cgi/content/full/290/6/C1461#BIBL Updated information and services including high-resolution figures, can be found at: http://ajpcell.physiology.org/cgi/content/full/290/6/C1461 Additional material and information about AJP - Cell Physiology can be found at: http://www.the-aps.org/publications/ajpcell This information is current as of May 19, 2009 . AJP - Cell Physiology is dedicated to innovative approaches to the study of cell and molecular physiology. It is published 12 times a year (monthly) by the American Physiological Society, 9650 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD 20814-3991. Copyright © 2005 by the American Physiological Society. ISSN: 0363-6143, ESSN: 1522-1563. Visit our website at http://www.the-aps.org/. Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 This article has been cited by 1 other HighWire hosted article: Point:Counterpoint: Satellite cell addition is/is not obligatory for skeletal muscle hypertrophy R. S. O'Connor and G. K. Pavlath J Appl Physiol, September 1, 2007; 103 (3): 1099-1100. [Full Text] [PDF] Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C1461–C1468, 2006. First published January 11, 2006; doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00532.2005. Resident stem cells are not required for exercise-induced fiber-type switching and angiogenesis but are necessary for activity-dependent muscle growth Ping Li, Takayuki Akimoto, Mei Zhang, R. Sanders Williams, and Zhen Yan Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina Submitted 21 October 2005; accepted in final form 6 January 2006 endurance exercise; adaptation are terminally differentiated and no longer have the ability to proliferate, but they contain a pool of myogenic stem cells, also called satellite cells, that reside between the basal lamina and sarcolemma of myofibers (19). Upon stimulation, such as injury and increased work overload, satellite cells are activated and undergo proliferation and differentiation to participate in muscle regeneration and hypertrophy (1, 28, 34). It is well known that endurance exercise, defined as repetitive, prolonged exercise of submaximal intensity, induces phenotypic changes in skeletal muscles that lead to enhanced exercise capacity and improved metabolic homeostasis (6, 32). Recent advances in molecular biology have significantly improved the understanding of exercise-induced skeletal muscle adaptation, as reported in previous studies of the skeletal muscle signaling-transcription network (2, 7, 17, 22, 30, 33). However, little is known about cellular processes such as satellite cell proliferation and differentiation in skeletal muscle adaptation induced by endurance exercise. ADULT SKELETAL MUSCLE FIBERS Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: Z. Yan, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Independence Park Facility, 4321 Medical Park Dr., Suite 200, Durham, NC 27704 (e-mail: zhen.yan @duke.edu). http://www.ajpcell.org Considering that satellite cell and other types of stem cells reside in adult skeletal muscle and could migrate from other peripheral tissues (5, 16, 19, 23), one might expect that these stem cells participate in skeletal muscle adaptation in response to exercise training if they undergo proliferation and differentiation. Indeed, increased satellite cell (muscle precursor) proliferation has been reported in various animal models of endurance exercise, including treadmill running, voluntary running, and chronic motor nerve stimulation (12, 14, 20, 25), as well as under conditions in which satellite cell proliferation induced by muscle injury and fiber-type transformation evoked by motor nerve stimulation was enhanced (18, 29). Accordingly, it has been hypothesized that myogenic stem cell proliferation is directly involved in or prerequisite to contractile activity-induced fiber-type switching. We recently obtained evidence that voluntary running stimulates cell cycle gene expression and promotes cell proliferation in mouse skeletal muscle (8) before the onset of fiber-type switching and angiogenesis (2, 3, 31). These findings prompted us to ascertain the functional role of cell proliferation in skeletal muscle adaptation in this physiological exercise model. In this study, we hypothesized that resident stem cell proliferation induced by voluntary running plays an essential role in fast-to-slow fiber-type switching, enhanced angiogenesis, and/or increased muscle mass. We first characterized temporal features of cell proliferation in mouse skeletal muscle during voluntary running using 5-bromo-2⬘-deoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling in vivo. We then determined the functional fates of the proliferative cells using long-term BrdU labeling. Finally, we used X-ray irradiation to ablate resident stem cell activity to ascertain the functional role of resident stem cell proliferation in skeletal muscle adaptation. In contrast to our hypothesis, our results have shown that only changes in muscle mass, not fiber-type switching or angiogenesis, are dependent on resident stem cell proliferation. MATERIALS AND METHODS Animals. Male C57BL/6J mice (8 wk of age) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), housed in temperaturecontrolled (21°C) quarters, maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle, and provided with water and chow ad libitum. All procedures involving these animals conformed to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Duke University Animal Use Committee. Voluntary running model. Mice were randomly assigned to sedentary control and running groups. Mice in the running group were housed individually in cages equipped with locked running wheels for 3 days for acclimatization, and they were allowed to run by unlocking The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact. 0363-6143/06 $8.00 Copyright © 2006 the American Physiological Society C1461 Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 Li, Ping, Takayuki Akimoto, Mei Zhang, R. Sanders Williams, and Zhen Yan. Resident stem cells are not required for exercise-induced fibertype switching and angiogenesis but are necessary for activity-dependent muscle growth. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 290: C1461–C1468, 2006. First published January 11, 2006; doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00532.2005.—Skeletal muscle undergoes active remodeling in response to endurance exercise training, and the underlying mechanisms of this remodeling remain to be defined fully. We have recently obtained evidence that voluntary running induces cell cycle gene expression and cell proliferation in mouse plantaris muscles that undergo fast-to-slow fibertype switching and angiogenesis after long-term exercise. To ascertain the functional role of cell proliferation in skeletal muscle adaptation, we performed in vivo 5-bromo-2⬘-deoxyuridine (BrdU) pulse labeling (a single intraperitoneal injection), which demonstrated a phasic increase (5- to 10-fold) in BrdU-positive cells in plantaris muscle between days 3 and 14 during 4 wk of voluntary running. Daily intraperitoneal injection of BrdU for 4 wk labeled 2.0% and 15.4% of the nuclei in plantaris muscle in sedentary and trained mice, respectively, and revealed the myogenic and angiogenic fates of the majority of proliferative cells. Ablation of resident stem cell activity by X-ray irradiation did not prevent voluntary running-induced increases of type IIa myofibers and CD31-positive endothelial cells but completely blocked the increase in muscle mass. These findings suggest that resident stem cell proliferation is not required for exercise-induced type IIb-to-IIa fiber-type switching and angiogenesis but is required for activity-dependent muscle growth. The origin of the angiogenic cells in this physiological exercise model remains to be determined. C1462 CELL PROLIFERATION IN MUSCLE DURING RUNNING AJP-Cell Physiol • VOL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The following primary antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis: rabbit anti-MyoD antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and rabbit anti-␥-tubulin antibody (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA). The intensities of the bands were quantified using Scion Image software. Statistical analysis. Data are presented as means ⫾ SE. For the time course experiments, one-way ANOVA was used to compare mean values of each time point with those of the sedentary group. The Dunnett test was used to determine statistically significant differences. For comparison between the sedentary and trained mice, a two-tailed Student’s t-test was performed. Two-way ANOVA, followed by the Newman-Keuls test, was used to compare results in irradiated and contralateral nonirradiated plantaris muscles from sedentary and trained mice. P ⬍ 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant for all analyses. RESULTS Voluntary running induces phasic increase of cell proliferation in mouse skeletal muscle. To define the temporal features of voluntary running-induced cell proliferation in skeletal muscle, we performed in vivo BrdU pulse labeling in plantaris muscle. As shown by indirect immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. 1, A and B), voluntary running resulted in a significant increase in BrdU-positive cells between days 3 and 14 compared with the sedentary control mice (P ⬍ 0.01). The number of BrdU-positive cells returned to the basal level after 4 wk of training. This phasic increase in BrdU labeling occurred concurrently with induced mRNA expression of cell division control protein 6 Cdc6 (Fig. 1C), a cell cycle gene that is essential for cell proliferation and DNA replication (35). Voluntary running induces cell proliferation in skeletal muscle with different functional fates. To better understand the functional role of cell proliferation in exercise-induced skeletal muscle adaptation, we traced the functional fate of the proliferative cells by labeling the proliferating cells and allowing them to differentiate into mature functional cells. The longterm BrdU labeling was achieved by daily intraperitoneal injection of BrdU during 4 wk of voluntary running. As shown in Fig. 2A, significantly more BrdU-positive nuclei were detected in plantaris muscles of sedentary control mice after long-term BrdU labeling (8.6 ⫾ 0.8/mm2) compared with the pulse-labeling results (0.9 ⫾ 0.2/mm2) (Fig. 1B). Voluntary running (4 wk) resulted in a 7.5-fold increase in BrdU-positive nuclei (102.6 ⫾ 25.2 per mm2; P ⬍ 0.01 vs. sedentary control) in plantaris muscles (Fig. 2, A and B). The percentages of BrdU-positive nuclei in plantaris muscles were 2.0 ⫾ 0.4% and 15.4 ⫾ 1.6% in sedentary and exercise-trained mice, respectively. The number of BrdU-positive nuclei in soleus muscle was significantly higher than that in plantaris muscle (12.7 ⫾ 1.8 per mm2; P ⬍ 0.001 vs. plantaris muscle) in sedentary control mice, and voluntary running resulted in a 12.5-fold increase in BrdU-positive nuclei (159.1 ⫾ 26.5 per mm2; P ⬍ 0.001 vs. sedentary soleus muscles). The percentages of BrdUpositive nuclei in soleus muscles were 1.9 ⫾ 0.4% and 20.0 ⫾ 3.7% in sedentary and exercise-trained mice, respectively. Indirect immunofluorescence was used to ascertain the functional identities of these BrdU-positive cells. The BrdU-positive cells in exercised plantaris muscle were of multiple functional fates (Fig. 2C and Table 1). In general, 32.5 ⫾ 3.8% of the BrdU-positive nuclei were confirmed to be muscle nuclei (according to relationship to laminin staining) and 28.4 ⫾ 3.2% 290 • JUNE 2006 • www.ajpcell.org Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 the wheels at the beginning of a dark cycle for 1, 3, 7, 14, or 28 days, followed by a 24-h resting period (n ⫽ 7 for each time point) as previously described (4, 31). Sedentary mice (n ⫽ 7) without access to a running wheel were used as controls. In the long-term BrdU labeling experiment, mice were randomly divided into sedentary (Sed; n ⫽ 7) and exercise groups (Ex; n ⫽ 7), and mice in the exercise group were allowed to run voluntarily for 4 wk. After single-hindlimb X-ray irradiation, mice were allowed to recover for 3 days before voluntary running for 2 or 4 wk (n ⫽ 5 for each time point). A separate group of irradiated mice with no running wheel access were used as sedentary controls (n ⫽ 5). X-ray irradiation of a single hindlimb did not have a significant impact on running activity (data not shown). BrdU labeling in vivo. To pulse label proliferative cells in skeletal muscles, the mice were allowed to run voluntarily for 1, 3, 7, 14, or 28 days. A single dose of BrdU (500 mg/kg body wt) was injected intraperitoneally immediately after the last bout of running activity, followed by a 24-h resting period (by locking running wheels) before samples were harvested. For long-term labeling, the mice were allowed to run voluntarily for 28 days, and BrdU (500 mg/kg body wt) was injected intraperitoneally daily. Sedentary mice injected with BrdU were used as controls in both pulse-labeling and long-term labeling experiments. Ablation of resident stem cells in hindlimb muscles by X-ray irradiation. Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium, and their right hindlimbs were exposed to a single dose of 2,500-rad ionizing irradiation for 23 min using an XRAD-320 orthovoltage unit (Precision X-ray, East Haven, CT). The rest of the animal was shielded from the radioactive source using a 2-cm-thick lead attenuator. Immunohistochemistry. Muscles were harvested, saturated in 30% sucrose-PBS for ⬃2 h, placed into optimal cutting temperature (OCT) tissue-freezing medium (Miles Pharmaceuticals, West Haven, CT), and frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane. Frozen sections (6 m) were cut using a cryostat and placed onto microscope slides (Superfrost Plus; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Before being stained, the sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 10 min at 4°C, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100-PBS for 10 min at 4°C, and then blocked in 5% normal goat serum (NGS)-PBS for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with a different primary antibody in 5% NGS-PBS at 4°C overnight. Rat anti-CD-31 antibody (1:25 dilution; Serotec, Raleigh, NC) and rat anti-laminin antibody (1:100 dilution; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) were used for endothelial cells and basal lamina, respectively. Three consecutive washes with PBS for 5 min each were followed by sequential incubation with secondary antibodies (rhodamine or FITC conjugated, 1:25 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) at room temperature for 30 min. The sections were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS for 5 min, and we continued to stain them for BrdU. In brief, each slice was treated in 1 N HCl at 37°C for 1 h, followed by incubation with either unconjugated (1:25 dilution) or Alexa Fluor-conjugated mouse anti-BrdU primary antibody (1:25 dilution; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) overnight at 4°C. If unconjugated primary antibody was used, we proceeded to use secondary antibody as mentioned above. Immunofluorescence was also performed as described previously (31) for type IIa plantaris muscle fibers. Images were captured under a confocal microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) and further analyzed using Scion Image software (Scion, Frederick, MD). The percentage area comprising type IIa fibers was calculated in ⬎100 fibers for each muscle. The capillary density was calculated by counting CD31-positive cells and measuring the total area for ⬎100 fibers for each muscle. Immunoblot analysis. Samples were processed as previously described (3). Protein concentration was determined using the RC DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Total protein (60 g) was resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and immunodetected using an advanced CELL PROLIFERATION IN MUSCLE DURING RUNNING C1463 Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 Fig. 1. Voluntary running induces a phasic increase of cell proliferation in mouse plantaris muscle. A: indirect immunofluorescence staining of plantaris muscle sections from sedentary control (Sed) and 2-wk exercise-trained (Ex) mice. A section of the duodenum (Gut) was used as a positive control for cell proliferation. All sections were stained with anti-5-bromo-2⬘-deoxyuridine (anti-BrdU) antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green) and nuclear DNA with propidium iodide (PI; red). B: quantitative data for BrdU-positive nuclei in plantaris muscle (n ⫽ 7 for each time point). **P ⬍ 0.01, statistically significant difference vs. sedentary control muscle. C: semiquantitative RT-PCR for Cdc6 mRNA. Representative images (top) of RT-PCR products for Cdc6 mRNA and reference control of Gapdh mRNA are shown. Quantitative data (bottom) also are presented (n ⫽ 7 for each time point). *P ⬍ 0.05, statistically significant difference vs. sedentary control (running time ⫽ 0). AJP-Cell Physiol • VOL 290 • JUNE 2006 • www.ajpcell.org C1464 CELL PROLIFERATION IN MUSCLE DURING RUNNING Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 Fig. 2. Identification of functional fates for the proliferative cells using long-term BrdU labeling. A: indirect immunofluorescence staining of muscle sections from sedentary control and 4-wk exercise-trained plantaris muscles with daily intraperitoneal injection of BrdU. All sections were stained with anti-BrdU antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green) and nuclear DNA with PI (red). B: quantitative data for BrdU-positive nuclei in plantaris (PL) and soleus (SO) muscles (n ⫽ 7). ***P ⬍ 0.001. C: indirect immunofluorescence staining of muscle sections from 4-wk exercise-trained plantaris muscles. To identify BrdU-positive muscle nuclei (top), sections were stained with anti-BrdU antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green) as well as anti-laminin antibody followed by rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (red). Central (arrowhead) and peripheral (arrow) nuclei could be identified easily. To determine the angiogenic fate of the proliferative cells (bottom), sections were stained with anti-BrdU antibody followed by rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (red) as well as anti-CD31 antibody followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Arrows indicate BrdU-CD31 double-positive cells. D: immunoblot analysis for MyoD. Representative images of MyoD and loading control ␥-tubulin (top) and quantitative data (n ⫽ 5 for each time point) are shown. **P ⬍ 0.01, statistically significant difference vs. sedentary control (running time ⫽ 0). were angiogenic (i.e., CD31-positive) cells. The rest of the BrdU-positive nuclei were of unknown origin in the interstitial space outside the basal lamina sheath. The involvement of myogenic stem cells was also implicated by transiently induced expression of myogenic regulatory factor MyoD during longAJP-Cell Physiol • VOL term voluntary running, with peak expression occurring at 2 wk (Fig. 2D). Altogether, these findings provide direct evidence that the majority of the proliferative cells induced by voluntary running in skeletal muscle participate in myogenesis and angiogenesis. 290 • JUNE 2006 • www.ajpcell.org CELL PROLIFERATION IN MUSCLE DURING RUNNING Table 1. Indirect immunofluorescence identification of functional fates of proliferative cells in adult mouse skeletal muscles in response to voluntary running Muscle cell nuclei Central myonuclei Peripheral myonuclei Endothelial cell nuclei Plantaris, n ⫽ 7 Soleus, n ⫽ 7 13.8⫾3.8% 18.7⫾1.7% 28.4⫾3.2% 20.3⫾4.5% 14.1⫾1.1% 20.5⫾2.7% Values are means ⫾ SE; n ⫽ 7 muscles per group. The myogenic fate of the proliferative cells in 4-wk exercise-trained plantaris muscles was determined using indirect immunofluoresence staining on the basis of anatomic relationship to basal lamina (stained for laminin) (see Fig. 2C, top). The angiogenic fate of the proliferative cells was determined using indirect immunofluoresence staining of 5-bromo-2⬘-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-positive nuclei and the endothelial marker CD31. BrdU-CD31 double-positive cells are considered to have the angiogenic fate (see Fig. 2C, bottom). AJP-Cell Physiol • VOL running at 2 wk. We observed a trend of muscle mass increase (P ⫽ 0.06) in nonirradiated plantaris muscles at 4 wk of running, which was completely abolished by irradiation. Irradiated soleus muscles showed a similar response to voluntary running, except that there also was decreased muscle mass in the sedentary mice (Fig. 3G). DISCUSSION In the present study, we have defined a robust, phasic increase of cell proliferation in mouse plantaris muscle during long-term voluntary running. The increase was associated with fiber-type transformation, enhanced angiogenesis, and muscle growth. These findings confirmed and extended our previous observations in the same exercise model that voluntary running induces cell cycle gene expression and cell proliferation in the recruited skeletal muscles. Consistent with these findings, long-term in vivo BrdU labeling revealed that voluntary running-induced cell proliferation contributed to myogenesis and angiogenesis in plantaris muscles. Most important, we have demonstrated that ablation of resident stem cell activity blocks activity-induced muscle growth but has no impact on exerciseinduced fiber-type switching and angiogenesis. Endurance exercise training has been characterized by the adaptive changes in fiber-type composition and microvasculature (6, 32), and less attention has been paid to the effect on muscle mass. It was recently shown that voluntary running with resistance induces increases in recruited skeletal muscle mass in mice and rats (13, 15), supporting the notion that workload is a potent determinant of muscle mass in endurance exercise. However, it is worth noting that in these studies, animals that ran with little or no load also showed a trend or a significant increase in plantaris muscle mass after long-term voluntary running (7– 8 wk) compared with sedentary control mice. These findings raised an issue of activity-dependent muscle growth, which is also supported by the finding that treadmill running induces moderate muscle growth in rats (26). Our findings that voluntary running promotes muscle growth in plantaris and soleus muscles are in complete agreement with these previous findings. Importantly, we have extended the findings to confirm that the muscle growth induced by voluntary running in mice is dependent on resident myogenic stem cell function. X-ray irradiation not only may elicit DNA damage and cell cycle checkpoint to block satellite cell proliferation but also may result in damage to the microenvironment of the muscle, and collectively these effects may impair the ability of satellite cells to fulfill their normal function in promoting muscle growth in response to exercise. Several other features of cell proliferation in skeletal muscle have been revealed in this study. First, we have found that in sedentary mice, soleus muscle, a muscle that is frequently recruited for antigravity postural activity, had significantly more proliferating cells per unit of cross-sectional area than the adjacent plantaris muscle (Fig. 2B). Second, voluntary running resulted in an ⬃10-fold increase of BrdU-positive nuclei shown by either pulse labeling at 2 wk of running or long-term labeling during 4 wk of voluntary running, and it induced an ⬃10% increase in muscle mass in the recruited plantaris and soleus muscles (Fig. 3G). Third, irradiation-mediated ablation of resident stem cells resulted in decreased muscle mass in frequently recruited soleus muscle, but not in plantaris muscle, 290 • JUNE 2006 • www.ajpcell.org Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 Resident stem cell activity is not required for voluntary running-induced fiber-type switching and angiogenesis. To determine the functional role of resident stem cell proliferation in skeletal muscle adaptation, we used X-ray irradiation to ablate resident stem cells in a single hindlimb before the start of long-term voluntary running. We chose a dose of 2,500 rad on the basis of our previous finding that this dose of local irradiation is sufficient to block myogenic stem cell-mediated skeletal muscle regeneration in vivo (34). One-hindlimb X-ray irradiation did not significantly affect daily running distance compared with the nonirradiated mice that exercised for the same running distance in the above-described time course experiment (8.7 ⫾ 0.4 km/day for irradiated mice vs. 9.9 ⫾ 0.7 km/day for nonirradiated mice, n ⫽ 5–7; P ⬎ 0.05). X-ray irradiation did not alter the number of BrdU-positive cells in sedentary control mice but did reduce significantly the increase in BrdU labeling in the trained mice (14.6 ⫾ 2.0 BrdU-positive cells/mm2 in nonirradiated mice vs. 4.9 ⫾ 0.7 BrdU-positive cells/mm2 in mice with irradiated plantaris muscle; P ⬍ 0.001) at 2 wk of running (Fig. 3A). To assess the functional consequence of stem cell ablation, we performed indirect immunofluorescence to characterize skeletal muscle adaptation in irradiated muscles after exercise training and compared the results with the nonirradiated contralateral muscles. Irradiation had no significant impact on type IIb-to-IIa fiber transformation (Fig. 3, B and C), which was also confirmed using Western blot analysis for myosin heavy chain (MHC) type IIa protein (Fig. 3D). Irradiation did not affect the increase of CD31-positive endothelial cells in plantaris muscle after 4 wk of voluntary running (Fig. 3, E and F). Resident stem cell activity is required for voluntary runninginduced muscle growth. It has been reported that voluntary running with increased workload results in significant skeletal muscle hypertrophy in soleus and plantaris muscles (13, 15). In those studies, voluntary running with no or low resistance induced moderate increases in muscle mass. To determine the effect of long-term voluntary running on muscle mass in skeletal muscle in the present study, we measured the muscle mass for the soleus and plantaris muscles in both irradiated and nonirradiated hindlimbs at 2 and 4 wk of voluntary running (normalized to body wt) and compared those data with those from the sedentary mice. Irradiation did not affect the muscle mass in plantaris muscles from sedentary mice but completely blocked the increase in muscle mass induced by voluntary C1465 C1466 CELL PROLIFERATION IN MUSCLE DURING RUNNING even in sedentary mice (Fig. 3G). This treatment blocked voluntary running-induced increases in muscle mass in both soleus and plantaris muscles. Collectively, these findings strongly support the notion that contractile activity promotes muscle growth through myogenic cell proliferation. We have also confirmed that voluntary running is associated with muscle injury and regeneration, as evidenced by the detection of central nuclei (Fig. 2C) and induction of MyoD protein expression (Fig. 2D). MyoD plays an essential role in muscle regeneration (21). The finding that voluntary running-induced cell proliferation in plantaris muscle reversed beyond day 14 despite continued exercise suggests that cell proliferation is associated with a process as a response to running activity in untrained muscle, but not in trained muscle, and/or associated with the adaptation process. It is likely that both muscle injury and muscle adaptation contribute to the increased cell proliferation in this AJP-Cell Physiol • VOL voluntary running model. If it were due only to muscle injury, it would suggest that chronic exercise results in remodeling of the muscle-rendering resistance to the same injury stimulus. Regardless of whether satellite cell proliferation is required for fast-to-slow fiber-type switching has been an intriguing question in the field of exercise physiology. Previous findings in animal models of compensatory hypertrophy (surgical removal of synergistic muscles) show that adaptations in MHC gene expression are not significantly affected by satellite cell sterilization (1, 27, 28), which argues against the hypothesis that satellite cell proliferation plays an essential role in contractile activity-induced fiber-type transformation. However, before our present study, it remained questionable whether the results were applicable to endurance exercise. Our findings have extended these previous findings and provide clear evidence, in a physiological model of endurance exercise, that 290 • JUNE 2006 • www.ajpcell.org Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 Fig. 3. Resident stem cell proliferation is required for voluntary running-induced muscle growth, but not for fiber-type switching and angiogenesis. A: quantitative data for indirect immunofluorescence for pulse-labeled BrdU-positive nuclei in nonirradiated (NI) or irradiated (IR) plantaris muscles in sedentary control or 2-wk exercise trained mice (n ⫽ 5). ***P ⬍ 0.001. B: indirect immunofluorescence staining of type IIa myofibers. An increased percentage of type IIa myofibers was present in trained plantaris muscles, regardless of X-ray irradiation. C: quantitative data for type IIa myofiber surface area in plantaris muscles (n ⫽ 5). *P ⬍ 0.05. ***P ⬍ 0.001. D: immunoblot analysis for MHC type IIa protein. Representative images of MHC type IIa and loading control ␥-tubulin are shown. CELL PROLIFERATION IN MUSCLE DURING RUNNING C1467 Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 Fig. 3—Continued. E: indirect immunofluorescence staining of CD31-positive capillary endothelial cells in plantaris muscles that were not irradiated (NI) and in those that were X-ray-irradiated (IR) from sedentary control or 4-wk exercise trained mice. An increase in CD31-positive capillary endothelial cells in trained plantaris muscles occurred regardless of X-ray irradiation. F: quantitative data for capillary density in plantaris muscles (n ⫽ 5). ***P ⬍ 0.001. G: comparison of muscle mass (normalized to body wt) in soleus and plantaris muscles that either were or were not irradiated from sedentary control or exercise-trained mice. *P ⬍ 0.05. **P ⬍ 0.01. ***P ⬍ 0.001. fiber-type switching does not require active proliferation of resident myogenic stem cells. An unexpected finding in this study is that irradiated muscles showed significant amount of residual activity of cell proliferation during voluntary running. There are several possibilities that could explain the residual cell proliferation in the irradiated skeletal muscles. First, it is possible that the radiation dose used was insufficient to ablate all of the resident stem cells, although we previously used this radiation dose in the same strain of mice to block cardiotoxin-induced skeletal muscle regeneration (34). The fact that irradiation resulted in a complete block of voluntary running-induced muscle growth provides evidence that the X-ray radiation dosage was sufficient to block myogenic cell function. Second, some of the resident stem cells may have survived irradiation to promote delayed AJP-Cell Physiol • VOL cell proliferation. Recent reports have indicated that there are stem cell populations within skeletal muscle that appear to be resistant to radiation-induced damage (11). Third, stem cells from extramuscular tissues may migrate via the circulation to the skeletal muscle to compensate for the loss of resident stem cells. This latter scenario is particularly intriguing and could be of important functional significance. Although increasing evidence supports the hypothesis that resident satellite cells are self-sufficient as a source of muscle regeneration (9), we cannot exclude the possibility that irradiated muscle could undergo hypertrophy with the participation of stems cells other than resident myogenic stem cells if the mice were allowed to run for a longer period. Irradiation had no significant impact in this study on angiogenesis induced by exercise. This finding raised several inter- 290 • JUNE 2006 • www.ajpcell.org C1468 CELL PROLIFERATION IN MUSCLE DURING RUNNING ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank Curtis Gumbs for technical support and Jin Yan for careful proofreading of the manuscript. Present address of T. Akimoto: Institute for Biomedical Engineering, Consolidated Research Institute for Advanced Science and Medical Care, Waseda University, Waseda-Tsurumaki 513, Shinjuku, Tokyo 162-0041, Japan. GRANTS This work was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant R01 AR-050429-01 and American Heart Association Grant 0130261N (to Z. Yan). REFERENCES 1. Adams GR, Caiozzo VJ, Haddad F, and Baldwin KM. Cellular and molecular responses to increased skeletal muscle loading after irradiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C1182–C1195, 2002. 2. Akimoto T, Pohnert SC, Li P, Zhang M, Gumbs C, Rosenberg PB, Williams RS, and Yan Z. Exercise stimulates Pgc-1␣ transcription in skeletal muscle through activation of the p38 MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem 280: 19587–19593, 2005. 3. Akimoto T, Ribar TJ, Williams RS, and Yan Z. Skeletal muscle adaptation in response to voluntary running in Ca2⫹/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1311–C1319, 2004. 4. Allen DL, Harrison BC, Maass A, Bell ML, Byrnes WC, and Leinwand LA. Cardiac and skeletal muscle adaptations to voluntary wheel running in the mouse. J Appl Physiol 90: 1900 –1908, 2001. 5. Asakura A, Seale P, Girgis-Gabardo A, and Rudnicki MA. Myogenic specification of side population cells in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 159: 123–134, 2002. 6. Booth FW and Baldwin KM. Muscle plasticity: energy demand and supply processes. In: Handbook of Physiology: Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems, edited by Rowell LB and Shepard JT. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1996, sect. 12, chapt. 24, p. 1075–1123. 7. Chin ER, Olson EN, Richardson JA, Yang Q, Humphries C, Shelton JM, Wu H, Zhu W, Bassel-Duby R, and Williams RS. A calcineurindependent transcriptional pathway controls skeletal muscle fiber type. Genes Dev 12: 2499 –2509, 1998. 8. Choi S, Liu X, Li P, Akimoto T, Lee SY, Zhang M, and Yan Z. Transcriptional profiling in mouse skeletal muscle following a single bout of voluntary running: evidence of increased cell proliferation. J Appl Physiol 99: 2406 –2415, 2005. 9. Collins CA, Olsen I, Zammit PS, Heslop L, Petrie A, Partridge TA, and Morgan JE. Stem cell function, self-renewal, and behavioral heterogeneity of cells from the adult muscle satellite cell niche. Cell 122: 289 –301, 2005. AJP-Cell Physiol • VOL 10. Fareh J, Martel R, Kermani P, and Leclerc G. Cellular effects of beta-particle delivery on vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells: a dose-response study. Circulation 99: 1477–1484, 1999. 11. Heslop L, Morgan JE, and Partridge TA. Evidence for a myogenic stem cell that is exhausted in dystrophic muscle. J Cell Sci 113: 2299 –2308, 2000. 12. Irintchev A and Wernig A. Muscle damage and repair in voluntarily running mice: strain and muscle differences. Cell Tissue Res 249: 509 – 521, 1987. 13. Ishihara A, Roy RR, Ohira Y, Ibata Y, and Edgerton VR. Hypertrophy of rat plantaris muscle fibers after voluntary running with increasing loads. J Appl Physiol 84: 2183–2189, 1998. 14. Jacobs SC, Wokke JH, Bar PR, and Bootsma AL. Satellite cell activation after muscle damage in young and adult rats. Anat Rec 242: 329 –336, 1995. 15. Konhilas JP, Widegren U, Allen DL, Paul AC, Cleary A, and Leinwand LA. Loaded wheel running and muscle adaptation in the mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H455–H465, 2005. 16. LaBarge MA and Blau HM. Biological progression from adult bone marrow to mononucleate muscle stem cell to multinucleate muscle fiber in response to injury. Cell 111: 589 – 601, 2002. 17. Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN, Lowell BB, Bassel-Duby R, and Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 418: 797– 801, 2002. 18. Maier A, Gambke B, and Pette D. Degeneration-regeneration as a mechanism contributing to the fast to slow conversion of chronically stimulated fast-twitch rabbit muscle. Cell Tissue Res 244: 635– 643, 1986. 19. Mauro A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 9: 493– 495, 1961. 20. McCormick KM and Thomas DP. Exercise-induced satellite cell activation in senescent soleus muscle. J Appl Physiol 72: 888 – 893, 1992. 21. Megeney LA, Kablar B, Garrett K, Anderson JE, and Rudnicki MA. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev 10: 1173–1183, 1996. 22. Naya FJ, Mercer B, Shelton J, Richardson JA, Williams RS, and Olson EN. Stimulation of slow skeletal muscle fiber gene expression by calcineurin in vivo. J Biol Chem 275: 4545– 4548, 2000. 23. Polesskaya A, Seale P, and Rudnicki MA. Wnt signaling induces the myogenic specification of resident CD45⫹ adult stem cells during muscle regeneration. Cell 113: 841– 852, 2003. 24. Prior BM, Yang HT, and Terjung RL. What makes vessels grow with exercise training? J Appl Physiol 97: 1119 –1128, 2004. 25. Putman CT, Dusterhoft S, and Pette D. Satellite cell proliferation in low frequency-stimulated fast muscle of hypothyroid rat. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C682–C690, 2000. 26. Riedy M, Moore RL, and Gollnick PD. Adaptive response of hypertrophied skeletal muscle to endurance training. J Appl Physiol 59: 127–131, 1985. 27. Rosenblatt JD and Parry DJ. Adaptation of rat extensor digitorum longus muscle to ␥ irradiation and overload. Pflügers Arch 423: 255–264, 1993. 28. Rosenblatt JD and Parry DJ. Gamma irradiation prevents compensatory hypertrophy of overloaded mouse extensor digitorum longus muscle. J Appl Physiol 73: 2538 –2543, 1992. 29. Takahashi M, Miyamura H, Eguchi S, and Homma S. The effect of bupivacaine hydrochloride on skeletal muscle fiber type transformation by low frequency electrical stimulation. Neurosci Lett 155: 191–194, 1993. 30. Wang YX, Zhang CL, Yu RT, Cho HK, Nelson MC, Bayuga-Ocampo CR, Ham J, Kang H, and Evans RM. Regulation of muscle fiber type and running endurance by PPAR␦. PLoS Biol 2: e294, 2004. 31. Waters RE, Rotevatn S, Li P, Annex BH, and Yan Z. Voluntary running induces fiber type-specific angiogenesis in mouse skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1342–C1348, 2004. 32. Williams RS and Neufer PD. Regulation of gene expression in skeletal muscle by contractile activity. In: The Handbook of Physiology: Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems, edited by Rowell LB and Shepard JT. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc., 1996, sect. 12, chapt. 25, p. 1124–1150. 33. Wu H, Kanatous SB, Thurmond FA, Gallardo T, Isotani E, BasselDuby R, and Williams RS. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle by CaMK. Science 296: 349 –352, 2002. 34. Yan Z, Choi S, Liu X, Zhang M, Schageman JJ, Lee SY, Hart R, Lin L, Thurmond FA, and Williams RS. Highly coordinated gene regulation in mouse skeletal muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem 278: 8826 – 8836, 2003. 35. Yan Z, DeGregori J, Shohet R, Leone G, Stillman B, Nevins JR, and Williams RS. Cdc6 is regulated by E2F and is essential for DNA replication in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 3603–3608, 1998. 290 • JUNE 2006 • www.ajpcell.org Downloaded from ajpcell.physiology.org on May 19, 2009 esting questions regarding the cellular processes for activityinduced angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Angiogenesis in skeletal muscle can occur by intussusception or sprouting (for review, see Ref. 24), which requires increases in endothelial cells, presumably through cell proliferation. Our findings suggest that either 1) endothelial cells are resistant to X-ray irradiation, or 2) other progenitor cells from extramuscular sources participate in exercise-induced angiogenesis. It should be pointed out that irradiation at the dose used in this study had previously been shown to block the proliferation of endothelial cells in vitro (10). It is unlikely that endothelial cells in skeletal muscle are uniquely resistant to irradiation. Thus endothelial progenitor cells may be recruited from the circulation. The possibility that circulating endothelial progenitor cells plays an essential role in endurance exerciseinduced angiogenesis is worthy of future investigation. In summary, in the present study, we have defined for the first time some temporal and functional features of cell proliferation in skeletal muscle in a physiological model of endurance exercise. The results indicate that cell proliferation induced by voluntary running is required for activity-dependent muscle growth but not for fiber-type switching and angiogenesis.