Document 14106077

advertisement

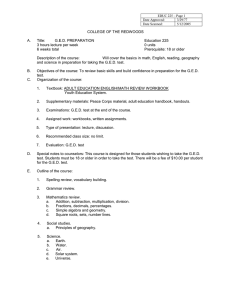

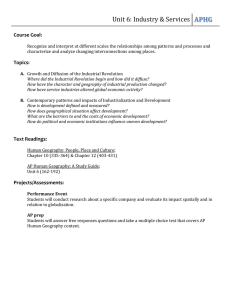

Educational Research (ISSN: 2141-5161) Vol. 1(7) pp. 219-225 August 2010 Available online http://www.interesjournals.org/ER Copyright ©2010 International Research Journals Full Length Research Paper Application of computer based resources in Geography education in secondary schools Joseph Osodo1, Francis Chisikwa Indoshi1, Omolo Ongati2 1 Department of Educational Communication, Technology and Curriculum Studies, Maseno University, Private Bag, Maseno, Kenya. 2 Department of Mathematics, Maseno University, Private Bag, Maseno, Kenya. Accepted 09 August, 2010 Several schools in the developing countries face escalating demands on access to finite computer based resources in teaching and learning. Perennial lack of access to relevant educational computer hardware and software often impede geographic instruction in many institutions. In Kenya, there is increased advocacy and adoption of computer resources in Geography education. Yet the context for this implementation has not been examined as to its potency thereby leaving the innovation to chance. The purpose of the study was to establish the availability, extent and potential utilization of computer based resources in Geography education in secondary schools. The design of the study was descriptive surveys that were conducted in Kisumu District of Nyanza Province, Kenya. The study targeted 240 secondary school teachers and 3500 form three high school students. Simple random sampling technique was used to select a sample of 80 teachers and 1165 form three Geography students. Questionnaire surveys were used to collect data. To ascertain reliability, the test-retest reliability procedure was performed. Analysis of data was done by use of descriptive statistics. The study found that no school in Kisumu District had computers dedicated for teaching and learning Geography and computer use for unrelated duties was minimal, uncoordinated and lacking in innovation. The study recommended that it is of necessity to motivate, facilitate and equip secondary school Geography students and teachers with requisite knowledge and expertise on innovative computer uses. Keywords: Computer based-resources, geographic instruction, availability, utilization. INTRODUCTION The ability of existing educational approaches to impart knowledge, skills and values appropriate to a rapidly changing world has been questioned by educationists, researchers as well as employers. Such concerns are stimulating a growth in the application of educational technology and hence need to be addressed. Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills play a key role in promoting economic development of a country. Many of the productivity gains in the developed world economies over the past two decades are attributable to the impact of I.C.Ts, especially computers. Information and Communication Technology have a direct role to play in education and if appropriately used, can bring many *Corresponding author E-mail: findoshi@yahoo.com benefits to the education sector (Government of Kenya, 2005). For instance, it provides new opportunities for teaching and learning including offering opportunity for more student centered teaching, opportunity to reach more learners, greater opportunity for teacher-to-teacher and student-to-student communication and collaboration, greater opportunities for multiple technologies delivered by teachers, creating motivation in learning amongst students and offering access to a wider range of courses. The computer has been identified as the most efficient ‘stand-alone’ technology that is able to make teaching and learning situations more meaningful and fruitful than it has ever been before (Wabuyele, 2006; Osodo, 1999; Amory, 1997). Many schools face escalating demands on access to finite computer resources, including computer suites, and, lack of access at required times often discourage 220 Educ. Res. Geography departments from using computers. There are also relatively few opportunities for continuing professional development in the use of computers in Geography education. In many schools, weaknesses in Geography education are associated with limitations in the use of computer technology and strategic management of cross-curricular ICTs (U.K., 2004). Good teaching ought to be based on clear expectations of geographical outcomes, with good preparation and planning which provide a number of linked activities to maintain pace and pupils’ interest. This was demonstrated in the United Kingdom (U.K.) where high school Geography students used ‘Kenya: the final frontier’ CD-ROM to research aspects of the Maasai’s way of life. The materials were used as a source of images alongside text at an appropriate level. This had a positive effect on learners’ comprehension of the concepts taught (U.K., 2004). In Kenya and other developing countries, there is currently limited inclusion of real-world learning experiences in the traditional classroom setting (Kinuthia, 2009; Duffy and Cunningham, 1996). Mostly, the content presented in the classroom is disconnected from its realworld context. This contextual dichotomy tended to have a negative impact on the learning process, adversely affecting learner motivation in particular (Henning, 1998). At the same time, real-world learning situated in realworld contexts has been shown to have positive impacts on learning and learner motivation (Papastergiou, 2009; Rieber, 2005; Duffy and Cunningham, 1996). Educational simulations have been found to provide a solution to this by providing some aspects of real-world learning in the traditional classroom. Therefore, this study sought to address the mismatch identified herein that even though computer simulations have been proved to have a positive impact on learners’ performance, not many educators use them in teaching and learning innovatively. Likewise, in the few cases where they are used, they are mainly in the developed economies, emphasis being in science oriented subjects. Also, none of the approaches incorporate simulations with traditional teaching and learning methodologies. Over the last few years, there has been a rapid growth in the range and sophistication of new I.C.T.s (such as radio, video, television and so on) in teaching and learning Geography within the developing countries. In particular, computer technology has been used to improve the quality of Geography education in schools because of its robust nature in displaying graphics and simulations (Castleford, 1998). Positive outcomes of using technology in education have led many governments to initiate programs for the integration of technology into schools. In the US, around $8 billion was spent by school districts in the 2003-2004 school year alone to equip schools with necessary technology, primarily in the form of computers. Similarly, in the US, the computer-to-student ratio was 1:3.8 and the internet- connected computer-to-student ratio was 1:4.1 in 2004. The computer-to-student ratio in schools was around 1:7 in Canada and the UK in 1999 and the same ratio in those countries is close to that of the US (Demirci, 2009). The situation in Kenyan schools is yet to be established. There are already a wide range of computer uses in educational endeavours especially in the developed economies such as the UK and the USA, and more uses are being explored. The internet can be used by staff to support efficient course administration and to assist students to manage their learning. It can assist in achieving many features of flexible delivery, including student choice in the time, place and pace of study. The internet, particularly, can be used to support a variety of teaching and learning tasks, including distributing information that could be conveyed in other ways; e.g., a course syllabus is available electronically instead of on paper, or photos appear on a website instead of being shown around in class; giving access to information storehouses; e.g., the internet can be used as an online library giving access to information sources and databases; providing alternative means of communication (e.g., e-mail, electronic bulletin boards, chat rooms, desktop videoconferencing) for both administrative and instructional purposes. Other uses of the internet include delivering formative and summative assessment tasks. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the commercial product QuestionMark has wide usage, being the chosen package in about two-thirds of all the Higher Education Institutions that use Computer Aided Assessment. Developed primarily as a Windows-based version, their relatively new product is Web based; supporting online course and staff evaluation exercises; delivering materials in multiple media that would be difficult to transmit by other means, e.g., a text explanation can be supplemented with pictures, sounds, video clips, links to other sites, simulations. CD-ROMs are used for storing and distributing large data sets of numerical, graphical or cartographic information. It can also be used for giving students active, hands-on, interactive experience in analyzing information or solving problems. For instance, a student can acquire data, processes it, make a map, and develop a presentation. An example of such software available on CD-ROM, is Exploring the Nardoo (University of Wollongong, 1996), a virtual inland river environment where research questions can be explored and environmental management strategies simulated; allowing students to work collaboratively (e.g., students at different institutions working on a common problem). An example is the 'Middle East Politics Simulation' developed at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, where students participate in role-playing exercises conducted using the Internet or by videoconferencing. Groups of Political Science students in Australia, New Zealand and the United States play the role of prominent leaders in the Middle East, USA or Europe, attempting to resolve a specific political, social, economic or Osodo et al. 221 environmental issue, after carrying out research to identify the background, interests and agenda of their particular character. In other cases, the simulation has been modified to involve scenario building between groups of Political and Environmental Science students, for example in exploring conflicts over water allocation in the Middle East (Alexander et al., 1998; Alexander and Blight, 1996). Even though the internet has been used for such tasks, the challenge is to make more innovative uses of the technology in order for the real potential of the technology to be realized. These uses are more prevalent in the developed countries as opposed to the developing ones. The situation as regards computer use in Geography in Kenya is yet to be established. Potential benefits of computer technology in Geography education can be identified as follows: resource savings are possible in some circumstances: automating repetitive, labour-intensive activities such as skills training can save staff time; use of e-mail for staff-student contact can save time and allow broadcasts of urgent messages or new information; virtual field trips can offer improved preparation before real field visits, or can provide a partial substitute for them; access to an enhanced range of information resources: compared with a conventional library, an online virtual library offers timeliness (constant updating of information), multiplicity (many users can access a resource simultaneously) and variety or balance (multiple web sites can be used to represent contrasting views e.g. on an environmental issue). Use of ICT can facilitate enhanced student learning, by supporting and encouraging the adoption of contemporary effective practices, e.g. a constructivist model of education (Duffy and Cunningham, 1996), resource-based learning, flexible learning (Wade et al., 1994), asynchronous virtual or online tutorials can produce educational benefits quite different from conventional tutorials for different groups. There is evidence that they benefit less assertive or more reflective students, facilitate deeper interaction and generate active participation by student groups marginalized by other methods (Harasim et al., 1995). Also, electronic communications can support enhanced collaborative learning (Johnson and Johnson, 1996; Bednarz, 2004). Johnson and Johnson (1996) and Bednarz (2004) portend that increased use of ICT in teaching and learning raises a wide variety of issues which are technical, pedagogic, industrial, financial and strategic, for example: effective use of ICT on any significant scale requires new teaching methods, and awareness of effective practices. It requires a further breakdown of the traditional 'private' nature of teaching, and, there is a need for active staff-development programs, greater teaching support (and/or a wider range of non-teaching skills from the staff), e.g. technical support, web developers, and substantial investment may be required in hardware and software. Substantial reworking of capital and recurrent budgets is also likely to be necessary. There may also be a need for student training programs and help-desk facilities. There are access and equity issues for students: e.g. marginalization by certain groups as a result of the reliance on expensive technology. Rewards and incentives to encourage staff to invest substantial time and effort to initial developments, copyright rules, intellectual property and moral rights, equitably managing teaching loads, especially when there is unequal involvement in ICT-based teaching, or the greater capital investment and time often required are other crucial issues (Johnson and Johnson, 1996; Bednarz, 2004; Sang et al., 2010). Even though the recent increase in primary school enrollment has amplified the demand for and access to secondary schools such that there are currently 4000 public secondary schools in Kenya, availability, extent and potential use of computers in teaching and learning is not well documented. This is an inference of minimal and incoherent use of the technology in secondary schools in Kenya. The Kenya Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MOEST) is concerned with the quality of secondary education which is characterized by poor performance in core subjects such as Mathematics and Science. There are several benefits for integrating computers into secondary schools as students in this age need to focus on subject-specific content, greater critical thinking skills as well as scientific inquiry. Students may benefit greatly with the analytical, creative, and collaborative power of computers to map out and analyze assumptions, present ideas, and collaborate in projects with peers from around the country and around the world (MOEST, 2005). As has been observed, in Kenya and subsequently Kisumu, there has been erratic use of computers for educational purposes. The cultural context of ICT adoption, language barriers, and attitudes toward ICT affect the rate at which it is adopted. Perceived difficulty in the integration of ICT in education is based on the belief that technology use is challenging, its implementation requires extra time, technology skills are difficult to learn, and the cost of attaining and maintain resources is prohibitive. Few schools own or have access to computers for teaching and learning. According to Odera (2002), the introduction of Computer Studies as an examinable subject in Kenya could be traced to private commercial colleges that introduced the course for income generation in the early 1990s. Even though there was plummeting popularity of computer courses among students, parents and teachers, there was lack of reciprocal action on the side of the government to increase enrollment and related infrastructure. ICT operators in the Kenyan education field included organizations such as Computer for schools Kenya (CfSK), Kenya ICT Trust Fund, Kenya Computer Initiative 222 Educ. Res. Table 1. Performance in Geography Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) in Kisumu District Year 2009 2008 Enrollment 1272 1184 Mean score 5.019 5.530 Source: Osodo et al. (2010) (KCI), Kenya Education Network (KENET) and others. Such agencies and non-governmental organizations made attempts to provide ICT hardware and software as well as technical services to schools in Kenya in liaison with the government (Krige and Okono, 2007). Be that as it may, the efforts are disjointed and have had little impact in education. This necessitated the study to establish innovative computer uses that would help raise educational standards in the country. The study focused on Kisumu district since it was realized that the performance of Geography in the national examinations was relapsing as indicated in Table 1. From Table 1, it is observable that even though enrollment increased from 1184 in the year 2008 to 1272 in the year 2009, performance in Geography in the national examinations declined. Specific objectives of the study were: 1. To establish availability of computer based resources in Geography education in secondary schools. 2. To assess extent of utilization of computer based resources in Geography education in secondary schools. 3. Assess potential utilization of computer based resources in Geography education in secondary schools. teaching and learning Geography in schools, a Likert type scale on two to five measurement points with nine items was administered to the teachers and students. The respondents were asked to provide information regarding the name of their schools, classes they taught, contact details (optional), whether or not they had computers for teaching Geography and in case computers were used at all or effectively in order to enhance comprehension of concepts. They were also required to indicate potential areas of use of computers in teaching and learning Geography. Validity and reliability of the instruments To ascertain validity of the instruments, items were discussed with three authorities in the content area and their expert opinions were used to determine and ascertain validity of the instruments. Triangulation was also done as a way of reducing uncertainty of interpretation of the results, as a form of cross-checking as recommended by Nkpa (1997). In order to ascertain accuracy and consistency of the instruments with regard to reliability, the testretest reliability procedure was performed as suggested by Osodo et al. (2010). Suter (1998) and Nkpa (1997) also contended that by administering the same instrument again to the same subjects after a time period has elapsed and statistically comparing the results, evidence of reliability would be observed. Subgroups were randomly selected from the normative groups to examine the testretest reliability of the revised questionnaires. The teachers and the learners were then asked to complete check-lists twice over a four week period. The Pearson Product Moment correlation co-efficient on total check-list scores was then determined. The exact agreement method for specific check-list items (agreements on both occurrence and non-occurrence cases divided by the total number of items) was then used to determine the test-retest reliability. The formula used for calculating the reliability coefficient was: r = ∑(X – X) (Y – Y) √[∑(X – X)2 ∑( Y – Y)2] where r is the linear correlation coefficient which measures the strength and the direction of a linear relationship between two variables, X and Y being the two subgroups randomly selected for the test-retest reliability of the instruments. RESEARCH METHODS Venue and Sample Data collection The research was conducted in Kisumu district of Nyanza province, western Kenya. In this study, general population was all secondary school Geography teachers (N=240) and students (N=3,500) in Kisumu district. The study sample was form three secondary school students taking Geography as an examinable subject (n=1,165) as well as form three secondary school Geography teachers (n=80), which constituted 30% of the population selected by simple random sampling technique. The table of random digits was read starting at a random point and each digit that appeared in the table read and recorded to generate the random list of students. From the starting point, the table was read systematically in the downward direction (vertically) and the corresponding members of the population for all the selected numbers used as the random sample. Fraenkel and Wallen (2000) and Suter (1998) recommended this sampling strategy since each member of the target population has an equal and independent chance of being included in the sample. The researcher made advance visits to schools and made appointments with the respondents in their schools then administered the questionnaire within one week after the visit, at the convenience of the respondents. All the 80 teachers and 1165 students responded to the teacher and student questionnaire respectively. Instruments Data collection instrument was student and teacher questionnaire. To investigate the availability and extent of use of computers for Data analysis procedure Frequency counts were computed for the data collected by use of the questionnaire on a two to five point Likert type scale. Mean scores of the respondents on each item of the scale were then calculated. For the five point items, the statements on the Likert scale were scored as follows: ‘Strongly Agree’=5 points, ‘Agree’=4 points, ‘Undecided’=3 points, ‘Disagree’=2 points, ‘Strongly Disagree’=1 point. A mean score of above 3 was interpreted to denote a positive perception, a mean score of 3 denoted a neutral perception and a mean score of below 3 denoted a negative perception. Responses to items from the two point scale were coded and scored as frequencies and mean. Osodo et al. 223 Figure 1. Percentage of schools in Kisumu district that have computers RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Availability of computer based resources Geography education in secondary schools in The first part of this research involved an investigation of the percentage of secondary schools within Kisumu district that had computers. Out of a total number of 80 schools, a paltry 6 (8%) had computers whereas 74 schools (92%) did not have computers (Figure 1) that could be used for Geography teaching and learning. A close scrutiny disclosed that even though computers existed in such schools, there were no clear cut policies on their integration in teaching and learning specific subjects such as Geography. Instead, there was sporadic use of computers for word processing, spreadsheets and other non-academic management purposes. Figure 1 shows that a super majority of schools in Kisumu district did not have computers for use in teaching and learning. From this information, it is apparent that the use of computers in education is either minimal or non existent as corroborated by Demirci, (2009), Kinuthia (2009) and Odera (2002). Kinuthia (2009) and Farrell (2007) contend that very few secondary schools have sufficient ICT tools for teachers and students. Even in schools that have computers, the student-computer ratio is 150:1. Most of the schools with ICT infrastructure have acquired it through initiatives supported by parents, the government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), or other development agencies and the private sector, including the NEPAD electronic school programme. The basic problem is that Kenya lacks adequate connectivity and network infrastructure. Although a small number of schools have direct access to high-speed connectivity through an Internet service provider, generally there is limited penetration of the national physical telecommunication infrastructure into rural and lowincome areas. Consequently, there is limited access to dedicated phone lines and high-speed connectivity for electronic mail and the Internet. Even where access to high-speed connectivity is possible, high costs inhibit access. About 10% of secondary schools with computers are able to share teaching resources via a LAN. As a solution to these access problems, the ministry hopes to leverage the e-government initiative of networking public institutions countrywide to facilitate connectivity for the educational sector (Farrell, 2007). Utilization of computer based resources Geography education in secondary schools in It was apparent from the results (Figure 1) that many schools in Kisumu district did not have computers that could be available for use in teaching and learning Geography. There was paucity of computers in several schools, and, in the few schools where there were computers, they were not used for Geography education, even though they could have been available for such use. Other schools had computers but were a reserve of the school administration, dedicated for record keeping and word processing. As such, it was assumed that such schools did not have computers since they could not be accessed for use in Geography education. Since many schools did not have computers for teaching and learning Geography, introduction of general purpose and curriculum focused software would be difficult unless such schools got access to computers for teaching and learning. As such, performance in certain abstract topics was likely to decline since students and teachers in the schools would not be able to integrate 224 Educ. Res. computers in to the curriculum. The introduction of computer educational packages were likely to have a positive effect in the performance of learners thereby raising educational standards. There are a number of challenges that may face access and use of ICT in Kenya such as high levels of poverty that hinder access to ICT facilities, limited rural electrification and frequent power disruptions. Where there is electricity, there is high cost of internet provision, high costs associated with ICT equipment, infrastructure and support. As a result of such challenges, the use of computer technology in education in Kenya may not be widespread. The Kenya Government’s Ministry of education’s policy on ICT is to integrate ICT education and training into educational systems in order to prepare the learners and staff for the country’s future economy and thereby enhance the nation’s ICT skills (Republic of Kenya, 2005). A survey of 56 schools in seven out of eight provinces in Kenya by Oloo (2009) corroborated these findings that use of computers for teaching and learning in Kenya was dismal with a 7.14% performance. Respondents in schools surveyed by Oloo felt that they did not have adequate funding to purchase ICT equipment and would consider buying them for administrative purposes such as letter typing and examination processing. The priority of most schools surveyed was to acquire computers for administration purposes before anything else (Oloo, 2009). The empirical data collected in Oloo’s survey showed that the range of number of computers owned by schools varied widely from one school to another. In his survey 17.9% of schools (10) had less than 5 computers. 46.4% of schools had 20 or less schools while 62.5% had l30 or fewer computers. Given an average secondary school population of 500 students, this gives a very low student to computer ratio. During this survey it was clear that majority of teachers where ill equipped to effectively integrate ICT in classroom. The main challenge for teachers interviewed was lack of adequate number of computers, educational applications, training, policy and strategy on how integration should be done (Oloo, 2009). A baseline survey report of ICTs in secondary schools in selected parts of Kenya established that administrative use and examination processing was the most frequent followed by teaching of basic computer skills. This was because most schools felt financially constrained and the little money they had would rather be spent on administrative support services. It was also found that a few schools had purchased schools management software which used with varying success. Most felt unsupported with lack of training on sue of management software. The most common modules bought by schools were examination, timetabling and accounting modules (Oloo, 2009). Even though Oloo’s survey indicated some increase in computer use in schools for general purposes, it is observable that integration of computers in teaching and learning specific subjects like Geography is non existent. Potential utilization of computer based resources in Geography education in secondary schools Even though computers have been established to aid teaching and learning, not many institutions use them innovatively. While computers may be common in Geography instruction in higher education, their use at the pre-collegiate level is not very common, but is increasing. The use of computers in education is often termed Computer Assisted Learning (CAL). CAL indicates use of computers as an aid in learning rather than only as a tool for research. Taylor (1991), Fitzpatrick (1990) and Scheffler (1999) suggested a typology for CAL in Geography including computers as sources of data and information; computers as analytical tools; computers as laboratories for investigating the world; computers as instructors. Other potential uses include word processing, database, spreadsheet, tutorials, statistics, data storage and display, communications, simulations, cartography, remote sensing, Geographic Information Systems and the internet. Simulations is touted to be crucial in aiding comprehension of abstract concepts thereby enhancing learners’ performance in Geography. Computer simulations are software applications that include an executable model of a system. The system may either be an actual physical system, or, a theoretical one. Simulations involve the use of a model to conduct experiments which convey an understanding of the behaviour of the system modeled. The act of simulating something generally entails representing certain key characteristics or behaviour of selected physical or abstract system. The computer operator loads as many as possible the potential parameters of a situation in the computer. The computer is then programmed to extrapolate results of any change in the original situation. They can reduce cost, reduce risk and improve understanding of the system under study. CONCLUSIONS AND IMLPICATIONS The study concluded that many schools in Kisumu District did not have computers dedicated for teaching and learning Geography. The few schools that had computers did not use them for Geography education. Instead, there were sporadic and superficial use of computer technology in basic applications for manipulation of figures and text using Microsoft Excel and Microsoft Word. The extent of computer use in Geography education was therefore minimal, if any, uncoordinated and lacking in innovation. As such, students were faced with perennial problems in Osodo et al. 225 comprehending certain abstract topics attributable to lack of computer technology in educational endeavours. Since it was established that hardly any schools owned and used computer technology for geography education, the study recommends that the government should have a clear policy on use of computers in schools so that more schools can incorporate computers in teaching and learning, guided by clear, time tested policies. Also, follow up mechanisms should be put in place by the government to ensure the policies are implemented as stipulated. The government should also zero rate computers and related accessories so that as many schools as possible are able to purchase them. Where poverty levels are high, the government should donate computers to the schools and initiate sustainable computer projects. The study also recommends that teachers should be trained on the use of computers in teaching and learning so that they become competent in using them in teaching. Both pre and in-service teachers should be trained in computer literacy. The government should also provide incentives to students and teachers who make earnest attempts to use computer technology in teaching and learning so that they feel extrinsically and intrinsically motivated. REFERENCES Alexander S, Blight D (1996). Technology in International Education: A Research Paper, (Presented to 10th International Education Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 3 October 1996), Canberra, IDP Education Australia. Alexander S, McKenzie J, Geissinger H (1998). An Evaluation of Information Technology Projects for University Learning, Committee for University Teaching and Staff Development, Canberra. Executive summary at: http://services.canberra.edu.au/CUTSD/announce/ExSumm.html. Downloaded 24/10/2010. Amory A (1997). Integration of technology into education: theories, technology, examples and recommendations, Contract Report, Open Society Foundation of South Africa, Cape Town Open Society Foundation of South Africa, Cape Town. Bednarz SW (2004). Geographic information systems: A tool to support geography and environmental education. GeoJ. 60:191–199. Castleford J (1998). 'Links, lecturing and learning: some issues for geoscience education', Comput. Geosci. (24):73-77. Demirci A (2009). How do Teachers Approach New Technologies: Geography Teachers’ Attitudes towards Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 1(1):43. Duffy T, Cunningham D (1996). Constructivism: Implications for the Design and Delivery of Instruction. In Jonassen D. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. New York: Simon & Schuster. Pp. 1(1): 10-20. Farrell G (2007). Survey of ICT and education in Africa: Kenya country report. In www.infodev.org. Accessed on 18/05/2010. Fitzpatrick C (1990). Computers in geography instruction. J. Geogr. 89(4): 148–149. Fraenkel WS, Wallen NE (2000). How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education. New York: Mc Graw Hill. Government of Kenya (2005). Kisumu District Strategic Plan 2005 2010. Nairobi: Coordination Agency for Population and Development, Ministry of Planning and National Development. Harasim L, Hiltz SR, Teles L, Turof M (1995) Learning Networks: A Field Guide to Teaching and Learning Online, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press. Henning P (1998). Everyday Cognition and Situated Learning. In Jonassen, D. Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 110-125. Johnson DW, Johnson RT (1996) 'Cooperation and the use of technology', in D.H. Jonassen (ed.) Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology, New York, Simon & Schuster Macmillan. pp. 1017-44. Kinuthia W (2009). Educational Development in Kenya and the Role of Information and Communication Technology. International Journal of Education and Development using ICT. 5(2):1-19. Krige K, Okono P (2007). Setting up and sustaining e-learning nd projects. [A paper presented at the 2 International Conference on ICT for development, education and training at Safari Park Hotel on th th May 28 to 30 , 2007]. MOEST 2005, Kenya Education Sector Support Programme: 20052010: Delivering Quality Equitable Education and Training to All Kenyans. Draft 9 May 2005, Nairobi. Nkpa N (1997). Educational research for modern scholars. Enugu: Fourth Dimension. Odera FY (2002). A study of computer integrated education in secondary schools in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Unpublished Ph. D Thesis. University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Oloo LM (2009). Baseline survey report for ICT in secondary schools in selected parts of Kenya: Draft report for Developing Partnership for Higher Education. Nairobi. Osodo J, Indoshi FC, Ongati O (2010). Attitudes of students and teachers towards use of computer technology in Geography education. Educ. Res. 1(5):145-149. Osodo J (1999). 3D Visualization skills incorporation into a Biology undergraduate course, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa. Papastergiou M (2009). Digital game-based learning in high school computer science education: Impact on educational effectiveness and student motivation. Comput. Educ. 52 (1):1-12. Rieber L (2005). Multimedia learning in games, simulations, and microworlds. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning .New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 549-567. Sang G, Valcke M, van Braak J, Tondeur L (2010). Student teachers' thinking processes and ICT integration: Predictors of prospective teaching behaviors with educational technology. Comput. Educ. 54(1): 103-112. Scheffler FL (1999). Computer technology in schools: What teachers should know and be able to do. J. Res. Comput. Educ. 31(3):305– 326. Suter WN (1998). Primer of educational research. London: Allyn. Taylor DRF (1991). Geographic Information Systems: The Microcomputer and Modern Cartography. New York: Pergamon Press. United Kingdom Government (2004). 2004 Report: ICT in schools – the impact of government initiatives: Secondary Geography May 2004. Downloaded on 15/10/2009 from http://www.ofsted.gov.uk. University of Wollongong (1996). Exploring the Nardoo: an imaginary inland river environment to investigate, maintain and improve, Canberra, Interactive Multimedia Pty. Wabuyele L (2006). Computer Use in Kenyan Secondary Schools: Implications for Teacher Professional Development. In C. Crawford et al., Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2006 (pp. 2084-2090). Chesapeake, VA: AACE. Wade W, Hodgkinson K, Smith A, Arfield J (1994). Flexible Learning in Higher Education, London, Kogan Page.