Japan’s Incipient Transformation 30 September 2004 Robert A. Madsen Center for International Studies

advertisement

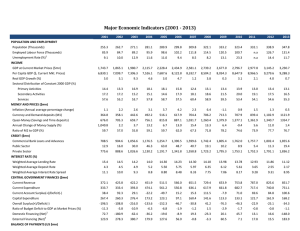

Japan’s Incipient Transformation 30 September 2004 Robert A. Madsen Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Outline 1) The Fundamental Problem of Excess Savings 2) The Consequent Structural Distortions 3) Scenarios for Japan’s Future Economic Evolution 4) Reasons for Cautious Optimism 5) Remaining Risks Conclusion 2 Outline 1) The Fundamental Problem of Excess Savings 2) The Consequent Structural Distortions 3) Scenarios for Japan’s Future Economic Evolution 4) Reasons for Cautious Optimism 5) Remaining Risks Conclusion 3 The Demographic Wave Population Distribution, 2000 Age 100+ 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 Thousands of People Source: National Institute of Population and Social Security Research 4 A Paucity of Profitable Investments Poor Historical Returns Deflation of the 1990s The average real rate of return on bank deposits was negative from 1960 to 1989. Except in the bubble period, the yields generated by household portfolios of stocks and bonds were paltry—often below zero. Only land appreciated dependably from the 1950s through the early 1990s. Since the bubble’s collapse the value of residential real estate has fallen by 60%. According to the Official National Accounts, households lost some Y500 trillion in wealth, or roughly a year’s GDP, over the course of the 1990s. Insufficiency of Retirement Savings Government. corporate pensions are under-funded by well over one year’s GDP. Assuming the current level of household wealth and a life expectancy of 80 years, a typical retiree will have to live on only 24-32% of his pre-retirement income. 5 An Over-Abundance of Capital Gross Savings Rates Percentage of GDP 40 30 77-84 20 85-92 93-98 10 0 Japan Source: International Monetary Fund EU USA 6 Summary The poor rates of return available on household investments aggravated the tendency of middle-aged people to save a high proportion of their income. The consequent, elevated savings rate represented a chronic insufficiency of aggregate demand. This created a deflationary bias that might have driven the country into a deep and prolonged recession — or even a depression. The question, therefore, is not why Japan grew so slowly during the 1990s and early 2000s but rather how it managed to grow as rapidly as it did . . . 7 Outline 1) The Fundamental Problem of Excess Savings 2) The Consequent Structural Distortions 3) Scenarios for Japan’s Future Economic Evolution 4) Reasons for Cautious Optimism 5) Remaining Risks Conclusion 8 Expedient One: Excessive Corporate Investment P e rc e n t a g e o f G D P Corporate Investment 25% 20% Japan 15% US 10% Japan’s Bubble 5% US Technology Bubble Efficient Level 0% 95 90 85 Source: Goldman Sachs 9 Expedient Two: Fiscal Stimulus - 8.0 - 4.0 0.0 2000 1995 1990 1985 Percentage of GDP Government Budget Balance -4.0 Source: Economist Intelligence Unit 10 Combined Contribution to Aggregate Demand Excess Savings Absorbed Percentage of GD P 30% 20% Government Deficit “Excess” Demand 10% Corporate Investment “Sustainable” Demand 0% 85 90 Sources: Goldman Sachs, Economist Intelligence Unit 95 0 11 Summary From the middle 1980s through the early 2000s Japan resorted to various expedients to compensate for the weakness of adequate demand, including: A large current account surplus Excessive corporate investment in plant and equipment Huge government budget deficits Unfortunately, these expedients damaged the economy by depressing efficiency and profitability and by driving up the national debt. Since the corporate and government sectors could not expand much further relative to GDP, Japan must sooner or later find new sources of growth . . . 12 Outline 1) The Fundamental Problem of Excess Savings 2) The Consequent Structural Distortions 3) Scenarios for Japan’s Future Economic Evolution 4) Reasons for Cautious Optimism 5) Remaining Risks Conclusion 13 Overview of Three Scenarios Scenario One: Lowering the Savings Rate Scenario Two: Exporting Excess Savings Scenario Three: Continuation of the Status Quo 14 Scenario One: Lowering the Savings Rate Return to Typical Balance This could occur through aggressive structural reforms, which would transfer more wealth to households and enable them to curtail their savings; or it could happen spontaneously, through an exogenous change in household financial behavior. Percentage of GDP 40% 30% 20% Net Trade 10% 0% 10 5 0 95 90 85 Source: Goldman Sachs, Economist Intelligence Unit, National Accounts Government Deficit Corporate Investment 15 Scenario Two: Exporting Excess Savings P e rc e n t a g e o f G D P New "Sustainable" Demand 30% Net Trade New Demand 20% Government Deficit Corporate Investment 10% 0% 10 5 0 95 90 85 Source: Goldman Sachs, Economist Intelligence Unit, National Accounts 16 Scenario Three: Continuation of the Status Quo Further Structural Damage Percentage of GDP 30% Larger National Debt 20% Government Deficit Greater Corporate Inefficiency Corporate Investment 10% 0% 10 5 0 95 90 85 Sources: Goldman Sachs, Economist Intelligence Unit 17 Summary Japan could continue as it has, relying on inordinate corporate investment and government deficits to absorb its surplus capital, but doing so would eventually depress profitability while also causing the national debt to expand indefinitely. A long-term solution must therefore include curtailing savings, dramatically increasing net exports, or some combination of both. If there are economic or diplomatic reasons why the current account surplus cannot double or triple in size, then the only way forward is through a sharp contraction in private-sector savings. 18 Outline 1) The Fundamental Problem of Excess Savings 2) The Consequent Structural Distortions 3) Scenarios for Japan’s Future Economic Evolution 4) Reasons for Cautious Optimism 5) Remaining Risks Conclusion 19 The Ideal Trajectory Greater Consumption and Net Trade Percentage of GDP 30% 20% Net Trade Government Deficit Corporate Investment 10% 0% 10 5 0 95 90 85 Source: Goldman Sachs, Economist Intelligence Unit, National Accounts 20 The Nature of the Present Recovery 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 Source: Cabinet Office Trade Government Investment Consumption 1999 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 1998 P ercent G D P G ro w th Contributions to Economic Growth Note that the deflators for investment and perhaps consumption overstate growth. 21 The Promise of Less Supply, More Demand Household Surplus 10 5 0 2003 2000 1997 1994 Source: BOJ 1991 -5 1988 1985 P e rc e n t a g e o f G D P 15 22 A Muddied Picture Private-Sector Surpluses 5 Household Savings Corporate Savings 0 2000 1995 1990 -5 1985 Percen tag e o f G D P 10 -10 Source: BOJ 23 The Continuing Financial Imbalance 15 10 5 Household Savings Corporate Savings 0 2003 2000 1997 Source: BOJ 1994 -10 1991 -5 1988 1985 P e rc e n t a g e o f G D P Countervailing Government Demand Government Deficit 24 The Probable Trajectory Reluctant Adjustment Percentage of GDP 40% Net Trade 30% Government Deficit Corporate Investment 20% 10% 0% 10 5 0 95 90 85 Sources: Goldman Sachs, Economist Intelligence Unit 25 Japan Transformed Real GDP Growth 6 Inadequate Demand 5 Inadequate Supply Percentage 3 2 Current Account Deficits? Return of Inflation? 4 1 0 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 Source: Economist Intelligence Unit 2007 Official Figures 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 -2 2000 -1 Adjusted Deflators 26 Summary The present recovery began as a typical Japanese upturn, stemming from overseas—and particularly Chinese—demand. One quarter of the growth derived from Improved net exports. One half of the growth comprised greater corporate investment, much designed to serve overseas markets. The recent, sharp decline in household savings, however, gives reason to hope that aggregate supply and demand may soon come back into balance. Paradoxically, the likely failure of the government to implement aggressive structural reforms enhances the probability of this desirable outcome; with domestic demand stronger, and GDP rising faster, than would otherwise be the case. The output gap could close as early as the end of 2006, transforming Japan from a country with chronically inadequate aggregate demand into a more typical economy whose growth potential is limited by supply-side constraints. 27 Outline 1) The Fundamental Problem of Excess Savings 2) The Consequent Structural Distortions 3) Scenarios for Japan’s Future Economic Evolution 4) Reasons for Cautious Optimism 5) Remaining Risks Conclusion 28 Short-term Risk: Stalled Recovery Domestic Factors Investment falls too sharply Consumption stagnates Potential Impact Several points of GDP One or two points of GDP International Factors China experiences “hard landing” US growth rate falls precipitously Oil price surges 0.5-0.9% of GDP directly, 1.0-2.0% indirectly Less than China Consequences Some combination of adverse developments could conceivably kill the recovery and cause a reversion to Japan’s recent pattern of inadequate aggregate demand and deflation. 0.3-0.4% of GDP for every sustained $10 per barrel increase 29 Long-Term Risk: National Debt Net Debt Gross Debt Size 7070-90% of GDP 165% of GDP Analysis Gross debt minus assets Asset values overstated Loans between central, local govts. govts. Pension assets BOJ holdings of JGBs Book values sometimes deceptive Many assets illiquid Political constraints on local loans, BOJ holdings Liabilities understated FILP generally ignored Other accounts ignored Disallow contingent liabilities Bank recapitalizations Insurance company recapitalizations Pension shortfalls Implications Debt is low Interest rates will remain low No danger of crisis Contingencies critically important Bank, insurance costs are public Pensions must be paid in part Debt is high Rates could rise gradually or sharply Danger of crisis in 2010s or later 30 Fiscal Consolidation (I) 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 -7 -8 -9 1998 Percentage of GDP Budget Deficit Trajectory Projections Basic Scenario Reform Scenario Source: Economist Intelligence Unit 31 Fiscal Consolidation (II) National Debt Trajectory Percentage of GDP 225 200 175 150 125 Projections 100 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 Basic Scenario Reform Scenario Source: Economist Intelligence Unit 32 Summary Japan could still stumble back into deflationary circumstances. A combination of adverse international developments Sudden, sharp decrease in corporate investment Premature fiscal tightening like that of 1997 Regression is also possible in the medium term if corporate investment continues at such a high level that it creates vast overcapacity like that of the 1990s while also depressing the returns available to workers and investors. If those short- and medium-term obstacles are safely overcome, the biggest long-term challenge is redressing the government’s finances before they become vulnerable to possible spikes in interest rates. Ultimately this is a political question: will the government avoid premature tax increases for a few years but then brave voters’ wrath by hiking them sharply enough to eliminate the budget deficit relatively rapidly? 33 Outline 1) The Fundamental Problem of Excess Savings 2) The Consequent Structural Distortions 3) Scenarios for Japan’s Future Economic Evolution 4) Reasons for Cautious Optimism 5) Remaining Risks Conclusion 34 Conclusion Japan’s slump may well be over. The country may soon look very different than in the recent past. After the output gap closes the country’s trend growth rate will fall to 1.0-1.5% per annum. Elevating the sustainable rate above that level will require big cuts in capital investment and probably more immigration. The focus of political debate will ultimately shift to the national debt. Inflation begins in perhaps early 2007. Inflation ameliorates many of the stresses in the banking system, lightens the burden of household and corporate debt. The current account very slowly moves from surplus towards deficit. By the early 2010s foreigners are providing more of the capital necessary to fund the debt. The challenge would no longer be bolstering demand but rather overcoming the more usual supply-side constraints. External demand brings positive impetus in the short term. Higher consumption and lower savings, though, are far more important. Due to the confidence problem, fiscal retrenchment makes no sense until at least 2007. Greater healthcare and pension costs then render spending cuts impractical, so the key is big tax increases—perhaps raising annual government revenues by 6-9% of GDP by 2012 or 2015. Ultimately both of the big tasks—moderately faster growth and fiscal retrenchment— depend critically on the quality of Japan’s elected leadership. 35 36