Western hindutva: Hindu nationalism in the United Kingdom and North America

advertisement

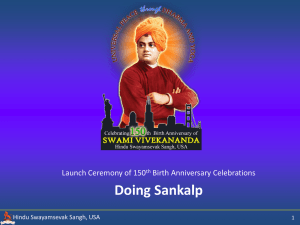

Western hindutva: Hindu nationalism in the United Kingdom and North America Christophe Jaffrelot and Ingrid Therwath Introduction The “long distance nationalism” of diasporas is generally attributed to the nostalgia of these communities for their original homeland. Benedict Anderson, who coined this expression, even suggested that a nearly automatic allegiance binds members of an ethnic diaspora to its homeland1 . However, the context of the host society often plays a crucial role in the birth of such nationalisms. The specific combination of multiculturalism and racism that can be found in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada has been particularly conducive to this form of identity politics: it has not only made it possible – or even legitimate – but it has also fostered this form of ethnic mobilisation. Indeed, in these three countries, multiculturalism has enhanced the role and status of community leaders and has emphasized communitarianism through affirmative action and the introduction of quotas for example. The implementation of these policies has coincided with the rise of racism, which further reinforced community-based visions of society and politics. The roots of long-distance nationalism can be traced to this very particular conjunction in the host countries. However, this approach still ignores the impact of ideology-driven movements which are usually based in the mother-country but whose networks spread over vast territories. The Hindu nationalist movement illustrates this. Its activities outside India have only recently been brought to light in the wake of the 2002 events in Gujarat although the Sangh Parivar had been developing several of its offshoots abroad over the last thirty years. Far from being instilled by sheer nostalgia in a favourable context, Hindu nationalism in the West is a carefully crafted graft elaborated in the motherland and then methodically spread around the world to serve ideological and strategic purposes. The careful engineering of the RSS’s global presence thus sheds a new light on the dynamics of long-distance nationalism and points out to the continuing domination of a central authority. 1 . Benedict Anderson, The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World, London/New York, Verso, 1998, p. 74. 1 Multiculturalism cum racism: the recipe for diasporic nationalism? If Hindu nationalist organizations have made real, albeit relative, progress in Great Britain and in North America, it is because combine a certain amount of ordinary racism and a strong sense of multiculturalism can be found in both areas, as Sucheta Mazumdar suggested in her seminal work on the United States2. In this country multiculturalism has encouraged the organization of the Indian minority, initially through the affirmative action policies. In 1977 the Association of Indians America succeeded in having Indians registered as a ‘minority’ in order to benefit from affirmative action programs provided by the state. In 1982, the US Small Business Administration accepted a petition from the National Association of Asian Indian Descent requesting that Indians be recognized as a “socially disadvantaged minority in need of special preferences.” In 2000, the United States census also enabled Indians to register as a specific and separate category which made it possible for them to dissociate themselves from Pakistanis and to benefit from new concessions: “Once included as minorities under the rubric of Asian Americans, they [the Indians] have been able to take advantage of new legislation providing for small-business loans to minorities, antidiscrimination legislation in housing, commissions for tracking hate crimes, affirmative action hiring programs in companies, and so on”3. Given the “increase in overt religiosity in American political life”, Hindus in the US were also allowed to build temples which proliferated thanks to taxdeductible contributions4. While the State promotes multiculturalism, various forms of discrimination exists in British, American and Canadian societies. Of course, one has to differentiate between the xenophobia of extreme rightwing movements and more frequent expressions of ordinary racism. Bhatt and Mukta point out that "the American and British New Right language of the 1980s [...] carried similar themes of ‘majority discrimination’ and an attack on minority rights and protection.”5 And thus Senator Pat Robertson slammed Hinduism, which he described as diabolical in the context of a campaign aiming to reduce the flow of Indian immigrants in a “dominantly Christian” country. Children are the first victims of this refusal of otherness. Many second-generation immigrants in primary or secondary school have been insulted because of the color of their skin but also of Hindu customs such as vegetarianism, cow worship, arranged marriages, wearing saris or the upper caste men’s sacred rope. This cultural context explains the founding of Hindu defense organizations such as the United States the Federation of Hindu Associations which vehemently protested against Sony’s and Gap’s use of Hindu deities in their advertising campaigns. Both companies had to cancel the ads and apologize for them. Similar protests were leveled at the American series The Simpsons, after one of the show’s characters threw peanuts at a statue called Goofy Ganesh.6 The scale of this kind of challenges prompted Hindu nationalists to create the 2 Sucheta Mazumdar, “The Politics of Religion and National Origin: Rediscovering Hindu Indian Identity in the United States”, in V. Rairkar and S. Mazumdar (eds), Antinomies of Modernity. Essays on Race, Orient, Nation, Duke, Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 223-260. 3 Ibid., p. 241. 4 Ibid., p. 242. 5 Chetan Bhatt and Parita Mukta, Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 23, n° 3, May 2000, p. 437. 6 A. Rajagopal, “Hindu Nationalism in the US: Changing Configurations of Political Practice,” Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 23, no. 3, May 2000, p. 478. 2 American Hindu Anti-Defamation Coalition (ADHADC) in 1997, modeled after the AntiDefamation League, an organization initially founded to combat anti-Semitism. The primary aim of the ADHADC is to monitor the media and make sure iconography and vocabulary used in relation to Hinduism does not convey any prejudice against it. This approach was only possible because American law – in keeping with official multiculturalism – recognizes everything Hindu as worth protecting. Across the border, several organizations such as Canadian Hope and the Hindu Conference of Canada pride themselves in monitoring and protecting the image of Hindus in the national media.7 The Hindu Conference of Canada also aims at increasing the number of visas granted to Indians and helping Indian and Hindu managers practice thanks to degree equivalences. Moreover, it publicly backed the conservative party in the 2006 federal elections.8 This example shows that multiculturalism enables communitarian defense groups to form, which quickly turn into ethnic lobbies. In Britain, the Shilpa Shetty affair was very revealing of the benign form of racism from which Indians are suffering. In January 2007 Shilpa Shetty, a Bollywood starlet, was invited to Celebrity Big Brother, a reality show aired by Channel Four and which consists in locking together so-called celebrities for four weeks and asking the public to vote and eliminate them. Things turned sour when, after three weeks, the three white celebrities turned against Shilpa Shetty, criticizing her diet – she cooked with onions as any Indian does saying that she actually longed to be white since she bleached her facial hair etc. More than 40,000 complaints about racism were sent to Channel Four, mostly by Indians, and Ken Livingston and Gordon Brown had to apologize publicly. Certainly, the very specific context of multiculturalism cum racism that one finds in UK, the US and Canada has prepared the ground for the development of Hindu nationalism. But the impact of well thought out strategies implemented by the Sangh Parivar from India must not be overlooked. A network engineered in, and managed from India The Hindu nationalist activities which attracted a great deal of attention recently pertain to fund-raising. Much is at stake there because of the economic success of the Hindus in the US and, to a lesser extent, in UK. The 2000 US census showed that Indians and Indian Americans – most of whom are Hindus – earned about 67 000 dollars a year, whereas the rest of the population earned about 30 000 dollars as an average. The success story of HinduAmericans made them a priority target of the Sangh Parivar’s fund-raisers, as evident from the 1989 Ram shilas movement onwards. At that time, bricks (shilas) bearing the name of American or British cities were sent – along with generous donations – by the local branches of the VHP to Ayodhya in order to build a new Ram temple. Since then, the inflow of money from abroad has become a major financial resource for the Sangh Parivar in India. Recently, secular NGOs, including AWAAZ, have been able to expose these connections. Their first report, in 2002, dealt with the India Development and Relief Fund (IDRF) in the US and the second one, in 2004, In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism, exposed the UK- 7 Canadian Hope website: http://www.canadianhope.org/aboutus.html 8 Site de la la Hindu Conference of Canada: http://www.hccanada.com/media/HCCEndorsement.pdf 3 based so-called philanthropic organisation, Sewa.9 Both reports have shown that organisations which presented themselves as social work-oriented were in fact closely related to the Sangh Parivar and financed its projects and helped propagate the Hindutva ideology in tribal areas and Dalit slums. So far, no report has been made on the situation prevailing in Canada so far, however Sewa International (also known as Sewa Canada) is working along the same pattern in this country too.10 However, besides fund-raising, the Sangh Parivar has also set up purely ideology-based activities among the diaspora. The Sangh parivar: a global network According to the official RSS history, the first shakha to have been created outside of India formed spontaneously in 1946 aboard a ship linking Bombay to Mombasa in Kenya: One evening, on a tempestuous day, two passengers, both in Khaki [sic] shorts, accidentally met on the deck of the ship. One of them was from Punjab and the other from Gujarat, both unknown to each other. But a popular Hindi song that one of them was singing sotto voce, attracted the other towards him with raised eyebrows; and they recognised each other as belonging to the common Sangh family. Facing towards the Motherland, both of them together then sang ‘Namaste Sada Vatsale Matrubhoome’ [Hail to Thee O Motherland!]. Thus was born the first Sangh shakha off-shore!11 Kenya was indeed the country in which the first non-Indian shakha was officially created in 1947 by these swayamsevaks once they located other Hindus there. Kenya and Uganda were the host countries for Indian immigration in which the RSS expanded the most rapidly in the 1950s and 60s under the label of Bharatiya Swayamsevak Sangh (Indian Volunteer Corps).12 These East African beginnings are not irrelevant to our comprehension of the development of the Sangh Parivar in the West, because many full time cadres that would operate in Great Britain and North America first went through Uganda or Kenya, which they often had to forcibly leave in the 1960-1970s. The African experience of nearly one-quarter of the Hindu community living in Great Britain has considerably influenced British Hinduism and has given it a strong diasporic dimension. The same African and Caribbean detour can be found among many Canadian Hindutva adherents. One of the RSS leaders, M.S. Golwalkar – who headed the movement from 1940 to 1973 – in fact devoted an entire passage of his famous book, Bunch of thoughts, to overseas Hindus, calling on them to act as ambassadors for their nation. 13 According to him, Hindu 9 The Foreign Exchange of Hate : IDRF and the American Founding of Hindutva, Bombay: Sabrang Communications Private Limited, Paris: The South Asia Citizens Web, 20 novembre 2002, www.stopfundinghate.com 10 Jayant Lele, « Indian Diaspora’s Long-Distance Nationalism : The Rise and Proliferation of ‘Hindutva’ in Canada », pp. 66-119, in Sushma J. Varma and Radhika Seshan (ed.), Fractured Identity. The Indian Diaspora in Canada, New Delhi : Rawat Publications, 2003 : p. 101. 11 Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Widening Horizons, New Delhi,Suruchi Prakashan, 1992, p. 1. 12 Chetan Bhatt, “Dharmo rakshati rakshitah: Hindutva movement in UK,” Ethnic and racial studies, vol. 23, no. 3, May 2000, p. 577. 13 M.S. Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, Bangalore, Jagarana Prakashana, 1980 [1966], p 450. 4 migrants should serve "the Cause" abroad. 14 Golwalkar recommended Hindu migrants to teach their children Hindu civilization, to build temples and not to alienate the host society. His successor, Balasaheb Deoras, went even further when, in a 1989 speech, he entrusted diaspora Hindus with part of the RSS mission .15 The RSS thus gradually wished to rely on Hindu communities abroad to spread its message and created a special unit, the Antar Rashtriya Sahayog Parishad (ARSP- Indian Council for International Co-operation), to that effect in 1978. However, the emphasis on the diaspora did not gained momentum until the following decade, at the time when Hindu migrants, mostly in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada started accumulating wealth and influence. At the beginning of this century, there were 552 421, 1 million, and 297 200 Hindus in these three countries respectively. The American politics of emigration quotas in the 1960s enabled many Indian students and qualified workers to settle in the United States and distinguish themselves in higxh earning sectors like the information technologies. According the 2000 US census, the average per capita income in the Indian community was more than twice that of the rest of the population – and most of these Indian emigrants are Hindus. In the United Kingdom, Hindus have become an important local political force thanks to their concentration in certain areas. For instance, 14.7% of the inhabitants of Leicester, 19.6% of those of Harrow, 17.2% of those of Brent are Hindus. 4.1 % of Londoners are Hindus, about four times more than the overall national figure. As for Canada, the 2001 census indicates that 217 000 of the 297,200 Canadian Hindus live in the Ontario province, mostly in the Toronto area.16 Considering this critical mass and the accumulated wealth of these communities, it is only natural that the Sangh Parivar focused primarily on the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. The RSS’s strategy of reaching out to the Hindus in these countries consisted in reproducing the modus operandi of the organization in India. This fact sheds a new light on Benedict Anderson's theory outlined under the ingenious expression of "long-distance nationalism". Anderson suggests that a strong and nearly automatic allegiance binds members of an ethnic diaspora to their homeland.17 The only specific feature that he recognizes in this variant of nationalism has to do with its irresponsibility, which sanctions extreme radicalism. In our opinion, the main weakness of this approach lies in the indifference it manifests with respect to nationalist organizations operating in the homeland that attempt to mobilize its offspring abroad. In fact, "long-distance nationalism" is at least as much the product of a reverse flow, thanks to political entrepreneurs from the mainland fueling nationalist vocations among the diaspora. In the case of Hindu nationalism, the Sangh Parivar was seconded by the Indian State in the propagation of its agenda, which only further reinforced the spread of Hindutva from centre to periphery when the BJP came to powering in New Delhi 1998. The 14 Ibid., p. 456. 15 Cited in H.V. Seshadri, Hindus Abroad: Dilemma – Dollar or Dharma?, New Delhi, Suruchi Prakashan, 1990, p. 13. 16 Office for National Statistics. Commission for Racial Equality, « Focus on religion folder », Census 2001, avril 2001, http://www.cre.gov.uk/research/statistics_census2001pt1.html. Terrance J. Reeves, Claudette E. Bennett, « We the People : Asians in the United States », Census 2000 Special Reports, numéro 17, Decembre 2004, see the web site of the U.S. Census Bureau : http://www.census.gov ; 2001 Census - Statistics Canada, « Selected Religions, for Canada, Provinces and Territories – 20% Sample Data », Religions in Canada: Highlight Tables, 2004, see http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/products/highlight/Religion/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo=PR&View=1a& Code=01&Table=1&StartRec=1&Sort=2&B1=01&B2=All 17 Benedict Anderson, “The New World Disorder”, New Left Review, Mai/Juin 1992 (193), pp. 4-11. 5 Hindu diaspora became a target and a major resource for the ruling party. It appeared not only as a bridgehead in the RSS millenarist mission or, more prosaically, a source of funding, but also a source of influence, a lever for Indian diplomacy through ethno-religious lobbies mostly operating in Washington. Now, regardless of which party is in power, the Indian state has thus become a party to the rise of the Hindu diaspora’s “long distance nationalism” and is often inclined to tap hindutva networks created abroad by the RSS. A variety of mirror organizations In India, the RSS has opened a variety of specialised branches that it still federates and controls. Over the years, this highly centralised system was replicated to the countries where the diaspora had come to settle. This process started only two decades after the birth of the mother organisation in India and, officially since the 2nd of July 1966, the RSS has been operating in Great Britain, as the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (The Hindu Volunteers Corps) 18 . In the following years, the RSS opened HSS outfits in the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Trinidad and Hong Kong. To begin with, the HSS gave absolute priority to multiplying the number of shakhas, as the RSS had done in the years from 1925 to 1948. In Great Britain shakhas were thus rapidly created in cities such as Birmingham and Bradford where they attracted Hindu immigrants eager to convey Hindu culture to their children.19 The HSS took on new importance in the eyes of the "mother organization” during the Emergency in 1975 to 1977. During these 18 months, the RSS was banned for the second time in its history (the first dated back to 1948, following the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi by a former movement member). Its international affiliates proved to be very valuable advocates of its cause and provide an alternative source of funding. The RSS headquarters in Nagpur kept a secret register of swayamsevaks who had applied to emigrate, putting them in contact with those already settled in the destination country and encouraging them to join a shakha or to start one.20 In 1976, swayamsevaks settled in Great Britain founded the Friends of India Society, International (FISI) whose primary aim was to organize pro-hindutva militants and propagate the Sangh’s ideology abroad while exposing Indira Gandhi’s undemocratic suspension of civil liberties.21 Like the RSS in India, the HSS in the United Kingdom adopted a centralized structure with geographic sections headed by a movement cadre. The highest leadership council of the HSS, the Akhil UK Pratinidhi Sabha (a copy of the Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha – Delegate Assembly of All India) and the Kendriya Karyakari Mandal (Central Executive Committee) meet on the same regular basis as their Indian counterparts. Moreover, the HSS holds annual training camps for the movement cadres, exactly like the RSS does in India. Instructors’ Training Camps are meant for for shakha leaders, Officers’ Training Camps for those of a higher rank. These weeklong camps convey the content of the "teachings" to be delivered daily in the shakhas. The fact that emissaries are regularly sent from Nagpur to 18 See the HSS website: http://hssworld.org/index.html 19 Stacey Burlet, « Re-awakenings ? Hindu Nationalism Goes Global », pp. 1-18, IN STARRS, Roy (ed), Asian Nationalism in the Age of Globalization, Japan Library (Curzon Press), Richmond, Surrey, 2001, p. 13. 20 D.R. Goyal, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, New Delhi, Radhakrishna Prakashan, 1979, p. 106, note 91. 21 Walter K Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle, The Brotherhood in Saffron: The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Hindu Revivalism, Westview Special Studies on South and Southeast Asia, Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 1987, pp. 212-3. 6 oversee the camps, or even to hold standard training sessions strengthens the duplication of the RSS modus operandi.22 Furthermore, since the 1980s, the HSS has strived to internationalize Indian issues and mobilize its members for the contruction of the Ram temple in Ayodhya for instance. For the HSS, India is the Matrubhoomi, the "motherland" while the country of residence is merely the Karmabhoomi, le "land of earthly occupations". Just like the RSS which, after having created a network of shakhas, gave rise to a multitude of affiliates forming a so-called family – the Sangh Parivar –, the HSS directly created or at least formally headed a network of sister organizations over the years. The Vishva Hindu Parishad UK was founded some eight years after the VHP in India.23 The Overseas Friends of the Bharatiya Janata Party (OFBJP) became the correspondent for the BJP outside India. The Rashtriya Sevika Samiti (Committee of the female servants of the nation) – the women wing of the RSS founded in 1936 in India - also has an mirror organization in Great Britain, while the main Hindu student Union in Great Britain, the National Hindu Students Forum (NHSF), is the official correspondent for the ABVP. 24 Lastly, Bharat Sewa (Service of India) is the functional British equivalent of the RSS affiliate devoted to social work, Sewa Bharti. This mirror structure can also be found in the United States and in Canada, with only small variations. For instance, the American equivalent of Sewa Bharti is called the India Development and Relief Fund (IDRF), and that of the ABVP is called Hindu Students Council (HSC). The VHP’s effort to unify diasporic Hinduism uses some of the methods employed in India: this involves the construction of "Pan Hindu temples" destined to welcome all sects and castes and the organization of Dharma Sansad (Dharma parliaments) throughout the world. 25 These temples, like the Hindu Unity Temple in Dallas, combine Indian Northern and Southern archictural features and display deities belonging to different traditions of Hindusim. Similar places of worship had been built in India, with the Hindu Rashtra Mandir (Hindu Nation Temple) and the Bharat Mata Mandir (Mother India Temple) in Hardwar. In a similar spirit, the Dharma Sansads bring together Hindu religious figures that have come from local ashrams and temples and who strive to establish and disseminate a Hindu code of conduct by inventing a sort of catechism in an inclusive way. Like in India, the British, American and Canadian branches of the VHP also hold huge rallies in the form of ethno-religious events. The first such gathering was probably the Virat Hindu Sammelan (Great Hindu Assembly) which took place in Milton Keynes, in the suburbs of London, in 1989. For the first time in Great Britain the VHP had managed to bring together hundreds of Hindu organizations (officially 300) and from 50 to 100,000 participants. In United States an even larger rally took place in 1993 to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the arrival of Vivekananda – a religious reformer with nationalist leanings - in Chicago and his famous speech to the world parliament of religions in 1893 in which he had criticized the materialistic West and praised the virtues of a spiritual Orient. This gathering was called "Global Vision 2000," which was an apt reflection of the international ambitions of Hindutva adherents. 22 The founding of the VHP Overseas (led by BK Modi, also president of VHP India) in November 2002 to coordinate VHP activities throughout the world fits within this same logic. 23 C. Bhatt, “Dharmo rakshati rakshitah: Hindutva movement in UK”, Ethnic and racial studies, vol. 23, n° 3, May 2000, p. 559. 25 For more on the VHP, C. Jaffrelot, «The Vishva Hindu Parishad : Structures and Strategies» in Jeff Haynes (ed.), Religion, Globalization and Political Culture in the Third World, Londres, Macmillan, 1999, pp. 191-212 and -« The Vishva Hindu Parishad : A Nationalist but Mimetic Attempt at Federating the Hindu Sects », in Dalmia (Vasudha), Malinar (Angelika) et Christof (Martin) eds, Charisma and Canon. Essays on the Religious History of the Indian Subcontinent, Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2001, pp. 388-411. 7 The main difference between the Sangh’s replicated network in the United Kingdom and the United States is that that the first organization to have been created on American soil was not the local equivalent of the RSS but the Vishva Hindu Parishad of America, which is completely atypical. The VHP-A was founded in 1971 when an important wave of qualified Indians started to emigrate in the United States and it is today is one of the most active branches of the Sangh abroad with 40 operational sub-branches and over 10,000 members.26 Canada followed the same path as the United States. VHP-Canada was created in 1970 and built a temple in Vancouver the following year. It was only later, in 1973 on the recommendation of M.S. Golwalkar that L.M. Sabherwal, an RSS member since his youth who had arrived in Canada in the early 1970s, founded the HSS (initially under the name of Bharatiya Swayamsevak Sangh).27 The Sangh Parivar has thus managed to duplicate its structure abroad. However, the different HSSs, although at the helm of each countries local Sangh Parivar organization, are subjected to RSS policies in India, while the VHP center in Delhi exercises its jurisdiction over its different foreign outfits. Eventually all Hindu nationalist movement affiliates either in India or abroad swear allegiance and report to the same decision-making center, the RSS, which divided the world into geographical areas and assigned each one to a senior cadre.28 In short, the overseas components of the Sangh Parivar look for their material and ideological leadership nowhere but in the motherland. However, the translation of the Sangh’s structure abroad entailed some ideological and operational changes in order to take into account the newly Westernized sensibilities of the diaspora and to render the entire organization more efficient and acceptable to the host States. Strategies in adaptation: the specifities of Western Hindutva From shakhas to the Internet and modern mandirs: reinventing the traditional modus operandi Certainly, Hindu nationalists have retained many features of the original modus operandi of the Sangh Parivar – such as the shakha system and massive mobilisation campaigns -, but they also developed many specific traits. In the shakhas, collective prayers are not so prominent and martial arts have been replaced by collective games. Shakhas welcome women as well as men and they do not necessarily take place every morning and/or every evening, but on Sundays and during holidays. More importantly, while the core ideology of Hindu nationalism has not been diluted, homosexuality, divorce and pre-marital sex have sometimes gained a legitimacy they still lack in India. The HSS has not only adapted the modus operandi of the shakhas, but it has also, supplemented them by alternative techniques. In order to be in tune with the sophisticated means of communication of the high-tech Indian bourgeoisie in the US, it has invented the cybershakha. The first one was inaugurated in September 1999 in New Delhi by Rajendra Singh during a ceremony in which hundreds of swayamsevaks from all over the world took 26 See the VHP website: http://www.VHP.org/englishsite/d.Dimensions_of_VHP/qVishwa%20Samanvya/vishvahinduparishadabroad.ht m 27 Ajit Jain, “Genesis and Growth of HSS in Canada,” India Abroad, May 1, 1998, p. 19. 28 AWAAZ- South Asia Watch Limited, In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism, 2004, http://www.awaazsaw.org/ibf/index.htm: p. 46. 8 part.29 In addition to these cybershakhas, the Sangh Parivar has resorted to a great number of websites in order to reach its members and sympathisers and let them avail of its take on current events on a daily basis. In the US, the most important of these websites is probably the Global Hindu Electronic Network (GHEN, www.hindunet.org) which was launched in 1996 by the HSC and the VHP-A. But the more radical one is undoubtedly Sword of Truth (www.swordoftruth.com) which constantly updates a black list of anti-Hindu personalities. These sites also provide answers to issues that concern the Hindu diaspora in pages entitled « Eternal Hindu Values » or « Hindu Custom » for instance. Besides this reinvention of the shakha, the most obvious adaptation in the Sangh Parivar’s modus operandi lies in the prominent part played by religious leaders. The very fact that the VHP-A and the VHP Canada existed even before RSS shakhas were set up in the US and in Canada is a consequence of this. This specificity stems from the long history of Hindu religious movements in the West. Indeed, the Sangh Parivar relied heavily on the support of half a dozens well-established sampradayas (religious traditions or currents): the Arya Samaj, a socio-religious reformist movement that was founded in 1875 by Swami Dayanand Saraswati, the Ramakrishna Mission, founded in 1897 by Swami Vivekananda, the Divine Life Society created in 1936 by Swami Shivananda, the Chinmaya Mission founded in 1953 by Swami Chinmayanand (one of the founding fathers of the VHP), the Sri Aurobindo Society initiated in 1960 and the International Sai Organization established in 1972 by Sathya Sai Baba. The popularity of these organisations amongst the Hindu diaspora in the US is a reflection of the ground work of Hindu swamis and gurus overseas. In UK, the Swaminarayan movement offers the most significant religious platform for the Sangh Parivar.30 Contrary to what Williams suggests31, this sampradaya, which developed in West India – especially in Gujarat – from the early XXth century onwards, has affinities with Hindu nationalism. It displays remarkable organisational skills – as is evident from the mass meetings which celebrated the bi-centenary of its founder in Ahmedabad in 198132 – and, more importantly, it has made serious efforts for standardising Hinduism. It has defined a corpus, called « canon », which calls to mind the VHP’s attempts at crystallising a Hindu catechism.33 Born in Gujarat, the Swaminarayan movement has spread all over the world in the wake of the gujarati diaspora, first in South and West Africa, and then in UK when Indians had to flee Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda after these countries became independent and implemented anti-Indian policies in the 1960s-1970s. The movement’s attractiveness grew quickly after 1970 when its leader, Yogiji Maharaj, went to Taroro (Uganda) to inaugurate temples and then in England where he established the Islington temple in the suburb of London on 14 June 1970. He was the first leader of the Swaminarayan movement who travelled in such a manner and decided to repeat his international tours in order to give a global dimension to his sampradaya. This process reached its climax in 1995 with the opening of the huge temple of Neasden near 29 The Organiser, 10 octobre 1999. 30 See R.B. Williams, A New Face Of Hinduism - The Swaminarayan Religion, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984 and An Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. 31 Ibid., p. 234. 32 Ibid., p. 177. 33 Ibid., p. 184. 9 London. This place of worship, which is visited by 450 000 devotees yearly34, has become a crucible of Hindu nationalism. It propagates the same kind of ideology and the same personalities are often involved in both organisations. Besides the Swaminarayan movement, the gujarati milieu has contributed to the development of Hindu nationalism in many different ways. Radio Sunrise, a property of the Hinduja family, two daily newspapers, Garavi Gujarat and Gujarat Samachar and a magazine, Asian Voice which belongs to C.M. Patel (a leading member of the Swaminarayan movement), have played a major part in projecting a Hindu-centred image of the Gujarati community in Britain.35 This trend has gained momentum when Gujarat became a stronghold of the Sangh Parivar. The above-mentioned newspapers, for instance, have echoed the views of Narendra Modi (the leader of the state BJP) and Praveen Togadia (the leader of the state VHP) regarding the “Christian threat” due to conversions of tribals. An emphasis on education The Sangh Parivar abroad put also a stronger emphasis on education than in India, although it is a clear priority there too. Many Hindus who settled down overseas are eager for their children to be more familiar with their religious tradition. The Western offshoots of the RSS have been keen to respond to their expectations. This constitutes one major and inevitable difference with the agenda of the Sangh Parivar in India. Youngsters, in this context, are even more a priority target than in India. Hence, the tenth item of the « Guidelines for vistaraks [full-time workers] » of the HSS recommends to those who start new shakhas to distribute the literature produced by the RSS primarily to students. Young Hindus in the diaspora settled in the West are often put on the defensive when they have to justify features of their religion which are causes for surprise or denigration, be they related to vegetarianism, the worship of the sacred cow, the different dress codes, the arranged marriages etc. The attractiveness of the Sangh Parivar partly comes from the organisation’s ability to offer ready-made answers to those who do not want to be apologetic about their culture. The VHP has been especially good at developing a true catechism to young Hindus. In the UK, it even published a textbook for the teachers in 1996: Explaining Hindu Dharma : A Guide for Teachers. The Sangh Parivar also supports sister initiatives of the same kind like the text book of Seeta Lakhani which gives a Hindu viewpoint against cloning, divorce, homosexuality and promotes Hindu nationalism. Moreover, the book warns the BBC against its anti-Hindu bias and publicises a map of India where the whole of Kashmir happens to be in India36. The youth is a traditional target of the Sangh Parivar, not only because they are easier to format, but also because they give a benign, even family-oriented image to the movement – through youth camps and Hindi courses37 - and because the RSS has always been an adept at attracting promising, brilliant teenagers. Students organisations play a major role in this game plan. In the US and in Canada, the Hindu Student Council is, in fact, more important than the 34 Sadhu Brahmaviharidas, Understanding Hinduism, Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpit, 2003. Brochure about the permanent exhibition of the Neasden temple : Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, London, Ahmedabad: Swaminarayan Aksharpit, 2004. 35 Ibid., p. 448. 36 Seeta Lakhani, Hinduism for Schools, Londres: Vivekananda Centre London, 2005, pp. 58, 105-6. 37 Parita Mukta, “The public face of Hindu nationalism”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 23, no. 3, May 2000. 10 HSS38. In the US, the VHP-A has tried hard to shape (or reshape) the history textbooks of California from 2005 onwards through sister organisations or affiliates like the Hindu Education Foundation, the Vedic Foundation and the Hindu University of America. This strategy, which shows how important access to the youth is for the Sangh Parivar, has generated a great deal of debates among American indologists.39 * The ethno-religious mobilization of the Hindu diaspora, when it takes place, is not only the product of some spontaneous allegiance to the homeland as Anderson’s theory of “long distance nationalism” suggested; it does not stem either from the combination of multiculturalism and racism of the Anglo-Saxon societies. It is largely the result of concerted actions on the part of very well structured organizations. The involvement of Hindus settled in Western countries in Indian politics and their plea in favour of a majoritarian culture owes much to the way in which the RSS and its affiliates have established themselves overseas and orchestrated a veritable process of "re-Hinduization." This assessment rehabilitates the role of political actors in a field where social forces are often construed as largely autonomous and spontaneous. In fact, one more actor, the State, should be brought in the picture too. Jaswant Singh, BJP minister in the Vajpayee government, considered that the Indians of the diaspora "now […] have to carry the message that India is preparing to be in the forefront as a global power to reckon with – not in the combative or confrontationist sense – but as a cultural and economic superpower."40 The State, from the late 1990s onwards, attempted to instrumentalize the diaspora. This evolution became particularly evident under the BJP governement. When it came to power in 1998, the networks that the Sangh Parivar had nurtured over the years finally had access to the highest executive echelons. The RSS supporters abroad could hope for a more business-friendly and pro-Hindu, pro-Western government in their country of origin. In turn, prominent leaders of the RSS like Atal Bihari Vajpayee and the then deputy Prime Minister, Lal Krishna Advani, could fully rely on their foreign contacts. The BJP, which is part of a global organization, had campaigned abroad and had received funds from foreign contributors (although this practice is officially illegal), was particularly attuned to the needs and demands of its supporters outside India. The fact that the BJP government appealed to the NRIs in order to counter the consequences of the US economic sanctions following the 1998 nuclear test and flagship measures like dual citizenship exemplify this. It was not only a matter of using the diaspora as a new group ambassador, but also to attract new investors. This is the spirit in which the now annual event of Pravasi Bharatiya Divas was initiated in 2003 with the slogan “The Global Indian Family Meets”. Although this event is a government initiative and is partially funded with public money, the first two Pravasi Bharatiya Divas- before the Congress came back to power in May 2004 - were far from being bi-partisan. On the contrary, the overwhelming presence of organizations belonging or affiliated to the Sangh Parivar and of publically pro-hindutva delegates indicated a clear collusion of the government and the RSS’s global network. So 38 See Campaign to Stop Funding Hate, Lying Religiously : The Hindu Students Council and the Politics of Deception (http://hsctruthout.stopfundinghate.org). 39 See the last chapter of C. Jaffrelot (ed.), Hindu nationalism. A reader, Princeton (NJ), Princeton University Press, 2007. 40 Jaswant Singh, “Conclusion,” Pioneers of prosperity: contributions of persons Indian origin , New Delhi, Antar-Rashtriya Sahayog Parishad. 11 finally, almost 60 years after the creation of the first shakha abroad, one could have said that “The Global Sangh Family Meets”. 12