Race and Revitalization in the Rust Belt: A Motor City Story

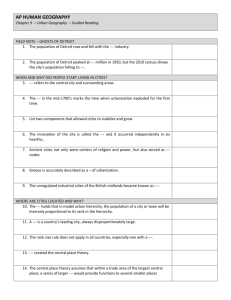

advertisement