COMMENTARY 600 603 LETTERS

advertisement

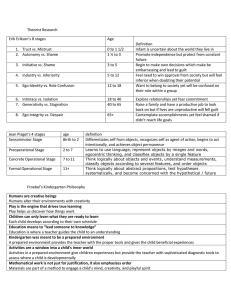

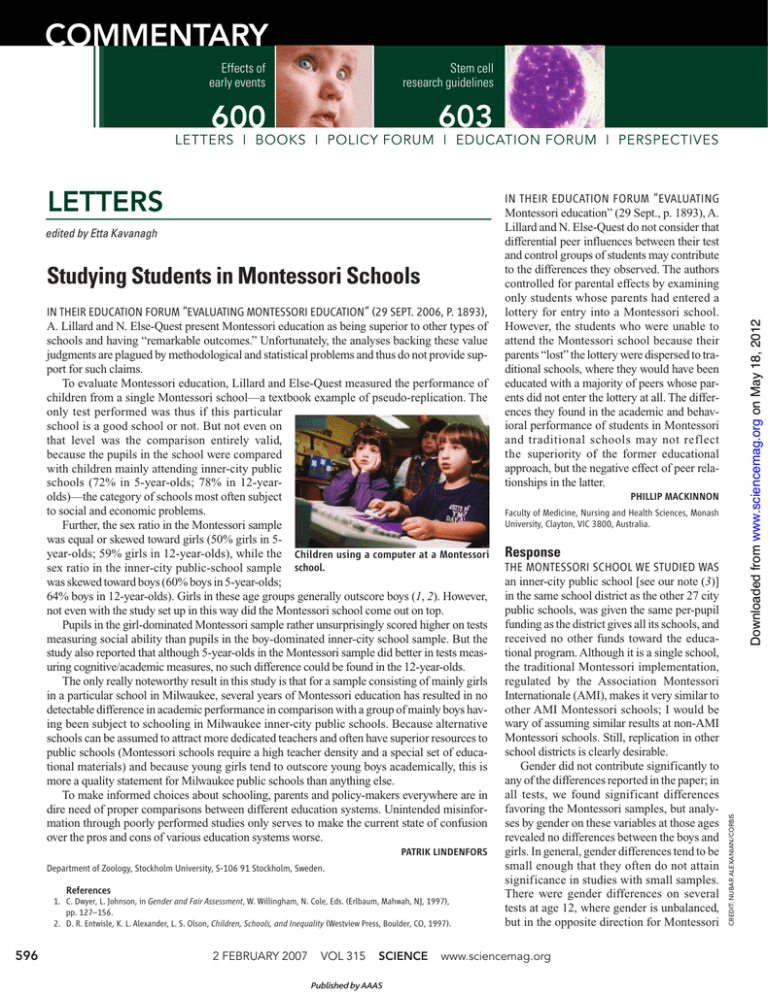

COMMENTARY Effects of early events Stem cell research guidelines 600 603 LETTERS I BOOKS I POLICY FORUM I EDUCATION FORUM I PERSPECTIVES Studying Students in Montessori Schools IN THEIR EDUCATION FORUM “EVALUATING MONTESSORI EDUCATION” (29 SEPT. 2006, P. 1893), A. Lillard and N. Else-Quest present Montessori education as being superior to other types of schools and having “remarkable outcomes.” Unfortunately, the analyses backing these value judgments are plagued by methodological and statistical problems and thus do not provide support for such claims. To evaluate Montessori education, Lillard and Else-Quest measured the performance of children from a single Montessori school—a textbook example of pseudo-replication. The only test performed was thus if this particular school is a good school or not. But not even on that level was the comparison entirely valid, because the pupils in the school were compared with children mainly attending inner-city public schools (72% in 5-year-olds; 78% in 12-yearolds)—the category of schools most often subject to social and economic problems. Further, the sex ratio in the Montessori sample was equal or skewed toward girls (50% girls in 5year-olds; 59% girls in 12-year-olds), while the Children using a computer at a Montessori sex ratio in the inner-city public-school sample school. was skewed toward boys (60% boys in 5-year-olds; 64% boys in 12-year-olds). Girls in these age groups generally outscore boys (1, 2). However, not even with the study set up in this way did the Montessori school come out on top. Pupils in the girl-dominated Montessori sample rather unsurprisingly scored higher on tests measuring social ability than pupils in the boy-dominated inner-city school sample. But the study also reported that although 5-year-olds in the Montessori sample did better in tests measuring cognitive/academic measures, no such difference could be found in the 12-year-olds. The only really noteworthy result in this study is that for a sample consisting of mainly girls in a particular school in Milwaukee, several years of Montessori education has resulted in no detectable difference in academic performance in comparison with a group of mainly boys having been subject to schooling in Milwaukee inner-city public schools. Because alternative schools can be assumed to attract more dedicated teachers and often have superior resources to public schools (Montessori schools require a high teacher density and a special set of educational materials) and because young girls tend to outscore young boys academically, this is more a quality statement for Milwaukee public schools than anything else. To make informed choices about schooling, parents and policy-makers everywhere are in dire need of proper comparisons between different education systems. Unintended misinformation through poorly performed studies only serves to make the current state of confusion over the pros and cons of various education systems worse. PATRIK LINDENFORS Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden. References 1. C. Dwyer, L. Johnson, in Gender and Fair Assessment, W. Willingham, N. Cole, Eds. (Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, 1997), pp. 127–156. 2. D. R. Entwisle, K. L. Alexander, L. S. Olson, Children, Schools, and Inequality (Westview Press, Boulder, CO, 1997). 596 2 FEBRUARY 2007 VOL 315 SCIENCE Published by AAAS Downloaded from www.sciencemag.org on May 18, 2012 edited by Etta Kavanagh IN THEIR EDUCATION FORUM “EVALUATING Montessori education” (29 Sept., p. 1893), A. Lillard and N. Else-Quest do not consider that differential peer influences between their test and control groups of students may contribute to the differences they observed. The authors controlled for parental effects by examining only students whose parents had entered a lottery for entry into a Montessori school. However, the students who were unable to attend the Montessori school because their parents “lost” the lottery were dispersed to traditional schools, where they would have been educated with a majority of peers whose parents did not enter the lottery at all. The differences they found in the academic and behavioral performance of students in Montessori and traditional schools may not reflect the superiority of the former educational approach, but the negative effect of peer relationships in the latter. PHILLIP MACKINNON Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3800, Australia. Response THE MONTESSORI SCHOOL WE STUDIED WAS an inner-city public school [see our note (3)] in the same school district as the other 27 city public schools, was given the same per-pupil funding as the district gives all its schools, and received no other funds toward the educational program. Although it is a single school, the traditional Montessori implementation, regulated by the Association Montessori Internationale (AMI), makes it very similar to other AMI Montessori schools; I would be wary of assuming similar results at non-AMI Montessori schools. Still, replication in other school districts is clearly desirable. Gender did not contribute significantly to any of the differences reported in the paper; in all tests, we found significant differences favoring the Montessori samples, but analyses by gender on these variables at those ages revealed no differences between the boys and girls. In general, gender differences tend to be small enough that they often do not attain significance in studies with small samples. There were gender differences on several tests at age 12, where gender is unbalanced, but in the opposite direction for Montessori www.sciencemag.org CREDIT: NUBAR ALEXANIAN/CORBIS LETTERS Asymmetry from symmetry 609 610 than the Letter presumes: Montessori boys at age 12 performed best of all the groups on those tests. In addition, the study was not set up to have gender representation differences across samples; the goal was equal representation, but the returned permission slips dictated the distributions. Although the 12-year-olds had 6 more years of Montessori schooling, and thus one could argue should have shown stronger academic differences than the 5-year-olds, they also had 6 more years of enculturation in their low-income communities and homes that might work against what happens inside the school walls. Although the current environment emphasizes only academic tests, social skills were included in this study, on the grounds that they are extremely important in life—often, one could argue, more important than having superior academic skills. Contrary to Lindenfors’s assumption, traditional Montessori actually has a rather low teacher density. The AMI standard teacher-child ratio is 1:28 to 1:35. Regardless, the notion that teacher-child ratio is related to student achievement is misguided: Relations have sometimes been found in first grade (1), but not consistently enough to claim it generally true (2). Also, Montessori is not more expensive than traditional schooling; once a classroom is outfitted with materials (at a cost of roughly $25,000), the costs per year are less (estimated at $800 per year by the North American Montessori Teachers’ Association) than in traditional classrooms because there are no textbooks to replace. The notion that perpupil expenditures have an impact on student achievement is also not upheld by the data (3). MacKinnon makes the excellent suggestion that child outcomes at the Montessori school might be the result of having peers whose parents entered them in a lottery. One way to investigate this is to see whether children in control schools that also admit by lottery (thus, their classmates might have listed that school as their first choice) did better than children at control schools that did not. Milwaukee does not make obvious to an outsider which schools admit by lottery, but they do indicate that Citywide Specialty Schools are more likely to. The control children in our study who were at Citywide Specialty Schools did not as a group perform as well as the children at the Montessori school studied, suggesting that the results were not simply due to schooling with peers whose parents entered them in a lottery. ANGELINE LILLARD1 AND NICOLE ELSE-QUEST2 1Department of Psychology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA. 2Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53202, USA. References 1. NICHD Early Childcare Research Network, Dev. Psychol. 40, 651 (2004). 2. R. G. Ehrenberg, D. J. Brewer, A. Gamoran, J. D. Willms, Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2, 1 (2001). 3. E. Hanuschek, Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 19, 141 (1997). Darwin: Not the First to Sketch a Tree IN THE PERSPECTIVE BY A. ROKAS, “GENOMICS and the tree of life” (29 Sept., p. 1897), the caption to the accompanying photo identifies Charles Darwin’s 1868 notebook sketch as “the first known sketch of an evolutionary tree.” This is mistaken. Nearly 60 years earlier, in 1809, Jean Baptiste Lamarck presented an evolutionary tree of the animals in Philosophie Zoologique (1). Modern evolutionary biologists would benefit from readTABLE SHOWING THE ORIGIN OF THE VARIOUS ANIMALS. Worms. Infusorians. Polyps. Radiarians. Insects. Arachnids. Crustaceans. Annelids. Cirrhipedes. Molluscs. Fishes. Reptiles. Birds. Monotremes. Amphibian Mammals. Cetacean Mammals. Ungulate Mammals. Unguiculate Mammals. Lamarck’s evolutionary tree [redrawn from (1)] www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE Published by AAAS VOL 315 ing Lamarck; there is much nonsense in his work, but there are also quite substantial insights. Lamarck towered over his contemporaries in both the rigor of his evolutionary thought and the identification of a credible, coherent, and falsifiable hypothesis for the mechanism of evolutionary change. That his mechanism was wrong does not take anything away from the originality of his thought (although his failure to test his hypothesis is not consistent with current scientific practice and is largely responsible for his current neglect). MARK WHEELIS Section of Microbiology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA. E-mail: mlwheelis@ucdavis.edu Reference 1. J. B. Lamarck, Zoological Philosophy: An Exposition with Regard to the Natural History of Animals, H. Elliot, transl. (Macmillan, London, 1914), p. 179 [reprinted by the University of Chicago Press, 1984]. Downloaded from www.sciencemag.org on May 18, 2012 X-ray diffraction of bismuth Human Dispersal into Australasia WE AGREE WITH P. MELLARS THAT LONGdistance dispersal of prehistoric human populations may involve multiple small founder effects with consequent loss of genetic diversity—and possibly also cultural traits—with increasing distance from source (“Going east: new genetic and archaeological perspectives on the modern human colonization of Eurasia,” Special Section: Migration and Dispersal, Review, 11 Aug. 2006, p. 796). However, Australian genetic and stone artifact data are not consistent with this pattern. Genetic studies of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of indigenous Australians have only just begun, with fewer than 300 individuals sampled from less than 5% of the continent’s landmass (1–3). Even so, observed mtDNA variation in Australians already includes five Australia-specific haplogroups, and more if New Guinea samples are added to represent the landmass that was Sahul for most of the 50,000 to 60,000 years that humans have occupied the island continent (4, 5). Larger, continent-wide samples may well show Australia to have been as genetically diverse as Europe or Africa. The earliest Australian stone artifact industries consist of small flakes and flake tools with some prepared platform cores and occasional radial or centripetal cores, and are strongly influenced by the form of local stone materials (6, 7). It is unlikely that these industries carry the sort of cultural information that Mellars and others assume. His argument that these are “Mode 4” (Upper Palaeolithic) industries that devolved in response to local conditions (8) lacks parsimony, given that 2 FEBRUARY 2007 597 LETTERS MIKE A. SMITH,1 PAUL S. C. TACON,2 DARREN CURNOE,3 ALAN THORNE4 1National Museum of Australia, GPO Box 1901, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia. 2School of Arts, Griffith University, PMB 50, Gold Coast Mail Centre, QLD 9726, Australia. 3School of Medical Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia. 4Archaeology and Natural History, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia. References 1. K. Huoponen, T. G. Schurr, Y.-S. Chen, D. C. Wallace, Hum. Immunol. 62, 954 (2001). 2. S. M. van Holst Pellekaan, M. Ingman, J, RobertsThomson, R. M. Harding, Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 131, 282 (2006). 3. J. C. Presser, A. J. Deverell, A. Redd, M. Stoneking, Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasmania 136, 35 (2002). 4. J. Friedlaender et al., Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1506 (2005). 5. M. J. Pierson et al., Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1966 (2006). 6. R. G. Roberts, R. Jones, M. A. Smith, Nature 345, 153 (1990). 7. W. Shawcross, Archaeol. Oceania 33, 183 (1998). 8. R. Foley, M. M. Lahr, Camb. Archaeol. J. 7, 3 (1997). 9. A. Brumm et al., Nature 441, 624 (2006). 10. P. J. Brantingham, A. I. Krivoshapkin, L. Jinzeng, Y. Tserendagva, Curr. Anthropol. 42, 735 (2001). 11. M. Otte, A Derevianko, Antiquity 75, 44 (2001). 12. X. Gao, C. J. Norton, Antiquity 76, 397 (2002). Response I APPRECIATE SMITH ET AL.’S SUPPORT FOR my general model of a progressive loss in the genetic and technological diversity as modern human populations dispersed from their African homeland to other parts of the world. However, I find the remainder of their arguments unconvincing. Despite the high genetic diversity of modern Australian and New Guinea populations, the current genetic data indicate unambiguously that all of these populations derive ultimately from the two out-of-Africa mtDNA lineages M and N (in turn derived directly from the African L3 lineage) and from the Y chromosome founder lineages C and F (1–5). Any subsequent diversity in these populations must derive from genetic mutations that occurred after the original out-of-Africa dispersal around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago [(1, 2, 4, 5); my Report]. I am equally unconvinced by their observations on the archaeological data. My own 598 CORRECTIONS AND CLARIFICATIONS Reports: “Dual infection with HIV and malaria fuels the spread of both diseases in sub-Saharan Africa” by L. J. Abu-Raddad et al. (8 Dec. 2006, p. 1603). The first sentence of the paper, “In Africa, an estimated 40 million people are infected with HIV, resulting in an annual mortality of over 3 million (1), while over 500 million clinical Plasmodium falciparum infections occur every year with more than a million malaria-associated deaths…” is incorrect. These numbers refer to worldwide numbers for both infections, not just in Africa. The number of HIV-infected persons in Africa is approximately 25 million, and the number of malaria infections is roughly 350 million. Perspectives: “How fast does gold trickle out of volcanoes?” by C. A. Heinrich (13 Oct. 2006, p. 263). In line 7 of the first full paragraph of column 3, “10 to 20 mg” should be “10 to 20 µg.” TECHNICAL COMMENT ABSTRACTS COMMENT ON “Rapid Advance of Spring Arrival Dates in Long-Distance Migratory Birds” Christiaan Both Jonzén et al. (Reports, 30 June 2006, p. 1959) proposed that the rapid advance of spring migration dates of longdistance migrants throughout Europe reflects an evolutionary response to climate change. However, most migrants should not advance their migration time because the phenology of their breeding grounds has not changed. It is more likely that migration speed has changed in response to improved environmental circumstances. Full text at www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/315/5812/598b RESPONSE TO COMMENT ON “Rapid Advance of Spring Arrival Dates in LongDistance Migratory Birds” Niclas Jonzén, Andreas Lindén, Torbjørn Ergon, Endre Knudsen, Jon Olav Vik, Diego Rubolini, Dario Piacentini, Christian Brinch, Fernando Spina, Lennart Karlsson, Martin Stervander, Arne Andersson, Jonas Waldenström, Aleksi Lehikoinen, Erik Edvardsen, Rune Solvang, Nils Chr. Stenseth Both’s comment questions our suggestion that the advanced spring arrival time of long-distance migratory birds in Scandinavia and the Mediterranean may reflect a climate-driven evolutionary change. We present additional arguments to support our hypothesis but underscore the importance of additional studies involving direct tests of evolutionary change. Full text at www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/315/5812/598c impression is that the earliest Australian technologies are far too simple, generalized, and “expedient” (as they seem to accept) to support any specific technological links with other technologically simple and expedient technologies, such as those from Flores and other earlier Pleistocene sites in southeast Asia (my Report). I am not aware of any convincing Levallois or other “Mode 3” (Middle Palaeolithic) technologies in Australia and see no reason why the Australian technologies should not be viewed as heavily simplified or “devolved” forms of Upper Palaeolithic (“Mode 4”) technologies, under PAUL MELLARS Letters to the Editor Letters (~300 words) discuss material published in Science in the previous 6 months or issues of general interest. They can be submitted through the Web (www.submit2science.org) or by regular mail (1200 New York Ave., NW, Washington, DC 20005, USA). Letters are not acknowledged upon receipt, nor are authors generally consulted before publication. Whether published in full or in part, letters are subject to editing for clarity and space. 2 FEBRUARY 2007 VOL 315 SCIENCE Published by AAAS the influence of varying raw material effects and other purely local economic adaptations (my Report). I note that they make no reference to the apparent similarities between the forms of the early Australian “horse-hoof ” cores and simple forms of single-platform blade cores (my Report). And I am totally unconvinced by the arguments for purely local origins of Upper Palaeolithic/Mode 4 technologies in northeast and Central Asia [my Report; (6)]. To employ these data to support some form of multiregional, as opposed to African, origins for modern Australian populations would seem to be poorly founded in either the genetic or archaeological data. Department of Archaeology, Cambridge University, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, UK. References 1. P. Forster, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 359, 255 (2004). 2. P. Forster, personal communication. 3. T. Kivisild et al., Genetics 172, 373 (2006). 4. P. Mellars, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9381 (2006). 5. M. Richards, H.-J. Bandelt, T. Kivisild, S. Oppenheimer, Nucleic Acids Mol. Biol. 18, 223 (2006). 6. P. Mellars, Evol. Anthropol. 15, 167 (2006). www.sciencemag.org Downloaded from www.sciencemag.org on May 18, 2012 similar assemblages are found in middle Pleistocene and other early contexts in neighboring parts of Southeast Asia (9). Also, the balance of evidence indicates only a weak relationship between Mode 4 industries and the spread of modern humans (8). In northeast and central Asia, these industries appear to have locally developed (10) and subsequently diffused into Europe and the Near East, rather than originating in Africa (11, 12). Collectively, these data suggest that the cultural and genetic history of Australasia is more complex than a single dispersal model such as “Out-of-Africa 2” allows.