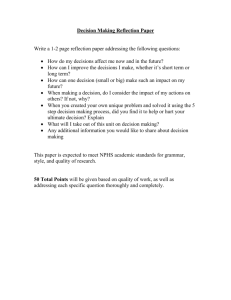

Addressing stAndArd Establishing the

advertisement