o f Highest Court in the Land

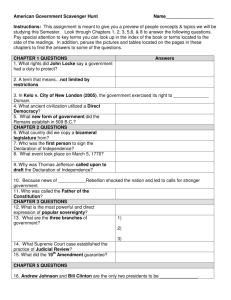

advertisement