NICOR NATIONAL ADULT CARDIAC SURGERY AUDIT:

advertisement

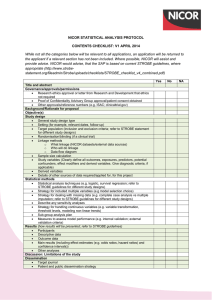

NICOR NATIONAL ADULT CARDIAC SURGERY AUDIT: RESPONSE TO PROFESSOR NICK BLACK’S REPORT INTO THE REVIEW OF DATA VALIDATION AND STATISTICAL PROCESSES FOR CONSULTANT OUTCOMES PUBLICATION 2014 (2010-2013 DATA) November 19th 2014. NICOR Executive Professor John Deanfield Dr Mark de Belder Dr Peter Ludman Professor Adam Timmis Professor Ben Bridgewater Professor Adam Timmis Dr Julie Sanders NICOR REPONSE TO NICK BLACK REPORT Professor Nick Black was asked to review the National Adult Cardiac Surgery Audit (NACSA) to provide assurance that the NACSA data were fit for purpose for publication for NHS England’s consultant outcomes publication programme (COP). NICOR would like to thank Nick Black and his panel for their report (Appendix I). They have acknowledged the complexity of this process, made recommendations for potential improvements, and highlighted the chain of responsibility. They have concluded that, in spite of these complexities, the data are of sufficient completeness and accuracy to allow for a comparison of individual consultants. They have recommended further development of the processes involved and the risk adjustment model, but have concluded that the adopted method is fit-for-purpose. The panel has raised some important points. NICOR would wish to highlight a number of issues related to his report. 1. NACSA management: The NACSA is managed by the National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) – there is extensive governance surrounding this programme, within NICOR, between NICOR and the professional society (the SCTS), and between NICOR and HQIP. In particular the project group managing the audit has been appropriately configured with patient, lay, methodological, project management and professional representation. All minutes are made publically available. There is limited specific national guidance on consultant data validation, data sign-off, risk adjustment or definition of outliers. All guidance that does exist has been complied with by NICOR. In the absence of specific guidance, NICOR has developed methodologies which Nick Black and colleagues have acknowledged to be fit for purpose, but the report raises issues about a number of aspects of the methodologies applied. NICOR would like to point out that all methodologies used were developed with appropriate governance with independent statistical review. All methodologies used for both risk adjustment and definition of outliers was published openly through peer review, (Eur J Cardiothorac Surg (2014) 45 (2): 225233.doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt476). NICOR believes that is has been open and transparent about all these aspects of its work. 2. Case ascertainment: As described in the NICOR report submitted to Nick Black, there is no gold standard for case ascertainment for adult cardiac surgery. Following a review between NICOR and the National Advisory Group on Clinical Audit and Enquiries (NCAGCAE) last year it was agreed to work toward innovative ways of combining the datasets to achieve optimal information on case ascertainment. NICOR is working towards this, but these data are not yet available for the current round of COP. 3. Data collection: The definitions for the NACSA dataset and the EuroSCORE variable are freely available, and have been disseminated to units. Recent events have highlighted inconsistencies in the way these data definitions have been applied locally. NICOR would add that even widely accepted international benchmarking algorithms such as the EuroSCORE or EuroSCORE II have not been developed with issues of scientific rigour such as examinations of test-retest reliability or inter-observed variability for the risk factors used in the models, nor have these algorithms been accompanied by detailed user manuals, but NICOR accept that the COP programme is making these issues increasingly important and will respond by reviewing the dataset in detail, and issuing appropriate guidance to surgeons and units. 4. Data completeness: NICOR recognises that that the process of imputation used for missing data is only one of a number of available options, but the process chosen has been selected for specific reasons that have been openly disseminated and described in detail in the peer review publications. NICOR is familiar with other techniques and will review the options for subsequent rounds of COP. 5. Data validation: The audit structures within participating hospitals should ensure that the data sent to NICOR are as complete as possible. NICOR believes that its process for data validation for the NACSA with the units (which in the case of this round of COP have involved four repeated rounds communicating with the units and positive sign-off prior to publication) have been particularly extensive compared to other national audits. Data quality must always ultimately be a local responsibility, but audit providers must support that responsibility. NICOR and SCTS have taken significant steps to flag up to surgeons and units the shared responsibility required for data to be fit for purpose, as described in the report submitted to Nick Black. 6. Feedback to audit staff: In response to one specific issue raised by Prof Black, NICOR would add that audit staff are notified and sent the units’ data, as well as communicating with the clinical staff at each hospital. As Prof Black describes one particular item (unstable angina) was considered as part of the revalidation process, but all data items were included in the feedback to units, highlighting all fields that had an unexpected variation from the national average, both at hospital and individual surgeon level. Finally NICOR notes Prof Black’s comments with respect to the funnel plot methodology used but would note that these would act to be more, rather than less, sensitive in detecting unexpected variation for potentially high incidences. Given that concerns had been raised about erroneously high incidences leading to false negative issues on a surgeon outlier analysis, the issue about the lower funnel limit is less significant. NICOR will continue to review the methodologies used in this process. 7. Risk adjustment and outlier detection methodology: NICOR has taken these aspects particularly seriously and has published a series of peer review manuscripts on the methodology used, the reasons for their selection, and potential limitations. In particular NICOR believes that the approach to recalibration to use contemporary coefficients to give true peer group benchmarking, recalibrated for each year of scrutiny, is particularly robust and acts in the best interests of patients in an environment of on-going quality improvement. NICOR believes it has been particularly transparent about these aspects of its processes. There are limitations of all methods but NICOR will continue to refine its processes. NICOR welcomes any national guidance on these issues and would be happy to contribute to developing this alongside other stakeholders. APPENDIX I: Report of an independent review Full report Comparison of consultants' outcomes in adult cardiac surgery Report of an independent Review Group (Chair: Nick Black) Background In April 2014, NICOR together with the Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons provided consultant outcome data based on April 2010-March 2013 to their members. This included profiles of the risk factor incidences for each consultant. Concern was expressed about one surgeon having reported rather extreme values for some risk factors, which would have markedly increased his expected mortality (and thus under-estimated his risk adjusted mortality).Enquiries followed and disciplinary action was taken by relevant authorities. This raised the concerns of other surgeons who challenged the validity of the data more generally. In particular there were concerns, shared by NICOR and SCTS, about the validity of one risk factor, unstable angina. In June-August NICOR asked all consultants to repeat the validation of their own data and confirm it's authenticity. On 6 October 2014, Professor Sir Bruce Keogh requested that the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership provide assurance that consultant level outcome data were fit to publish, particularly regarding the adequacy of data validation and analysis. In order to do that he requested HQIP secure an independent assessment. Review method On 8 October, as Chair of the National Advisory Group for Clinical Audit & Enquiries, Nick Black agreed to undertake a rapid review and advise HQIP. Three other members of NAGCAE or NAGCAE Sub-Groups with methodological expertise were recruited (Professor Jan van der Meulen; Professor Kathy Rowan; Dr Robert Grant) plus Dr David Harrison (ICNARC), to assist in addressing three questions: 1. Are the data management and validation processes that are used to produce the adult cardiac surgery database fit-for purpose (ie comparing consultants' outcomes)? 2. Are the data of sufficient completeness and validity for comparing consultants? 3. Is the method of risk adjustment fit-for-purpose? On 10 October NICOR provided a detailed account of the processes they had used to collect, validate and analyse data from all cardiothoracic consultants in England, Wales and Scotland. After reviewing it, further clarification and additional information was requested from NICOR on 13 October. This was received on 14 October (see below). Findings 1. Are the data management and validation processes that are used to produce the adult cardiac surgery database fit-for purpose (ie comparing consultants' outcomes)? 1.1 Case ascertainment Case ascertainment (recruitment proportion) is determined by comparison with the number of cases recorded in the hospital administrative database (Hospital Episode Statistics in England). NICOR defend this approach by referring to work that was carried out by the Clinical Effectiveness Unit of the Royal College of Surgeons that showed the overall number of patients included in the audit between April 2007 and March 2009 (37712) was similar to the corresponding number in HES (37542). However, that report also found differences in some units (ranging from 37% fewer to 22% more patients in HES than in the audit). The differences in 30-day mortality within units were even larger (ranging from 34% fewer to 59% more deaths in HES than in the audit). The report also indicated that it is likely that for a small number of consultants in two trusts the number of procedures according to HES were considerably different from the number according to audit data. It's not clear why such discrepancies arise and which database is the more accurate. An analysis of linked data would be able to provide not only an estimate of case ascertainment but also a better understanding of the differences, assuming they have persisted into the 2010-13 data. It might also be worth comparing ascertainment with an alternative data source such as operating theatre information systems. 1.2 Data collection There is limited knowledge of how data collection rules and definitions are actually applied locally. It is unclear what standard instructions exist regarding data collection, such as a manual with rules and definitions for each variable, how these are communicated to those responsible for data entry locally, and how individuals are trained. For example, for the ten items of data used to derive 'critical preoperative state' (one of the variables required for the EuroSCORE), it is important to know about several aspects of the data collected such as what definitions are used, how objective they are, what algorithms are used for derivation, what is the validity of the raw rather than the derived data etc. It is also concerning that invalid data are logically mapped to sensible data on processing. National clinical audits can be made less likely to be manipulated by individual consultants. For example, the staging data in the cancer audits comes from the pathology laboratories and other data items are determined by multidisciplinary teams. This makes audits, such as this one, that rely on data entered by consultants, more vulnerable to data manipulation. 1.3 Data completeness There were very few patient records that lacked data on outcome (dead/alive) partly because those with missing data are completed and validated through a comparison with ONS mortality records. If after this process the survival of a patient is still unclear, it is assumed that a patient has died, providing a strong disincentive for consultants to fail to provide this information. Similarly, missing data for variables needed for risk adjustment are imputed with the values that give the least possible increasing predicted risk. This approach is taken to encourage consultants to record all data items because not reporting data items would lead to worse outcomes being reported. However, imputing missing data for variables included in the risk adjustment model with values that give the least possible increase in risk may have a detrimental impact on the ability to develop the risk adjustment model. More advanced imputation techniques are available that reduce bias and increase precision and should be considered. 1.4 Data validity Three principal mechanisms are in place to check data validity. First, consultants are required to authenticate their own data. This approach clearly places the responsibility for validity on the consultants rather than being assumed by NICOR. This makes it difficult for NICOR to be confident that consultants are not wilfully misleading the system. Reassurance about the data validity might be increased if hospital managers or audit staff were involved. It is unclear what action is actually taken by consultants when asked to validate their own data (eg re-enter a random sample, review specific variables for which they are outliers etc). Second, NICOR carry out a number of range checks for data values and tests for internal consistency between variables. Third, the data items used for risk adjustment are assessed by comparing their incidence for each consultant. This allows for consultants with significantly different rates to be identified. While this cannot distinguish justifiable 'outliers' (ie consultants with a specialist case-mix) from those who may be supplying erroneous data (gaming), further qualitative local enquiry can determine which is the case. There are three concerns about the current approach to validation. First, if data on risk factor incidence for validating is provided to consultants alongside their risk-adjusted results there is a danger of the latter influencing the former. The two activities should be divorced from each other with the validity of the risk factor data checked first. Second, the repeat validation carried out during summer 2014 appears to have asked consultants to focus on one specific variable (unstable angina) so as to minimise the burden for consultants. Given the recent history of serious concern about this audit, a more wide-ranging and thorough revalidation might have been appropriate to help restore confidence. The third, more minor point, is that the use of funnel plots based on the Normal distribution for binary risk factor data is somewhat questionable. Certainly the lower funnel lines (which are admittedly of less interest) will be completely irrelevant as they frequently correspond to a prevalence of zero. The upper funnels from the Normal approximation will have somewhat less dispersion than an exact binomial approach, particularly at small sample sizes. 2. Are the data of sufficient completeness and validity for comparing consultants? Overall, despite some concerns about the processes employed to collect and validate data, it appears the data are of sufficient completeness and accuracy to compare consultants. In addition, each and every consultant has authenticated their data. Further improvements to the process could be made. The identification of consultants with an outlying incidence of a risk factor has been based on fairly crude analysis of funnel plots. While the Winsorization of these funnel plots may do a reasonable job of accounting for overdispersion in risk factors that are continuously (but not evenly/randomly) distributed across providers, it will be much worse at dealing with sub-populations of providers (particularly of individual consultants) that do or don't routinely deal with certain types of patients. In such cases, we may expect the individual data points to form two (or more) sub-funnels. There is possibly some suggestion of this for 'Emergency or Salvage', 'Other than isolated CABG' and 'Surgery on Thoracic Aorta'. If it were possible to categorise the surgeons in some way by sub-specialties or the types of operations they perform then examining separate funnels for these categories may be more informative. Concern about deliberate attempts to obscure poor outcomes by gaming the risk factor data remain (ie consultants whose results are not flagged up as outliers). If data manipulation takes place, it is most likely that it would concern data items that are included in the risk adjustment model because manipulating the outcome (mortality), would be much more likely to be detected. One way to explore to what extent any issues in data on risk factors may mask poor performance is to compare observed and adjusted outcomes. Large differences would suggest unusual risk factor profiles. 3. Is the method of risk adjustment fit-for-purpose? The risk adjustment used by NICOR is based on a logistic model of hospital mortality that discriminates well between patients who die and those who survive and produces mortality predictions that fit observed mortality well. While further refinement may not lead to large improvements in the risk adjustment method, the choice of a recalibrated EuroSCORE deserves further consideration. Four options have been considered by NICOR: Logistic EuroSCORE (as published) Refitted logistic EuroSCORE Refitted modified EuroSCORE Recalibrated EuroSCORE Using logistic EuroSCORE as published is quickly (and appropriately) rejected as it is clearly poorly calibrated. However, the approach by which they have selected a cubic transformation of the logistic EuroSCORE (the recalibrated EuroSCORE) over either refitted model is unclear. The basis for the selection appears to be that the recalibrated EuroSCORE more closely follows a straight line of observed to predicted risk than the refitted approaches. However, this is, in a sense, a self-fulfilling prophecy - the method applied is solely designed to produce such a straight line, without any consideration of what it actually means in terms of the underlying risk factors. The thing that statistically we would be most concerned about in applying an out-of-date model, such as EuroSCORE, is 'differential miscalibration'. In other words, that the effect of some risk factors on outcome has changed (relative to the original development population) differently from other risk factors. The fact that a simple linear transformation of the logistic EuroSCORE did not produce good calibration and a cubic transformation was required strongly suggests that such differential miscalibration is present. The cubic transformation masks this (by giving good overall calibration according to predicted risk) but does not address it directly - only refitting the model can do this. Essentially, any two patients that received similar predicted risk to each other under the original logistic EuroSCORE will still receive similar predicted risk to each other under the recalibrated EuroSCORE and this assumption (inherent in this approach to recalibration) appears unlikely to hold true. Therefore, while there would be some concern about the amount of miscalibration exhibited by the refitted models, either of these is likely to give a fairer comparison of consultants than the recalibrated EuroSCORE. This limitation is very briefly acknowledged: "A disadvantage is that this approach does not account for the varying contemporaneous adjustments each risk factor might have." The only way to provide any reassurance regarding this would be to look at the calibration within subgroups defined by risk factors rather than solely by overall predicted risk. For example, does the recalibrated model perform equally well across different age groups, sexes, those with and without chronic pulmonary disease, etc? It is not clear whether this has been done Recommendations It is clear that the processes for data collection and validation need to be improved, as do the governance arrangements that oversee these and other processes. Case ascertainment needs to be investigated more rigorously and both data completeness and data validity could be further improved. The method of data collection allows for variation on how consultants interpret and define some key risk factors, a situation that needs attention. Despite our concerns about these aspects of the current processes, the data appear to be of sufficient completeness and validity to be used to compare consultants. It is reassuring that the clinical lead in all units have confirmed their satisfaction with the accuracy of the data their consultants colleagues have provided and had the opportunity to validate a second time. This minimises the risk that any consultant found to be a poor outlier (more than 3 standard deviations worse than expected) has any justification to claim an unjustifiable judgement. While we would recommend further investigation and development of the risk adjustment model, the adopted method is felt to be fit-for-purpose. The principal risk is that a consultant with poor outcomes will not be detected as the current data collection and validation processes can allow a misleading assessment of the consultant's outcome. Improvements to the governance and data management processes are required to reduce this risk in future years.