[THIS SPACE MUSTBE KEPT BLA Understanding and Applying Trigger

advertisement

Shikakeology: Designing Triggers for Behavior Change: Papers from the 2013 AAAI Spring Symposium

[THIS SPACE MUSTBE KEPT BLA

Understanding and Applying Trigger

Piggybacking for Persuasive Technologies

Ashutosh Priyadarshy, Duylam Nguyen-Ngo

EEMe labs

{ashutosh, duylam}@eemelabs.com

Abstract

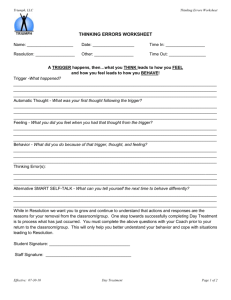

An archetypal Shikake is the use of the shrine symbol, in

Japan, to prevent people from public urination, spitting,

and other crude acts. The principle is simple. Shrines symbolize holiness; upon seeing this symbol people are compelled to behaviors congruent with their ideas of holiness.

For many, public urination and spitting are obviously excluded from any set of holy behaviors. Figure 1 shows an

example of such a shrine symbol. The low design expertise

required in creating this persuasive “technology” is apparent as the symbol can be painted anywhere a designer desires. Being placed in a public place, it readily triggers anyone who understands the cultural significance of a shrine;

this is a very low barrier to trigger comprehension. The

trigger achieves long-term behavior change in two ways.

First, by always being present in the same location it

triggers behaviors congruent with holiness every time a

person sees it. Second, the trigger only reminds viewers of

the concept of holiness. By piggybacking on a cultural or

social value, the trigger augments the viewer’s motivation

to be holy. This increase in motivation drives the viewer

past the behavior activation threshold. Unlike other triggers, like those in the Fogg Behavior Model, that are designed to compensate for a lack in either motivation or

ability the shrine trigger acts by pushing motivation levels

up thus causing intrinsically-motivated behaviors (Fogg

2009). Examples of Shikake are abundant and diverse. Another classic example is the placement of curious objects in

public places that draw the attention of people and bring

them closer to reading a sign or performing some action

(Matsumura 2007).

Even simpler is the example of a piece of tape on the

spine of a book that spans diagonally across a row of books

on a bookshelf. When placing books on the shelf people

simply complete the “puzzle” of tape and avoid dealing

with the alphabetization of the books. Such Shikake are effective but starkly different from the shrine example.

This paper presents a new methodology for designing motivation-augmenting products along with two example cases.

Like the tiny habits methodology, trigger piggybacking

builds upon the Fogg Behavior Model but unlike the tiny

habits methodology it incorporates a Shikakelogical approach to behavior change. Trigger piggybacking claims

that a trigger rooted in a value system will produce longterm continuous behavior change. By embodying a relevant

value system, the trigger reinforces values and leaves itself

open to interpretation. This openness is the key to driving a

user’s desire to perform a behavior. Trigger piggybacking

adds to the toolkit of those that design persuasive technologies.

Background and Motivation for

Trigger Piggybacking

Shikake is the Japanese term for a specific class of behavior triggers. A trigger deemed to be a Shikake combines

the following features: low design expertise, wide range of

target users, long term continuous behavior changes, and

spontaneous behavior activation. Several archetypal Shikake are timeless, physical manifestations capable of activating desired behaviors simply by being seen. These analog

archetypes inspire new Shikakeological perspectives on

captology and captology design methodologies. In applying Shikakeological principles to captology, we introduce

the concept of Trigger Piggybacking. A particularly potent

Shikake apt for transition into digital form. In understanding Trigger Piggybacking we provide background and historical examples of archetypal Shikake, definitions and advantages of Trigger Piggybacking, examples of current

technologies that use Trigger Piggybacking, design

tradeoffs in comparison to other persuasive design techniques, and finally a methodology for using Trigger Piggybacking.

Copyright © 2013, Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

79

observer the freedom and autonomy to act as they wish;

freedom and autonomy in choosing behaviors are cornerstones of Shikake.

The interpretation of a value system ties the first and second effect together; it is possible that the trigger carries no

meaning for the observer or that he acts upon that trigger in

a way that is dissimilar to the designer’s interpretation.

Tradeoffs are inherent in any design. In the case of trigger

piggybacking the transaction is between a single deliberate,

desirable action and the potential for a multiplicity of selfmotivated, desirable actions. Associating a trigger with a

value system and in the case of digital mediums causes the

observer to interact with the digital medium as if the rules,

norms, and values of the real world apply in the digital

one. An alternative interpretation is that trigger piggybacking compels observers to express their motivations and

values via behaviors that would be otherwise suppressed

for any number of reasons. The shrine gate example is a

clear illustration of an analog trigger piggyback. Before

proceeding to a design methodology we illustrate an example of Digital Trigger Piggybacking.

Figure 1: Shrine Gate trigger to prevent vandalism

The shrine Shikake has potential to be more persuasive

due to two key differences. First, subjects are left to their

own interpretation of the symbol and its meaning and social implications. Second, the Shikake does not pigeonhole

the subject into a single action or behavior but into a set of

behaviors that are congruent with the individual’s interpretation of the trigger. Such triggers can effectively translocate value systems from real-world into the digital realm

because subjects create and associate values, social and

cultural norms with the sight of the trigger. Finally, evidence in captology and social psychology that humans perceive computers as social entities indicates promise in designing triggers that migrate values and norms from real

world to digital world (Fogg 2002, Fogg et al. 2009, Nass

et al. 1994, Takeuchi et al. 2000). In particular, studies in

reciprocity relationships show that human actors are more

likely to be persuaded by computer actors that share something in common with them (Takeuchi et al.)

From this motivating example we can define Trigger

Piggybacking. Trigger Piggybacking is a persuasive design

technique and methodology in which a highly observable

trigger is designed and placed to remind an observer of a

particular set of values or norms that tend to alter the observer’s behavior. In particular, we focus on Trigger Piggybacking that, in a digital medium, reminds an observer

of values that exist in their ‘analog’ existence. The central

difference in a piggybacked trigger and a traditional trigger, such as those expounded in the Fogg Behavior Model,

is that instead of “[associating] the trigger with the target

behavior” the trigger is associated with a target value system (Fogg 2009). Association with a target value system

results in the following effects: persuading various behaviors, less predictability in passing activity threshold, and a

blending of media and self managed behavior change. Discussion of the shrine symbol illustrates the effect of various behaviors. The trigger represents a concept leaving the

Analysis and Application

To facilitate the addition of the trigger piggybacking technique into a designer’s toolbox we detail example usages,

tradeoffs, a three-step design process and an educational

example.

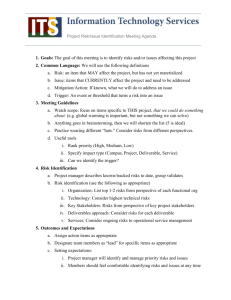

Fitbit: Translating Values from Analog to Digital

The Fitbit is a wireless activity tracker worn unobtrusively

throughout the day. It monitors several fitness metrics like

steps taken, distance walked, caloric output, and sleep cycles. The Fitbit is packed with bleeding edge technology to

capture, monitor and interpret fitness and health data. The

key user experience element is a digital flower that correlates with a user’s fitness level shown below in Figure 2.

High activity levels cause the flower to grow whereas low

activity levels cause it to shrink. The digital flower’s simplicity is a classic Shikake. The growth of the flower is a

powerful trigger that creates an association with well-being

and health. Due to this association the Fitbit flower is able

to unlock the potential of persuading multiple behaviors instead of a single behavior. As explained above this trigger

also does not result in the predictability of an alarm clock

or other timed trigger. The designer cannot predict how

much and with what intensity a user will perform behaviors that improve their well-being (and flower’s wellbeing). Finally, users tend towards a blend of media and

self managed behavior change because the flower does not

explicitly demand an intentional action.

80

spontaneity and creativity on behalf of the user. In trigger

piggybacking there is no guarantee of when and how a user

will act. The scope of behaviors varies between the two

methodologies. Tiny habits focuses on accomplishing a

single habit that develops into a single behavior. By nature

of Shikake, trigger piggybacking allows for the interpretation of the trigger thus a set of behaviors is realizable, not

just a single action or behavior. For example, someone

who follows Tiny Habits might start flossing everyday but

someone who experiences a well-designed piggybacked

trigger would feel compelled to brush, floss, rinse, avoid

candy or any other behavior that falls within the scope of

the value of dental hygiene.

The characteristics of the methodologies affect the behavior adoption time. By focusing on small, low hanging

accomplishments, tiny habit users easily begin practicing

the behavior and over time, the tiny habit grows and becomes fully developed. There is a vertical path to achieving and adopting the behavior making design issues apparent, quickly. Thus, behavior adoption time is shortened

greatly. Trigger piggybacking focuses more on values and

organically amplifying latent behaviors and motivations;

different perspectives then generate different interpretations. The openness means variance in trigger interpretation, which leads the user to choose within a set of behaviors. With the freedom, users have the ability to reassess an

interpretation and re-frame the presented trigger and follow

the path to a new set of behaviors. Since Trigger Piggybacking is value based and not timing based a designer

cannot predict the adoption time of a behavior. The designer uses the constant interaction with the trigger as a way of

augmenting the user’s desire to perform behaviors that express latent motivations. This is conducive for long-term

continuous behavior change. There is not a right or wrong

methodology; the optimal methodology is defined by the

designer’s goals. If there is a clear short-to-medium term

single behavior, then tiny habits could be the best fit. If

long-term continuous behavior change is the goal, then

trigger piggybacking could be the best fit.

Figure 2: Fitbit device

Comparison of Existing

Frameworks & Methodologies

Several frameworks and design methodologies exist for

creating persuasive technologies. To illustrate the advantages and disadvantages of the Trigger Piggybacking

concept we compare it to the popular “Tiny Habits” methodology. “Tiny Habits” is a habit-forming process developed by B.J. Fogg that builds upon the Fogg Behavior

Model. The concept is as follows. First, the desired behavior is reduced to the smallest possible behavior so it is easily and quickly accomplished. Users with varying degrees

of motivation are now able to cross the activity threshold.

Second, the new tiny habit is positioned to fit easily into a

routine. A signal or reminder in the routine then functions

as a trigger for the habit. Mental constructs are easily

adapted when the habit is triggered within the context of a

routine. Finally, the cycle is repeated until it becomes automated. At this point the habit is developed. The classic

example is flossing. If you don't floss regularly, the task of

flossing all of your teeth (approximately thirty-two teeth!)

takes a lot of effort. Instead, it is made easier by shrinking

the habit to a ridiculously simple task - flossing one tooth.

Then you just floss it at a convenient time - in the morning

after you brush your teeth. The completion of brushing is

the timed trigger for flossing. Over time, you repeat this

and eventually you move up to two teeth, then five, then

twelve, and eventually all thirty-two.

There are three main differences between the tiny habits

and trigger piggybacking methodologies: deliberateness,

scope, and behavior adoption time.

In the Tiny Habits methodology the behavior and behavior forming cycle are focused and deliberate. Designers reduce the needed ability level and place the trigger at a specific time and request the completion of a simple task. The

cycle starts at a designated time and ends just as promptly.

The algorithmic approach to timing and task removes any

3 Step Design Process for

Trigger Piggybacking

Previously, we illustrated and defined trigger piggybacking

through various examples and comparisons to other design

methodologies. In this section, we present a generalized 3step process for designing a trigger piggybacking system.

The process described was built through insights gained

through case study. To concretize the process and provide

an example, we applied the steps to an example case: encouraging students to be accountable for each other’s safety when walking home alone.

81

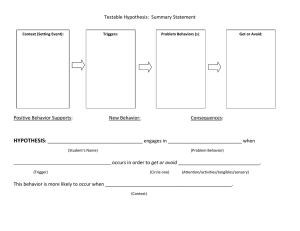

Figure 3 illustrates a way to visualize the Trigger piggybacking methodology. The box labeled “Value” is the initial value system inherent to the problem and the trigger;

the box labeled “Desired Value” is the value that the designer wishes to impart upon the user. The lines at the

topmost of the chart are the set of triggers that can connect

the two value systems. The lines at the bottommost of the

chart are the set of behaviors that are triggered and connect

the two value systems. The bold arrows represent the desired trigger and behavior. The trigger initializes the feedback loop and cues the desired behavior to be performed.

reached home.

Step Three - create trigger:

Finally we need to create the trigger. The trigger should

embody the value system defined in step two. This is the

most difficult and creativity-intensive step in the process.

Example continued:

There are several triggers that can represent friendship.

In our example we choose bumping fists or shaking hands,

both viable gestures and triggers of friendship. Bumping

phones could proxy for bumping fists and act as a mechanism for connecting to mobile phone through the popular

bump libraries for smartphones. With this trigger we successfully transfer the concept of friendship from analog to

digital world and as designers expect user’s to treat in-app

friends with the care and concern as they treat real friends.

Such a trigger sets in motion the multiplicity of desired behaviors and trigger feedback discussed in Figure 3.

Conclusion

The power of triggers that encapsulate value systems is

that they encourage a gamut of desirable behaviors. Instead

of causing only a behavior these triggers activate the intrinsic motivations of the individual and allow them to express their philosophies via behaviors. Over the long term,

triggers that allow individuals express these philosophies

also augment them. In general, Shikake principles should

be applied when users have a latent value or philosophy

that can be piggybacked on. Because of the social nature of

digital interactions, trigger piggybacking is an effective

method for migrating value from the real world to the digital world.

Figure 3: Behavior Multiplicity and Trigger Feedback

Step One - Problem Definition:

To effectively change behavior, the various dimensions

of the problem must be well defined. Key steps are: identification of offending behavior and the enabling behaviors,

understanding user(s) in the realm of the problem and social context (culture), and evaluating the value systems underpinning the problem.

Example:

For the example case, an offending behavior would be

the lack of proactive communication between a pair of

friends. This behavior stems from different behaviors

unique to each individual; laziness, invincibility, apathy. A

characteristic of the student is eagerness for social acceptance, or cherishing friendship.

Step Two - Define target behavior & value system:

Next the designer defines and selects the target value

system, which are likely to compel users to engage in desirable behaviors. Here the designer requires an understanding of the user group to predict whether user behavior

in response to the target value system is desirable.

References

Fogg, B.J. 2002. Computers as Social Actors. Ubiquity 2002(12):

89-120.

Fogg, B.J., Cuellar, G., and Danielson, D. 2002. The humancomputer interaction handbook: fundamentals, evolving technologies and emerging application: Motivating, Influencing, and

Persuading Users. Hillsdale, New J.: CRC Press

Fogg, B.J. 2009. A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design. In

Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Article 4. New York, New York: ACM.

Naohiro Matsumura. 2007. Field Mining: Reconstructing Relations between Human, Objects, and Environment, Proc. First International Symposium on Universal Communication, 153-156.

Nass, C., Steuer, J., and Tauber, Ellen. 1994. Computers are Social Actors. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems. 72-78, New York, New York:

ACM.

Takeuchi, Y., Katagiri, Y., Nass, C., and Fogg, B.J. 2000. A Cultural Perspective in Social Interface. In Proceedings of the CHI

2000 Conference (submitted).

Example continued:

Having identified friendship as the key value, we would

like our students to be accountable and responsible to one

another. Assuming the product is a mobile application, we

want the students to view the other friend’s location via the

mobile application and check for when the other has

82