Internet Gaming Alert U.S. Criminal Jurisdiction and Foreign Internet-Gaming Operations Introduction

advertisement

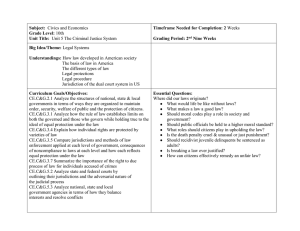

Internet Gaming Alert August 2007 Authors: Linda J. Shorey +1.717.231.4510 linda.shorey@klgates.com Fred D. Heather +1.310.552.5015 fred.heather@klgates.com Anthony R. Holtzman +1.717.231.4570 anthony.holtzman@klgates.com K&L Gates comprises approximately 1,400 lawyers in 22 offices located in North America, Europe and Asia and represents capital markets participants, entrepreneurs, growth and middle market companies, leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100 global corporations and public sector entities. For more information, please visit www.klgates.com. www.klgates.com U.S. Criminal Jurisdiction and Foreign Internet-Gaming Operations Introduction Internet gaming is big business. Every day, massive quantities of money change hands as gaming aficionados around the world go online in pursuit of the thrill of the bet, the challenge of competition and, perhaps, dreams of quick wealth. Internet-gaming entities have realized enormous profits. However, as the events of the past year demonstrate, to the extent that those entities accept wagers from U.S.-based bettors, they and those associated with them face a notable obstacle. The U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) takes the position that all forms of wagers placed over the Internet from the U.S. are covered by the federal Wire Act, 18 U.S.C. §1084, a criminal statute that prohibits anyone who is in the business of betting or wagering from knowingly using a wire device to transmit bets or wagers or related information in interstate or foreign commerce. Many Internet-gaming entities are incorporated and licensed in countries where Internet gaming is legal and are owned or operated by individuals who are not U.S. citizens. Some of these Internet-gaming entities continue to target the lucrative U.S. market, notwithstanding the DOJ’s position and its activities during the past year. This article considers the circumstances under which U.S. federal courts might have jurisdiction to entertain charges brought against foreign Internet-gaming entities and their non-U.S. owners, operators, officers or directors. To hear claims asserted against any entity or person, a U.S. federal court must have both subject matter and personal jurisdiction. This article considers two jurisdictional questions: (1) would a federal court have subject matter jurisdiction over a criminal action alleging a violation of the Wire Act by a foreign Internet-gaming entity and its non-U.S. owners, officers, and directors, and (2) would it have personal jurisdiction over the entity and its owners, officers, and directors? Subject Matter Jurisdiction Applicable principles and law International law recognizes five traditional principles under which a court may assert subject matter jurisdiction over a criminal action – territorial; nationality; universality; passive personality; and protective. These principles were developed by Harvard University researchers in 1935. Many U.S. federal courts, to some extent, have embraced them and use them in determining whether they have subject matter jurisdiction over criminal actions with international features. The law, however, is still developing in this area, particularly with regard to cases in which the alleged criminal activity is legal in the jurisdiction where the defendant resides. And U.S. federal courts do not always address jurisdiction in their opinions, even when international features are present. Under the territorial principle, a federal court has subject matter jurisdiction if the crime was committed in the U.S. Under the nationality principle, a federal court has subject matter jurisdiction if the person accused of committing the crime is a U.S. citizen. Under An abbreviated version of this article appeared in the June 2007 issue of the World Online Gambling Law Report. Internet Gaming Alert the universality principle, a federal court has subject matter jurisdiction if the U.S. has physical custody of the person accused of committing the crime and the crime is considered particularly heinous and harmful to humanity. Under the passive personality principle, a federal court has subject matter jurisdiction if the victim of the crime is a U.S. citizen. Under the protective principle, a federal court has subject matter jurisdiction if the crime threatens the security of the U.S. as a nation or the operation of its governmental functions, and the conduct constituting the crime is generally recognized as criminal under the law of countries that have reasonably developed legal systems. In addition to the above five principles, many U.S. federal courts have adopted a sixth principle – the objective territorial principle. Under this principle, a federal court has subject matter jurisdiction over a criminal action if the criminal conduct in question occurred outside the U.S. but was intended to produce, and did produce, “detrimental effects” within the U.S. The objective territorial, territorial, and nationality principles are those that have most commonly been used by U.S. federal courts as bases for asserting subject matter jurisdiction. Federal courts, in considering whether they have subject matter jurisdiction, should first take into account the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Bowman, 260 U.S. 94 (1922). In Bowman, the Court determined that although the U.S. Congress has power to proscribe criminal conduct committed overseas, a federal court should not conclude that Congress has done so unless the statute that was allegedly violated reflects an intent to do so: “If punishment…is to be extended to include those [acts] committed outside of the strict territorial jurisdiction, it is natural for Congress to say so in the statute, and failure to do so will negative the purpose of Congress in this regard.” Id. at 98. In other words, if a U.S. crime is committed outside the U.S., a federal court does not have subject matter jurisdiction over any affiliated criminal action unless the relevant criminal statute was intended by Congress to reach activity that occurs outside the U.S. Application in connection with the Wire Act A U.S. federal court might find that it has subject matter jurisdiction over a criminal action brought by the U.S. against an offshore Internet-gaming entity and its non-U.S. owners, officers, and directors that alleges a violation of the Wire Act as a result of the entity having accepted bets from U.S.-based bettors. The relevant provision of the Wire Act, 18 U.S.C. §1084(a), provides: Whoever being engaged in the business of betting or wagering knowingly uses a wire communication facility for the transmission in interstate or foreign commerce of bets or wagers or information assisting in the placing of bets or wagers on any sporting event or contest, or for the transmission of a wire communication which entitles the recipient to receive money or credit as a result of bets or wagers, or for information assisting in the placing of bets or wagers, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both. The Wire Act also contains a “safe harbor” provision, 18 U.S.C. §1084(b), which provides: Nothing in this section shall be construed to prevent the transmission in interstate or foreign commerce of information for use in news reporting of sporting events or contests, or for the transmission of information assisting in the placing of bets or wagers on a sporting event or contest from a State or foreign country where betting on that sporting event or contest is legal into a State or foreign country in which such betting is legal. As the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit noted, the safe harbor provision “[b]y its plain terms… requires that betting be ‘legal,’ i.e., permitted by law, in both jurisdictions.” United States v. Cohen, 260 F.3d 68, 73 (2d Cir. 2001). Reading subsection (a) in conjunction with subsection (b) reveals that the Wire Act criminalizes the knowing use of a wire communication facility to transmit bets or wagers or betting-related information between a foreign country and a U.S. state if Internet gaming is illegal in one or both jurisdictions. Because Congress included the term “foreign country” in the Wire Act and made certain transmissions between foreign countries and the several states unlawful, a federal court might conclude that Congress intended for the Wire Act to proscribe conduct committed outside the U.S. If the court did so, it might then invoke an international law August 2007 | Internet Gaming Alert basis for asserting subject matter jurisdiction over a criminal action alleging that the Wire Act was violated as a result of conduct that occurred outside the U.S. The objective territorial principle might serve as a plausible basis if the criminal action alleged that a foreign Internet-gaming entity and its foreign owners, officers, and directors, operating from a foreign nation, violated the Wire Act by using a wire communication facility to transmit online-betting offers or information assisting in the placement of online bets to the residents of a state in which Internet wagering is illegal. The court might arguably have jurisdiction for the reason that, while the alleged criminal conduct (i.e. the sending of online-betting offers or information assisting in the placement of online bets) conceivably occurred outside the U.S., it was arguably intended to produce, and did produce, “detrimental effects” within the U.S. (i.e., the receipt of offers to place bets or the placement of bets). The territorial principle might also be used as a basis for subject matter jurisdiction. In this regard, the court might construe the “transmission” of the online bets as having occurred inside the borders of the U.S. at the moment the bets were placed on the website of the foreign Internet-gaming entity. Such a construction might support the conclusion that the crime was committed (at least partially) in the U.S. and would appear to be consistent with case law from several U.S. federal Courts of Appeals providing that, for purposes of the Wire Act, an individual transmits an online bet if he sends or receives it. In applying either principle, the court would need to take into account the broad international law principle that a court should not exercise subject matter jurisdiction when doing so would be unreasonable. In this regard, reasonableness is determined by weighing a nonexclusive list of factors, including the strength of the link between the conduct in question and the country under whose law the conduct is being prosecuted, the foreseeable effects of the conduct in that country, the character of the conduct, and the extent to which criminalization of the conduct is consistent with the patterns and practices of the international system. See United States v. Davis, 767 F.2d 1025, 1037 n.22 (2d Cir. 1985); Restatement (third) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States §403(2). Given that many countries, including the U.K., license and regulate Internet wagering, this is an important concept. A recent federal criminal indictment and activities related to it demonstrate how the jurisdictional issues can arise. The indictment was issued in June 2006 by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri against BetonSports Plc (a publicly-traded company on the London AIM with operations in Costa Rica), its now-former CEO (a U.K. citizen), and its former owner (a U.S. citizen residing outside the U.S.), among others. The CEO was arrested in July 2006 as he changed planes in Dallas en route to Costa Rica. The former owner was arrested in March 2007 by local officials in the Dominican Republic and turned over to U.S. authorities in Puerto Rico. The indictment alleges violations of a host of federal criminal statutes, including the Wire Act. The individual defendants pleaded not guilty and filed motions to dismiss. The now-former CEO was released on $1 million bail but confined to the jurisdiction of the court. Bail was refused to the former owner, whom the court considered to be a flight risk. While BetonSports reportedly took the position that the court lacked jurisdiction, BetonSports, in June 2007, entered into a plea agreement with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for Eastern Missouri, pursuant to which it pleaded guilty to one count and agreed to cooperate in the USAO’s prosecution of the other defendants. The USAO agreed to recommend dismissal of another count and not to charge BetonSports with any additional crimes related to the activity detailed in the indictment. But the USAO specifically pointed out that the agreement did not extend to any other U.S. Attorney Offices. These activities suggest that at least some federal courts might be willing to assert subject matter jurisdiction over criminal actions against foreign Internet-gaming entities or their owners, officers, or directors, alleging violations of the Wire Act. Personal Jurisdiction A U.S. federal court has personal jurisdiction over an accused criminal who is a resident of a foreign nation only if the accused is present in the court’s territorial jurisdiction. If the accused is not present, the court can seek to secure his presence by requesting formal extradition pursuant to a treaty. An extradition treaty is an instrument that facilitates the surrender of accused criminals from one nation I n United States v. Alvarez-Machain, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that, under some circumstances, a federal court has personal jurisdiction over a foreign criminal defendant even if the defendant was forcibly abducted from the foreign nation where he resides and brought within the territorial jurisdiction of the court. 504 U.S. 655 (1992). August 2007 | Internet Gaming Alert to another. Generally, a nation will only extradite an accused criminal residing within its borders to another nation if the other nation would likewise, under similar circumstances, surrender an accused criminal to the first. A U.S. federal court that requests extradition can obtain personal jurisdiction over the accused criminal only after he is arrested in the nation where he resides and removed to the territorial jurisdiction of the court. Traditionally, the signatory nations to an extradition treaty are only required to surrender individuals who are accused of committing the crimes enumerated in the treaty. A federal statutory provision, 18 U.S.C. §3184, sets forth the process that a court is to use to effectuate the extradition of an accused foreign criminal: Whenever there is a treaty or convention for extradition between the United States and any foreign government…any justice or judge of the United States, or any magistrate judge authorized so to do by a court of the United States, or any judge of a court of record of general jurisdiction of any State, may, upon complaint made under oath, charging any person found within his jurisdiction, with having committed within the jurisdiction of any such foreign government any of the crimes provided for by such treaty or convention…issue his warrant for the apprehension of the person so charged, that he may be brought before such justice, judge, or magistrate judge, to the end that the evidence of criminality may be heard and considered. If the extradition process is implicated, the relevant extradition treaty and laws of the jurisdiction from which extradition is sought will be of great importance and should be carefully reviewed. All individuals arriving in the U.S. via airplane from a foreign country must have a passport. The airlines record those passport numbers. If a federal arrest warrant has been issued for a non-U.S. citizen, an airport is a likely place for the individual to be detained and then arrested. In such a situation, personal jurisdiction might be obtained as a result of the individual’s travel choice. Conclusion The DOJ’s interpretation of the Wire Act and the arrests of foreign nationals at U.S. airports have not discouraged all foreign Internet-gaming entities from offering Internet wagering opportunities to individuals located in the U.S. They are presumably motivated by the money that U.S.-based bettors spend. Prior to June 2006, many may never have thought that a U.S. federal court could assert subject matter jurisdiction over a criminal action against them, or be able to obtain personal jurisdiction over them or their owners, officers, or directors. That mode of thinking has been modified with the indictment of BetonSports and its now-former CEO. The DOJ has also demonstrated that it is willing to arrest non-U.S. citizens who are owners, officers, or directors of Internet-gaming entities if they travel to or through the U.S. The law with respect to jurisdiction in these situations is not settled, and there are arguments that can be made in specific situations as to why subject matter or personal jurisdiction does not exist. But, at this time, the risk of arrest and detention is real. This article is for informational purposes only and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon with regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Of course, as the arrest of the CEO of BetonSports shows, personal jurisdiction can be obtained over nonU.S. citizens who travel to or through the U.S. by virtue of their voluntary physical presence in the U.S. A ccording to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, “when personal jurisdiction over a criminal defendant is obtained through extradition proceedings, the defendant may invoke the provisions of the relevant extradition treaty in order to challenge the court’s exercise of personal jurisdiction.” United States v. Puentes, 50 F.3d 1567, 1573 (11th Cir. 1995). Some of the other eleven U.S. Courts of Appeals, however, have concluded that only the country where the accused individual resides has standing to challenge the court’s exercise of personal jurisdiction. See, e.g., Shapiro v. Ferrandina, 478 F.2d 894 (2d Cir. 1973). August 2007 | Internet Gaming Alert K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated partnerships: a limited liability partnership with the full name Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP qualified in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the U.S., in Berlin, and in Beijing (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP Beijing Representative Office); a limited liability partnership (also named Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining our London office; a Taiwan general partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis) which practices from our Taipei office; and a Hong Kong general partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis, Solicitors) which practices from our Hong Kong office. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office. This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Data Protection Act 1998—We may contact you from time to time with information on Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP seminars and with our regular newsletters, which may be of interest to you. We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail london@klgates.com if you would prefer not to receive this information. ©1996-2007 Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP. All Rights Reserved. August 2007 |