Rotational friction on small globular proteins: Combined dielectric and hydrodynamic effect

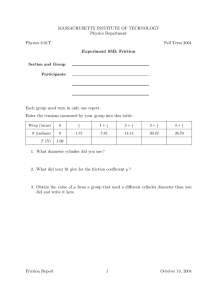

advertisement

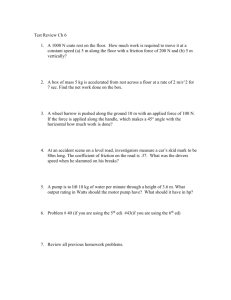

Rotational friction on small globular proteins: Combined dielectric and hydrodynamic effect Arnab Mukherjee and Biman Bagchi ∗ arXiv:physics/0408071 v1 15 Aug 2004 Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India 560 012. Abstract Rotational friction on proteins and macromolecules is known to derive contributions from at least two distinct sources – hydrodynamic (due to viscosity) and dielectric friction (due to polar interactions). In the existing theoretical approaches, the effect of the latter is taken into account in an ad hoc manner, by increasing the size of the protein with the addition of a hydration layer. Here we calculate the rotational dielectric friction on a protein (ζDF ) by using a generalized arbitrary charge distribution model (where the charges are obtained from quantum chemical calculation) and the hydrodynamic friction stick with stick boundary condition, (ζhyd ) by using the sophisticated theoretical technique known as tri-axial ellipsoidal method, formulated by Harding [S. E. Harding, Comp. Biol. Med. 12, 75 (1982)]. The calculation of hydrodynamic friction is done with only the dry volume of the protein (no hydration layer). We find that the total friction stick obtained by summing up ζDF and ζhyd gives reasonable agreement stick with the experimental results, i.e., ζexp ≈ ζDF + ζhyd . ∗ Email: bbagchi@sscu.iisc.ernet.in 1 1 Introduction In this article, we present an interesting result that the experimentally observed rotational correlation time of a large number of proteins can essentially be described as the combined effect of the rotational dielectric and hydrodynamic frictions on the proteins. Thus, one needs not assume the existence of a rigid hydration layer around the protein, as is often assumed in the standard theoretical calculations of hydrodynamic friction. The study of rotational friction of proteins in aqueous solution has a long history [1−12]. Despite many decades of study, several aspects of the problem remain ill understood. For proteins and macromolecules, the rotational friction is obtained from Debye-Stokes-Einstein (DSE) relation given by, ζR = 8πη R3 , (1) where ζR is the rotational friction on the protein and R is the radius of the protein. Naturally, the above relation assumes a spherical shape of the protein, which is often not correct. Moreover, there is ambiguity about the determination of some average radius of the protein. If one obtains the radius from the standard mass density of the protein (0.73 gm/cc), the values of the rotational friction are much smaller. The dielectric measurement of Grant [4] showed that the experimental value of rotational friction of myoglobin could only be explained by the above DSE equation, if one assumes a thick hydration layer around the protein, thereby increasing the radius of the protein. It is well known that spherical approximation embedded in DSE is grossly in error and the shape of the protein is quite important. However, even with the more recent sophisticated techniques such as tri-axial ellipsoid method [5] and the microscopic bead modeling technique [6, 7], which take due recognition of the non-spherical shape of the macromolecule, agreement with the experimental result is not possible without the incorporation of a rigid hydration layer [10]. In should be recognized that the effect of hydration layer thus introduced is purely ad hoc. In the case of tri-axial ellipsoidal method, the values of the axes are 2 increased proportionately by increasing the percentage of encapsulation of the protein atoms inside its equivalent ellipsoid [11, 12]. On the other hand, the microscopic bead modeling technique uses beads of much bigger size [6] (3.0 Å instead of 1.2 Å) to take care of the effect of hydration layer. Without the hydration layer, the estimate of friction obtained from the theory is systematically lower. It has been recognized quite early that water in the hydration layer surrounding proteins and macromolecules has completely different dynamical properties than those in the bulk [13]. The dynamics of water molecules in the hydration layer are also subject of great interest as they could play crucial role in the property and activity of these molecules. One often discusses the crossover from biological activity to the observed inactivity at low temperatures in terms of a proteinglass transition observed in the hydrated proteins [14]. Recent investigations have shown that the water molecules in the hydration layer are not only more structured but they also show slow translational and rotational motion than their bulk counterpart [15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that water molecules in the surface of a protein such as myoglobin are so slow that we can replace it by a rigid hydration layer. On the contrary, all the recent experimental and simulation studies have shown that the water in the surface of the protein exhibits bimodal dynamics [20]. Majority of the water molecules seem to retain their bulk-like dynamics while a fraction (∼ 20%) exhibits markedly slow dynamics. Recent solvation dynamics and photon echo peak shift experiment not only established the existence of slow water on the surface of proteins but also showed that the hydration layer is quite labile [21]. If one defines an average residence time to characterize the dynamics of water in the hydration layer, the residence time of bound or quasi-bound water is expected to range from 20 to 300 ps [22]. Question naturally arises how to understand quantitatively the role of the hydration layer in enhancing the rotational friction on the protein molecules. Clearly, the picturesque description of an immobile rigid layer around protein needs to be replaced by a description where the hydration layer is slow but definitely 3 dynamic. This labile hydration layer has been explained in terms of a dynamic exchange model, which assumes that due to the presence of relatively stronger hydrogen bonding of water molecules with the charged groups at the surface of the protein, a surface water molecule can exist in either of the following two states – bound and free [23]. The free water molecules have dynamical characteristics similar to those of the bulk but the bound water molecules are essentially made static by the hydrogen bonding with the surface. In this picture, the slow time scale arises due to the dynamical exchange between the two states of the water molecules. Recent computer simulations seem to have confirmed the essential aspects of the dynamic exchange model (DEM) [24]. While the above model can provide a simple explanation of the origin of the observed slow dynamics, its correlation with dynamical properties of protein has not yet been established. This is a non-trivial problem as discussed below. The mode coupling theory (MCT) is another viable quantitative theory, which has been quite successful in describing translational and rational motion of small molecules [25]. This approach has also been extended to treat dynamics of polymer and biomolecules [26]. Let us recall a few of the lessons learned from the MCT of rotational friction of small molecules, and translational friction of ions in dipolar liquids. In both the cases, intermolecular dipole-dipole/ion-dipole correlations were found to play important role. It was also found that if one neglects the translational mode of the solvent molecules, then the friction on polar solute increases by several factors. It should be noted here that the continuum models/hydrodynamic description of rotational friction always ignored this translational component. In fact, this translational component plays a hidden role in reducing the effect of the role of molecular level solute solvent and solvent-solvent pair (both isotropic and orientational) correlations that increase the value of the friction over the continuum model prediction. Thus, the issue is rather involved. In fact, the continuum model is found to give ac4 curate results due to cancellation of two errors: neglect of short-range correlations and neglect of translational contribution. In view of the above, it is thus important to note that the slow water molecules in the hydration layer can enhance the friction considerably. Thus, the classical picture of rigid, static hydration layer needs to be replaced by dynamic layer where the translational motion of the water molecules should be related to the residence time. However, only preliminary progress has been made in this direction. Thus, continuum models remain the only theoretical method to treat dielectric friction on complex molecules. An important issue in the calculation of the rotational friction is that proteins are characterized by complex charge distribution. The earliest models to estimate the enhanced friction on a probe, due to the interactions of its polar groups with the surrounding water molecules in an aqueous solution, employed a point dipole approximation [27, 28, 29]. In the simplest version of the model, the probe molecule is replaced by a sphere with a point dipole at the center of the sphere. Such an approach is reasonable for small molecules, although continuum model itself may have certain limitations. The situation is quite different for large molecules like proteins because the charge here is distributed over a large volume and the surface charges are close to the water molecules. Thus, the point dipole approximation becomes inapplicable to such systems. This limitation of the early continuum models was removed by Alavi and Waldeck [30] who obtained an elegant expression for the dielectric friction on a molecule with extended arbitrary charge distribution. By studying several well-known dye molecules, they demonstrated that the extended charge distribution indeed has a strong effect on the dielectric friction on the probe molecules. The work of Alavi and Waldeck [30] constitutes an important advance in the study of dielectric friction. The role of dielectric friction has been studied for the organic molecules by other authors [31]. The objective of the present work is to attempt to replace the rigid hydration layer used in hydrodynamic calculation. To this goal, we 5 calculate the hydrodynamic friction using the tri-axial method [5], in which the shape of a protein is mapped to an ellipsoid of three unequal axes – closely representing the shape and size of the protein. No hydration layer is added in the calculation. We then calculate the dielectric friction using Alavi and Waldeck’s model of generalized charge distribution for a large number of proteins. The friction contributions obtained from the above two methods are combined to obtain the total rotational friction. When compared, the total friction has been found to agree closely with the experimental result. We have also extended the work of Alavi and Waldeck to include multiple shells of water with different dielectric constants around a protein. The multiple shell model is introduced in concern with the experimental observation of varying dielectric constants of water from the hydration layer surrounding a protein to the bulk water. These shells have distinct dielectric properties – both static and dynamic. The resulting analytical expressions can be used to obtain quantitative prediction of the effects of a slow layer of water molecules on the dielectric friction on proteins. However, the multiple shell model in the continuum fails since it adds up the friction in every layer. This has been discussed in the appendix. 2 Results and Discussion Below, we discuss the results obtained from the different aspects of rotational friction of proteins. The coordinates of the proteins are obtained from protein data bank (PDB) [32]. 2.1 Dielectric Friction Dielectric friction is an important part of rotational friction for polar or charged molecules in polar solvent, because of the polarization of the 6 solvent medium. The solvent molecules, being polarized by the probe, create a reaction filed, which opposes the rotation of the probe. Many of the amino acid residues, which constitute the protein, are polar or hydrophilic. Therefore, in the aqueous solution, a protein and other polar molecules experience significant dielectric friction. There exist several theories [27, 28, 29, 33, 34, 35], which account for the dielectric contribution to the friction. Some of these theories are continuum model calculation of a point charge or point dipole rotating within the spherical cavity. Nee and Zwanzig [27] provide an estimate of dielectric friction on a point dipole in terms of the dipole moment of the point dipole, dielectric constant of the solvent, Debye relaxation time, and the chosen cavity radius. Later, Alavi and Waldeck [30] extended this theory to incorporate the arbitrary multiple charge distribution of the probe molecule. The dielectric friction on the proteins has been calculated from the expression of Alavi and Waldeck for arbitrary multiple charge distribution model given below [30], ζDF l 2l + 1 (l − m)! ∞ X N X N X X ri l rj l 8 ǫs − 1 × τD qi qj = Rc (2ǫ1 + 1)2 j=1 i=1 l=1 m=1 l + 1 (l + m)! Rc Rc m2 Plm (cos θi ) Plm (cos θj )cos(mφji ) where Rc is the cavity radius, (ri, θi, φi) is the position vector and qi is the partial charge of the ith atom. Plm (cos(θi) is the Legendre polynomial. The maximum value of l used in the Legendre polynomial is 50. ǫs is the static dielectric constant of the solvent. Since the solvent here is water, ǫs is taken to be 78 and the Debye relaxation time τD is taken as 8.3 picosecond (ps). The partial charges (qi) of the atoms constituting the proteins have been calculated using the extended Huckel model of the semi empirical calculation package of Hyperchem software. The dielectric friction is calculated on each of the atoms in a protein. The rotational frictions around X, Y and Z direction are calculated by changing the labels av is the of the atom coordinates. The average dielectric constant ζDF 7 (2) harmonic mean of the dielectric frictions along X, Y and Z direction. Here X, Y, and Z denote the space fixed Cartesian coordinate of the proteins, as obtained from PDB [32]. Table 1 shows the values of dielectric friction along X, Y, Z direction and their average. Continuum calculation method of the dielectric friction formulated by Alavi and Waldeck is dependent on the cavity radius and has been discussed in detail by them [30]. They calculated the cavity radius from the observed orientational relaxation time of the organic molecules. The ratios of the longest bond vector of the organic molecules to the cavity radius ranged from 0.75 to 0.85. In Table 1, the calculation s of dielectric friction are performed using the cavity radius such that the ratio of the longest bond vector to the cavity radius is 0.75. In Table 2, we compared the average dielectric friction for the two 0.85 0.85 0.75 ). ζDF ) and 0.85 (denoted as ζDF above ratios – 0.75 (denoted as ζDF 0.75 is always larger than ζDF since the shorter cavity radius will put the charges close to the surface of the cavity, thereby increasing the polarization of the solvent and hence the rotational friction of the molecule. 2.2 Hydrodynamic Friction The hydrodynamic rotational friction of the protein depends on its shape and size. Hydrodynamic friction was estimated earlier by the well-known DSE relation (Eq. 1). Perrin in 1936 [36] extended the DSE theory to calculate the hydrodynamic friction for molecules with prolate and oblate like shapes. Both prolate and oblate have two unequal axes. Harding [5] further extended the theory to calculate the hydrodynamic friction using a tri-axial ellipsoid. All the above theories employ stick binary condition to obtain the hydrodynamic friction. Tri-axial ellipsoidal technique requires the construction of an equiv8 alent ellipsoid of the protein. We have followed the method of Taylor et al. to construct an equivalent ellipsoid from the moment matrix [37]. The eigenvalues of this equivalent ellipsoid are proportional to the square of the axes. So this method provides with the two axial ratios. We then obtained the values of the axes using the formula given by Mittelbach [38] 1 (3) Rγ2 = (A2 + B 2 + C 3) 5 Rγ is the radius of gyration and A, B and C are the three unequal axes of a particular protein. Once the protein is represented as an ellipsoid with three principle axes, the hydrodynamic friction is calculated using Harding’s method [5, 39]. The hydrodynamic rotational friction of the ellipsoidal axes A, B and C are denoted as ζA , ζB and ζC . The above rotational friction is obtained from the series of equations given below [39], ζ0 = 8πηABC, 2(B 2 + C 2) ζA = ζ0 , 3ABC(B 2α2 + C 2α3 ) 2(A2 + C 2) , ζB = ζ0 3ABC(A2α1 + C 2α3 ) 2(A2 + B 2) ζC = ζ0 , 3ABC(A2α1 + B 2 α2 ) Z ∞ dλ , α1 = 0 (A2 + λ)∆ Z ∞ dλ , α2 = 0 (B 2 + λ)∆ Z ∞ dλ , α1 = 0 (C 2 + λ)∆ 2 2 2 ∆ = (A + λ)(B + λ)(C + λ) 9 1 2 (4) η is the viscosity of the solvent. We have calculated the average of triaxial hydrodynamic friction by taking a harmonic mean of the friction along three different axes, as given below, 1 ζTavR 1 1 1 1 = + + 3 ζTAR ζTBR ζTCR (5) The values of hydrodynamic friction, along three principle axes (A, B and C) of the ellipsoid and their mean, are tabulated in the Table 3. The A, B and C axes are not the same as the space fixed X, Y, Z Cartesian reference frame. Note that the values obtained from the tri-axial method are much lower than the experimental values. Here, we can talk about an important aspect of standard hydrodynamic approach – hydration layer. One finds that hydrodynamic values of rotational friction underestimate the rotational friction unless the effect of hydration layer is taken into account. However, the effect of hydration layer is usually incorporated in an ad hoc manner, by increasing the percentage of encapsulation of the atoms inside the ellipsoid [12, 11]. In this method, once the two axial ratios are obtained from the equivalent ellipsoid, the actual values of the axes are obtained by increasing the encapsulation of the protein atoms inside the ellipsoid. In the calculation presented here, the axes are obtained by equating with the radius of gyration. Therefore, we considered no hydration layer in this calculation of hydrodynamic friction. Later, we will show that this effect of hydration layer comes from the dielectric friction. 2.3 Total rotational friction: Comparison with experimental results We define the total rotational friction as the sum of dielectric friction av (ζDF ) and the hydrodynamic friction without the hydration layer (i.e. tri-axial friction, ζTavR ) as given below, av ζtotal = ζDF + ζTavR 10 (6) av In Table 4, we have shown the values of the average dielectric (ζDF ), av hydrodynamic (ζT R ) friction. Total friction (ζtotal ) defined above is shown in the fourth column. To compare with the experimental results, we have shown the experimental values of the rotational friction in the next column. Note here, while the total friction, which is the contribution from both dielectric and hydrodynamic friction, is close to the experimental result, the microscopic bead modeling predicts the result, which is close to experimental value by itself [7]. The last column of Table 4 shows the references of the articles from which the experimental results are obtained. The similarity between the total friction and the experimental friction is shown in figure 1, where we have plotted the experimental values of rotational friction against the total friction for a large number of proteins. For most of the proteins, the results fall on the diagonal line. From the results shown in Table 4, we can conclude that the sum of dielectric friction and the hydrodynamic friction of the dry protein is approximately equal to the experimental results. ζtotal ≈ ζexp 3 (7) Conclusion Let us first summarize the main results of this work. We have calculated the hydrodynamic rotational friction on proteins using the tri-axial ellipsoid method, formulated by Harding [5], and the dielectric friction using the generalized charge distribution model derived by Alavi and Waldeck [30]. The hydrodynamic friction is calculated without the inclusion of any hydration layer. We have found that the combined effect of dielectric and hydrodynamic friction gives an estimate close to the experimental result. This approach seems to provide 11 a microscopic basis for the standard hydrodynamic approach, where a hydration layer is added to the protein in an ad hoc manner, to calculate rotational friction. The calculations adopted here are still not without limitations. The continuum calculation of dielectric friction is dependent on the assumed cavity radius. Unfortunately, there is yet no microscopic basis to assume certain value of the cavity radius for the calculation of dielectric friction. Moreover, the effect of increasing dielectric constant of the solvent from the vicinity of the protein to the bulk is not taken into account by Alavi and Waldeck [30]. Thus, we have attempted to incorporate a multi shell model to incorporate multiple shells with varying dielectric constants. The theory is described in the appendix in detail. The drawback of incorporation of multiple shells in the continuum is that the frictional contributions from each of the shells add up, thereby giving rise to an unphysical large result. Similarly, the tri-axial method and bead modeling method suffer from the lack of microscopic basis to determine the exact values of the axes and the bead size, respectively. A potentially powerful approach to the problem is the mode coupling theory [40], which uses the time correlation formalism to obtain the memory kernel of the rotational friction. The total torque is separated into two parts – a short range part (which is called the bare friction Γbare ) and a long range dipolar part. The advantage of mode coupling theory is that it does not depend on any parameter. It uses a time dependent effective potential field in terms of density distribution and the direct correlation function given by [40], Vef f (r, Ω, t) = −kB T Z ′ ′ ′ ′ ′ ′ dr dΩ c(r − r , Ω, Ω )∇Ωρ(r , Ω , t) (8) The torque density is then expressed as, Nc (r, Ω, t) = n(r, Ω, t) −∇Ω Vef f (r, Ω, t) (9) where, n(r, Ω, t) is the number density of the tagged particle. The rotational friction comes from the torque-torque correlation function. 12 The final expression of the single particle (Γs) and collective friction (Γc ) are given by [41], Γs (z) = Γbare + Γc (z) = Γbare + A Z Z ∞ −zt ∞ dk A e 0 0 Z ∞ Z ∞ dk e−zt 0 0 k2 k2 X l1 l2 m X l1 l2 m c2l1 l2 m (k)Fl2m (k, t) (10) Fls1m (k, t) c2l1 l2 m (k) Fl2 m (k, t) (11) . cl1 l2 m is the l1 l2m-th coefficient of the two particle where, A = direct correlation function between any two dipolar molecules. Fls1 l2 m and Fl2 m (k, t) are the single particle and the collective orientational correlation functions, respectively. ρ 2 (2π)4 Eq. 10 and Eq. 11 are the standard mode coupling theory expressions for rotational friction. It has to be solved self consistently. In the overdamped limit, the self dynamic structure factor is expressed as, kB T l(l + 1) −1 s (12) Flm(k, z) = z + IΓs (z) and the collective dynamic structure factor is given by, c Flm = Flm (k) z + kB T fllm(k)l(l + 1) kB T k 2fllm(k) −1 + IΓc (z) MΓT (z) (13) where fllm(k) = 1 − (−1)m(ρ/4π)cllm(k). I and M are the moment of inertia and the mass of the dipolar molecule, respectively. ΓT (z) is the frequency dependent translational friction. The advantage of the mode coupling approach is that the once the charge density of the protein molecules and the dipole density of the water molecules surrounding the protein are defined, the rotational friction can be obtained in terms of the direct correlation function and the static and dynamic structure factors of the protein-water systems. These are again related by Ornstein-Zernike equation [42]. 13 The important aspect of this microscopic theory of dielectric friction is the hidden contribution of the translational modes. In the hydration layer, the rotational friction is enhanced due to the slow translational component. This effect of translation could not be approached through continuum calculation. Work in this direction is under progress. 4 Appendix : Multiple shell model and the Drawback Dielectric constant of water varies from the vicinity of the protein to the bulk water value. To understand the effect of this varying dielectric constant on the rotational dielectric friction of the protein, we have performed the continuum calculation of rotational dielectric friction using a multiple shell model. Nee and Zwanzig derived the dielectric friction contribution of a point dipole [27]. Alavi et al. [30] generalized it to obtain dielectric friction of a molecule with arbitrary distribution of charges. Castner et al. [43] generalized the point dipole approach to incorporate the discrete shell model with varying dielectric constant. Here, we have combined the approach of Castner et al. and Alavi et al. to obtain a generalized arbitrary charge distribution model for multiple hydration layers with varying dielectric constants around the protein. Figure 2 shows the general scheme of this work. The protein is in the innermost cavity of radius a, where the water has a dielectric constant value of 4. The dielectric constant of water in the successive layers is assumed to increase up to the value of the bulk water, having a dielectric constant of 78. The width of each shell is assumed to be d. We first write down the electrostatic potential in two dimensions, which could be generalized to three dimensions using principle of su- 14 perposition. The electrostatic potential Φj (r) can be written as, Φj (r) = Φj (r, θ) = ∞ X Blj l=0 Pl (cos θ) + Ajl rl Pl (cos θ) l+1 r (14) where, j denotes the number of concentric shells surrounding the protein. For n concentric shell, j can have a value from 0 to n + 1. j = 0 denotes no boundary. The boundary conditions are, (i) Bl0 = qi ril , where qi and ri are the partial charge and the position of the ith atom, respectively. (ii) Φ → 0 as r → ∞ (iii)Φj (rj ) = Φj+1(rj+1), for j = 0, 1, 2...n. ′ ′ ′ (iv) ǫj Φj (rj ) = ǫj+1Φj+1(rj ), for j = 0, 1, 2..n, Φj (r) = ∂Φ∂rj (r) . = 0, (v ) An+1 l After incorporating the boundary conditions in Eq. 14, we get, Ajl Blk ǫk+1/ǫk − 1 =− l 2l+1 × ǫk+1/ǫk + l+1 k=j rk n X where, Blj = qi ril 1 2l + 1 j j Πk=1 l+1 ǫk /ǫk−1 + l l+1 (15) (16) The reaction potential is given by, Φj (r, θ, φ) = N X ∞ X i=1 l=0 A0l rl Pl (cos γi ) (17) where, Pl (cos γi) = X 4π m=l Ylm∗ (θi, φi)Ylm (θi, φi) 2l + 1 m=−l (18) After few steps of algebra, we obtain the frequency dependent dielectric friction given below, ζlm (ω) N X N X ∞ X l X 2qiqj ri l rj l × = a a j=1 i=1 l=1 m=1 a ω (l − m)! m Pl (cosθi )Plm (cosθj ) m cos(mφji ) × (l + m)! 15 n X Im a s=0 Πsk=1 1 − a 2l+1 ǫs+1,s(m ω) − 1 × l + sd ǫs+1,s(m ω) + l+1 ǫk,k−1(m ω) − 1 l ǫk,k−1(m ω) + l+1 (19) where, ǫj,j−1 = ǫj /ǫj−1, for all values of j. ǫ0 is the dielectric constant of the cavity. Above is the general expression of multiple (n) shell model. To write the final expression of dielectric friction for a two shell model, we assume Debye relaxation for the frequency dependent dielectric friction of two shells as given below, ǫ1,0(mω) = 1 + ǫ1,0 − 1 1 + i mω τD1 (20) ǫ2,1 − 1 (21) 1 + i mω τD2 are the Debye relaxation time for the first and ǫ2,1(mω) = 1 + where, τD1 and τD2 second shell. The expression of dielectric friction for a two-shell model is given below, ζDF N X N X ∞ X l X l l 8 2l + 1 (l − m)! rj ri × = qi qj l + 1 (l + m)! a a j=1 i=1 l=1 m=1 a m2 Plm (cos θi ) Plm (cos θj ) cos(mφji ) × ǫ1,0 − 1 a 2l+1 ǫ2,1 − 1 τD1 + τD2 (2ǫ1,0 + 1)2 a+d (2ǫ2,1 + 1)2 ǫ2,1 − 1 a 2l+1 ǫ1,0 − 1 × +2 a+d (2ǫ1,0 + 1)2 (2ǫ2,1 + 1)2 (2ǫ1,0 + 1)τD2 + (2ǫ2,1 + 1)τD1 , 16 (22) The above expression has been numerically evaluated to find out the effect of dielectric friction on protein due to varying dielectric constant of water around the protein. The multiple shell model is found to overestimate the dielectric friction, as is evident from the above expression. Acknowledgment The work is supported by DST, DBT and CSIR. A.M. thanks CSIR for Senior Research Fellowship. References [1] G. Fleming, Chemical Applications of Ultrafast Spectroscopy (monograph), (Oxford University Press, 1986). [2] E. H. Grant, Dielectric behaviour of biological molecules in solution, (Oxford University Press, 1978). [3] R. Pethig, Dielectric and electronics properties of biological materials, (John Wiley & Sons, 1979). [4] G. P. South and E. H. Grant, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 328, 371 (1972). [5] S. E. Harding, M. Dampier, and A. J. Rowe, IRCS Med. Sci. 7 33 (1979). [6] J. G. de la Torre, Biophys. Chem. 93, 159 (2001). [7] J. G. de la Torre, M. L. Huertas, and B. Carrasco, Biophys. J. 78, 719 (2000). [8] B. Halle and M. Davidovic, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA), 100, 12135 (2003). [9] H-X. Zhou, Biophys. Chem. 93, 171 (2001) and references therein. [10] B. Carrasco and J. G. de la Torre, Biophys. J. 75, 3044 (1999). 17 [11] S. E. Harding, Biophys. Chem. 93, 87 (2001). [12] J. J. Muller, Biopolymers, 31, 149 (1991). [13] S. Pal, S. Balasubramanian, and B. Bagchi, J. Chem. Phys. 117, 2852 (2002). [14] M. M. Teeter, A. Yamano, B. Stec, and U. Mohanty, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11242 (2001) ; A. L. Tournier, J. Xu and J. C. Smith, Biophys. J. 85, 1871 (2003). [15] S. Pal, J. Peon, B. Bagchi and A.H. Zewail, J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 12376 (2002). [16] A. R. Bizzarri and S. Cannistraro, J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 6617 (2002). [17] M. Marchi, F. Sterpone, and M. Ceccarrelli, J. Am. Chem. Soc. (2002). [18] R. Abseher, H. Schreiber, and O. Steinhauser, Proteins 25, 366 (1996). [19] S. Balasubramanian and B. Bagchi, J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 3668 (2002). [20] E. Dachwitz, F. Parak and M. Stockhausen, Ber. BunsenGes. Phys. Chem., 93, 1454 (1989). S. Boresch, P. Höchtl, and O. Steinhauser, J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 8743 (2000) ; [21] M. Cho, J. Y. Yu, T. Joo, Y. Nagasawa, S. A. Passino and G. R. Fleming, J. Phys. Chem., 100, 11944, (1996) ; S. Passino, Y. Nagasawa and G. R. Fleming, J. Chem. Phys., 107, 6094 (1997). N. Nandi and B. Bagchi, J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 8217 (1998). [22] G. Otting, E. Liepinsh and K. Wüthrich, Science, 254, 974 (1991). ; X. Cheng and B. P. Schoenborn, J. Mol. Biol. 220, 381, (1991) ; V. A. Makarov, B. K. Andrews, P. E. Smith, and B. M. Pettitt, Biophys. J. 79, 2966 (2000). 18 [23] N. Nandi and B. Bagchi, J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 10954 (1997). [24] B. Bagchi, Annu. Rep. Prog. Chem., Sect. C, 99, 127 (2003). [25] J. A. Montgomery, Jr., B. J. Berne, P. G. Wolynes, and J. M. Deutch, J. Chem. Phys. 67, 5971 (1977). [26] P. G. Wolynes, Phys. Rev. A 13, 1235 (1976) ; S. Takada, J. Portman and P. G. Wolynes, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94, 2318 (1997). [27] T-W. Nee and R. Zwanzig, J. Chem. Phys. 52, 6353 (1970). [28] J. B. Hubbard and P. G. Wolynes, J. Chem. Phys. 69, 998 (1978); ; B. Bagchi and G. V. Vijayadamodar, J. Chem. Phys. 98, 3352 (1993) ; J. B. Hubbard, J. Chem. Phys. 69, 1007 ( 1978).; [29] G. van der Zwan and J. T. Hvnes. J. Phvs. Chem. 89,4181 (1985). [30] D. S. Alavi and D. H. Waldeck, J. Chem. Phys. 94, 61196 (1991). [31] G. B. Dutt and T. K. Ghanty, J. Chem. Phys. 116, 6687 (2002) ; ibid 115, 10845 (2001) ; D. S. Alavi, R. S. Hartman, and D. H. Waldeck, J. Chem. Phys. 94 4509, (1991). [32] H. M. Berman, J. Westbrook, Z. Feng, G. Gilliland, T. N. Bhat, H. Weissig, I. N. Shindyalov, P. E. Bourne, Nucleic Acids Research 28 235 (2000) [33] B. U. Felderhof, Mol. Phys. 48, 1269 (1983); ibid 48, 1283 (1983); E. Nowak, J. Chem. Phys. 79 ,976 (1983). [34] P. G. Wolynes, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 31,345 (1980) [35] P. Madden and D. Kivelson, J. Phys. Chem. 86,4244 ( 1982). [36] F. Perrin, J. Phys. Rad. Ser. VII 5, 497 (1934) ; ibid 7, 1 (1936). 19 [37] W. R. Taylor, J. M. Thornton, and W. G. Turnell, J. Mol. Graph. 1, 30 (1983). [38] P. Mittelbach, Acta. Phys. Austriaca. 19 53 (1964). [39] S. E. Harding, Comp. Biol. Med. 12, 75 (1982); ibid, Biophys. Chem. 55, 69 (1995) ; [40] B. Bagchi and A. Chandra, Adv. Chem. Phys. 80, 1 (1991). [41] B. Bagchi , J. Mol. Liq. 77, 177 (1998). [42] C. G. Gray and K. E. Gubbins, Theory of Molecular Fluids, (International Series of Monograps on Chemistry, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1984). [43] E. W. Castner, Jr., G. R. Fleming, B. Bagchi, J. Chem. Phys. 89, 3519 (1988). 20 Table 1 Table for the dielectric friction. The unit is 10−23 erg-sec. Cavity radius is chosen such a way that the ratio of longest bond vector (Rmax) of the protein to the chosen cavity radius (RC ) is 0.75. X Y Z av Molecule RC (Å) ζDF ζDF ζDF ζDF 6pti 29.50 17.8 13.2 18.1 16.0 1ig5 26.10 43.3 36.6 39.1 39.5 1ubq 34.30 18.1 18.3 21.8 19.3 351c 25.50 52.3 41.0 41.9 44.5 1pcs 27.20 90.5 51.3 66.1 65.7 1a1x 33.10 63.0 68.9 49.5 59.3 1gou 32.20 43.8 67.8 103.6 63.5 1aqp 35.30 44.5 71.1 132.1 68.0 1e5y 33.10 98.9 70.6 89.9 84.7 1bwi 35.70 78.3 60.5 108.1 77.8 1b8e 33.50 113.3 112.2 110.5 112.0 4ake 50.30 76.1 170.8 123.4 110.7 3rn3 35.00 118.8 89.0 56.8 80.5 1mbn 28.00 170.7 162.0 160.6 164.3 21 Table 2 Cavity size dependence of the dielectric friction. The unit is 10−23 erg-sec. Molecule 6pti 1ig5 1ubq 351c 1pcs 1a1x 1gou 1aqp 1e5y 1bwi 1b8e 4ake 3rn3 1mbn 6lyz 0.75 ζDF 16.4 39.7 19.4 45.1 69.3 60.5 71.7 82.6 86.5 82.3 112.0 123.4 88.2 164.5 107.8 22 0.85 ζDF 25.7 61.3 30.3 69.3 111.0 96.4 114.6 132.3 136.4 128.9 174.1 211.7 138.1 263.1 172.7 Table 3 Table for the stick hydrodynamic friction using tri-axial ellipsoid. The unit is 10−23 erg-sec. Molecule Rγ (Å) 6pti 11.34 1ig5 11.36 1ubq 11.73 351c 11.51 1pcs 12.38 1a1x 13.47 1gou 13.61 1aqp 14.45 1e5y 13.81 1bwi 13.94 1b8e 14.70 4ake 19.59 3rn3 14.31 1mbn 15.25 ζTAR 57.8 72.9 71.2 77.3 78.9 120.8 103.3 117.7 108.9 106.9 167.5 298.3 112.9 163.7 23 ζTBR 83.4 78.9 89.9 84.5 106.5 127.3 141.7 171.1 145.7 155.4 172.5 422.7 166.5 181.2 ζTCR 85.1 84.9 94.0 85.3 111.3 143.8 148.2 177.0 155.3 158.2 178.2 442.8 172.2 210.1 ζTavR 73.1 78.6 83.8 82.2 96.6 129.9 127.7 150.1 133.4 135.7 172.6 376.1 145.1 183.1 Table 4 Comparison between the total friction and the experimental results. Results are given in the unit of 10−23 erg-sec. The references to the experimental results of rotational diffusion of the corresponding proteins are given in the Ref. [8] . av Protein PDB id ζDF ζTavR ζtotal ζexp Bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor 6pti 16.0 73.1 89.1 96.8 Calbindin D9k, holo form 1ig5 39.5 78.6 118.1 125.0 Human ubiquitin 1ubq 19.3 83.8 103.1 118.9 Ferricytochrome c551 351c 44.5 82.2 126.7 130.1 Plastocyanin, Cu(II) form 1pcs 65.7 96.6 162.3 149.5 M T CP 1 Oncogenic protein p13 1a1x 59.3 129.9 189.2 241.9 Binase 1gou 63.5 127.7 191.2 191.3 Ribonuclease A 1aqp 68.0 150.1 218.1 186.1 Azurin, Cu(I) form 1e5y 84.7 133.4 218.1 190.4 Hen egg-white lysozyme 1bwi 77.8 135.7 213.5 203.6 Bovine -lactoglobulin, monomer 1b8e 112.0 172.6 284.6 270.6 Adenylate kinase, apo form 4ake 110.7 376.1 486.8 478.2 Bovine Ribonuclease A 3rn3 80.5 145.1 225.6 235.0 Sperm Whale Myoglobin 1mbn 164.3 183.1 347.4 246.3 24 500 300 ζexp (10 -23 Erg-Sec) 400 200 100 0 0 100 200 av 300 av ζtotal = (ζDF + ζTR ) (10 -23 400 500 Erg-Sec) Figure 1: The combined friction from hydrodynamic and dielectric is plotted against the experimental results. The solid line shows the diagonal to guide the eye. 25 j=4 j=3 a+3d j=1 a j=2 a+d a+2d Bulk Figure 2: schematic diagram of the Molecular cavity and the hydration shell constituted by the bound water molecules. The bulk water molecules are more randomly oriented 26