EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING The Campy Training Kit

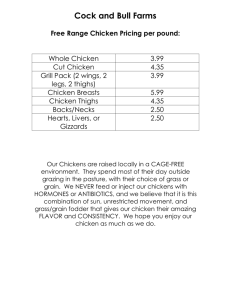

advertisement

EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING An Educational Intervention to Improve Raw Chicken Handling Practices in Restaurants: The Campy Training Kit Emmy S. Myszka, MPH, REHS1* 1 San Mateo County Environmental Health, 2000 Alameda de las Pulgas, Suite 100, San Mateo, California 94403 Key words: raw chicken, Campylobacter, training tools, active managerial control, intervention, food facilities, restaurants *Author for correspondence. Tel: (650) 372-6211; Fax: (650) 627-8244 Email: emyszka@smcgov.org 1 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Abstract Campylobacter species infections contribute to a large burden of foodborne illness infections and almost half are linked to food facilities. Campylobacter-contaminated poultry burdens public health as the most common pathogen-food combination. A case control study conducted by the County of San Mateo sought to measure the change in chicken handling practices following implementation of an educational invention with two delivery methods: the Campy Training Kit alone and supplemented by in-person training with the food facility manager. A repeated measures logistic regression model was used to analyze food safety before and after intervention. Both intervention groups showed increased use of thermometers to verify chicken cooking temperatures relative to a wait list control group. Furthermore, the two intervention groups did not differ from the wait list control group on other cross contamination risk factors, with the exception of the intervention-lite group having slightly better storage practices than the wait list control group. Additional research is needed to develop an intervention to prevent crosscontamination with raw chicken with ready-to-eat foods and food contact surfaces during preparation. 2 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Introduction Campylobacter spp. are microbes responsible for a large burden of acute bacterial gastroenteritis throughout the world. In the United States, the species is one of six key pathogens that contribute to over 50% of food-related illnesses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). Campylobacter spp. is frequently found in poultry and Campylobactercontaminated poultry is the most common pathogen-food combination burdening public health (Batz, Hoffman, & Morris, 2011). In 2012, an average of 14.2 cases of laboratory-confirmed Campylobacter species infections per 100,000 persons annually were reported in the United States (CDC, 2014). The incidence of campylobacteriosis in San Mateo County in 2012 was 35.2 per 100,000 persons, more than twice the national incidence (California Department of Public Health, 2015). These numbers clearly indicate that Campylobacter infections are a significant public health problem in San Mateo County. National surveillance data indicate that during 1998 through 2008, almost half (45%) of Campylobacter spp. foodborne illness outbreaks were linked with restaurants or delicatessens (CDC, 2013). These data suggest that food facilities are improperly handling and cooking poultry, the primary source of Campylobacter. Foodborne illness can be caused through crosscontamination from raw poultry to ready-to-eat (RTE) foods or the environment, such as food contact surfaces and equipment. Contaminated chicken can also cause foodborne illness when the chicken is not cooked to a temperature high enough to kill foodborne pathogens on or in the chicken. It is important to use a thermometer to check the internal temperature of meat, including chicken, because it is the only method to determine if meat is fully cooked (United States Department of Health & Human Services, 2015). 3 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified the top five risk factors responsible for foodborne illness outbreaks as: improper hot/cold holding temperatures of potentially hazardous food; improper cooking temperatures of food; contaminated utensils and equipment; poor employee health and hygiene; and food from unsafe sources (Bryan, 1988). Educational interventions for food facilities, therefore, should target these risk factors to protect the health and safety of consumers. Previous research has shown that educational interventions with food facilities are more effective when directed at owners/managers. Researchers at Iowa State University’s Department of Apparel, Educational Studies, and Hospitality Management found that “if the organizational culture is not supportive [of safe handling practices], then intervention at the individual level may not be sufficient.” They concluded that “the organization would benefit from providing the needed resources to practice food safety and instill values attached to food safety” (Abidin, Arendt & Strohbehn, 2011, p. 10). Since managers and owners have more direct influence over the organizational culture, targeting them is more likely to improve food safety practices than an educational intervention focused on food handlers. Research has also shown that training with an active, hands-on component leads to greater retention of the training concepts (Lillquist, McCabe, & Church, 2005). Specifically, train-the-trainer programs can provide subject matter experts (the food facility managers) with teaching skills in order to replicate a food safety program with food handlers. Through train-thetrainer programs, managers can increase their knowledge of food safety and learn how to teach others (Centers for Public Health Preparedness, 2005). Train-the-trainer models have been found successful in implementing public health preparedness programs (Orfaly et al., 2005). 4 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING In an effort to reduce campylobacteriosis in San Mateo County, San Mateo County Environmental Health Services Division (SMC EH) developed a targeted educational intervention for managers and food handlers for improving raw chicken handling practices in food facilities. Specifically, we developed a “Campy Training Kit” that included materials focused on safe storage, preparation, and cooking of raw chicken. Methods We provided the Campy Training Kit in two different delivery methods to groups of food facilities in San Mateo County. We assessed raw chicken handling practices in these facilities before and after implementation of the Campy Kit training. We measured the effectiveness of the training kit, as well as the two delivery methods, by comparing observed chicken handling practices in the two groups before and after the intervention as compared to a third group of food facilities that did not get the training. We hypothesized that the Campy Training Kit delivered with a train-the-trainer component (intervention-full: delivery of kit with an in-person training) would improve raw chicken handling practices over the Campy Training Kit by itself (intervention-lite: delivery of kit alone) and a wait list control group (receipt of training kit after the study was completed). Study Facilities. In 2011, San Mateo County (SMC) Environmental Health administered a pilot survey to all food facilities in the county that handled raw chicken. A total of 1,276 surveys were collected. A power analysis indicated that 700 facilities would be needed to detect a small to medium effect size (Cohen’s d≥.2) for an educational intervention. Thus, 700 facilities were selected from the food facility population in San Mateo County using a stratified, fixed allocation model, with simple random sampling within strata. The sampling was stratified by 5 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING language. More specifically, the initial pilot survey found that the three primary languages spoken in food facilities in San Mateo County were English (32.7%), Spanish (39.9%) and Chinese (17.9%: Cantonese 75.9% and Mandarin 24.1%). Thus, we stratified the sample such that in 40% of the facilities, the primary language spoken amongst all food handlers was English, in 40% of the facilities, the primary language spoke was Spanish, and in 20% of the facilities, the primary language spoke was Chinese. Study Groups and Procedure. From the 700 facilities selected for the study, 200 facilities were randomly assigned to a wait list control group (a group that would receive the intervention at the completion of the study), 250 were assigned to an intervention-full group (a group that received the training kit and an in-person training session with the manager), and 250 to the intervention-lite group (group that received the training kit alone). Facilities that cooked raw chicken directly from the frozen state were excluded from the study because the risk of cross-contamination in that procedure is minimal. In SMC EH, the food facilities are divided into inventories in 14 districts. Each district is assigned to an Environmental Health Specialist (EHS) who is responsible for routine inspections, re-inspections, and complaint investigations. Fourteen EHS collected the data for facilities in their districts and are herein called ‘data collectors.’ Data collectors were blind to the intervention condition of the facility. All 14 data collectors received training on how to administer the study measures that were used to observe chicken handling practices in the facility. Data collectors were required to attend two days of classroom standardization training and one day of field standardization training to ensure consistency in data collection. For the classroom training, SMC contracted with Vicky Everly, an EHS with extensive experience developing and implementing 6 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING standardization programs. The study measures were reviewed in detail and various scenarios were discussed to ensure data collectors would feel confident completing the measure in the facilities. Following classroom standardization training, all data collectors (14/14, 100%) participated in field standardization training with an EHS Food Specialist or Food Program Supervisor. The Food and Drug Administration’s Procedures for Standardization of Retail Food Safety Inspection Officers was used as a model for the field standardization, specifically Standard 2: Trained Regulatory Staff. A modified version of the Conference for Food Protection’s Field Training Worksheet was created to assess the performance elements and competencies necessary for the data collectors to collect the data independently. The trainer and the data collector completed side-by-side surveys and compared their results. Data collectors began collecting data independently once their survey and their EHS trainer’s survey were in 90% agreement at two facilities. Data collectors completed the assessments in their regularly assigned districts. Data collection replaced routine inspection for the facilities to reduce the burden of inspection time and encourage participation in the study. Only two facilities declined participation due to scheduling conflicts; two other facilities were subsequently added. Intervention. The “Campy Training Kit” was the primary intervention. The kit was developed by SMC EH and designed by Kuleana Design. Development of the materials for the Campy Training Kit were discussed in one-on-one discussions with 14 food facility managers and owners who provided feedback on what types of materials would be most useful in their kitchens. These facilities were later excluded from the study population. The Campy Training Kit consisted of a Raw Chicken Handling Training Manual for Owners and Managers, quick 7 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING reference cards, a video, a poster, and thermometer as well as refrigerator shelving labels. The materials were produced in English, Spanish, and Chinese. The written Chinese language can be understood by both Cantonese- and Mandarin-speakers. Campy Training Kits were hand-delivered to each facility in the two intervention study groups by an ‘EHS trainer,’ not the EHS data collector. In the intervention-lite group, the EHS trainer made sure the owner/operator received the kit. In the intervention-full group, there was an additional training component: the EHS trainer provided an individual training session to the manager. Six EHS trainers delivered the intervention-full: three delivered the training in English, two in Spanish and one in Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin). The purpose of the training was to “train-the-trainer” by having an EHS trainer instruct the manager on how to train food handlers on safe chicken handling using the training manual and other materials in the Campy Training Kit. The script for the in-person training component focused on the same basic principles that are present in the training manual: safe handling of raw chicken in storage, preparation, and cooking. The training was approximately 45 minutes long and was presented at a time convenient for the manager/owner. The Campy Training Kits were mailed to the facilities in the wait list control group upon completion of the study. Measures. Two surveys were developed for the study. The surveys were modeled after CDC Environmental Health Specialists Network’s (EHS-Net) Chicken Handling Study Protocol (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). The first survey, the Facility Assessment Survey, captured environmental observations made by the data collector. This survey utilized a binary (yes/no) response format to capture observations made about chicken storage, preparation and cooking. Each data collector was also asked to observe the presence or absence of training manuals, educational materials (e.g., posters, labels, checklists, and probe thermometers). For the 8 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING second round of Facility Assessment Surveys following implementation of the intervention, data collectors were also asked about the presence or absence of materials specific to the Campy Training Kit. The second survey, the Food Handlers Survey, was a food handler interview conducted by the data collector. Interview questions covered problems with training, management support, and knowledge of food handling practices. The interview used a force-choice response format. Data Analyses. Both the observation and the interview provided skip patterns for inapplicable questions and allowed for item non-response as a function of an inability to observe the behavior and/or the equipment in question. For some questions, the data collected did not enough variability in their distribution to provide sufficient numbers in the response levels for a stable statistical analysis. Due to the skip patterns, each facility’s survey would potentially have different numbers of applicable questions so using a count of ‘yes’ responses would not take into account the different number of total responses on the survey. To improve the stability of the analysis and ability to interpret the results, some survey questions were combined to generate new ‘domains’ to determine if the behaviors observed would increase the likelihood of Campylobacter spread. The domains that were constructed by combining survey questions are shown in Table 1. Specific questions composing each domain can be obtained from the author. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that two targeted educational interventions (full and lite) would improve chicken handling practices in comparison to a wait list control group. Since the answers to the survey questions were binary (yes/no responses), a repeated measures logistic regression model was used for this analysis. This regression model included terms to account for differences between the groups at pre-assessment on the defined outcomes and to account for the change over time between pre- 9 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING and post-assessment. An interaction term between the three study groups group and the time variable (pre vs. post) yielded the point estimates and confidence intervals for the assessment of the intervention effects. All models used the wait list control group and pre-assessment as the referent categories. As long as a facility had one data point for an outcome, it was retained in the model (just pre-assessment or just post-assessment). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented for each study group comparison against the wait list control group for each outcome. Implementation of the intervention in the lite and full interventions was examined descriptively. More specifically, we examined the presence/absence of Campy materials in facilities provided with the lite or full intervention as compared to the wait list control group. Results Of the facilities included in this study, 15.9% were chains with 20 or more locations in the United States while 83.0% were independent. In 26.3% of the facilities, the average amount of chicken purchased weekly was less than 50 pounds, 19.0% of the facilities purchased 50-99 pounds of chicken weekly and 51.8% of the facilities purchased 100 pounds or more chicken weekly. In 80.5% of the facilities, up to 50% of the meals served included chicken while 17.9% of the facilities include chicken in over 50% of the meals served. Of the food facility managers, 86.2% had ever held food safety certification, while 77.1% of those managers held a current food safety certification. Furthermore, 87% of respondents indicated that “all” or “most” of the food handlers working their shift had valid food handler cards. Facility Assessment by Intervention Group. Three surveys from the intervention-full group, one record from the intervention-lite group and one record from the wait list control group 10 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING had to be removed from analyses because they were incomplete. Table 2 presents the results of the Facility Assessment Surveys by intervention group. Overall, practices changed for all three groups. Both the intervention-lite group and the intervention-full group showed a statistically significant increase in thermometer use when compared to the wait list control group. In addition, the intervention-lite group evidenced a statistically significant greater reduction in problems with storage practices as compared to the wait list control group. Problems with storage practices included storing chicken above ready-to-eat or cooked foods or above other raw protein with lower cooking temperatures or storing raw chicken without a cover or in a leakproof container. No statistically significant differences were observed in cross-contamination in storage or thawing, thawing practices, preparation practices, sanitizing food contact surfaces and equipment, wiping cloth practices, or cross-contamination during cooking. Food Handler Outcomes by Intervention Group. On the Food Handler Survey, there was a statistically significant reduction in problems associated with training on safe handling practices among those in the intervention-lite group compared to the wait list control group (Table 3). Problems with training could include a manager failing to explain why the food handler needed to do training on how to prepare raw chicken safely, the food handler failing to understand the information given by the manager, or the food handler not learning new information or not feeling more confident in his/her ability to prepare chicken safely. Table 3 also shows a reduction in problems with training in the intervention-full group, but it was not statistically significant. The level of support was measured by asking how often the food handler has enough support from the manager and if the food handler has enough time and proper equipment to prepare food safely. On each of the questions, the food handlers reported a high level of support so the overall ‘support’ domain was also high. Each group had an almost 11 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING uniform endorsement of ‘always’ being supported at pre and post assessment. There were no significant differences between the intervention groups and the wait list control group. Finally, there were modest increases in knowledge about safe chicken handling in all three study groups; neither of the intervention groups had increases that surpassed those evidenced by the wait list control group. Results for support and knowledge are presented in Table 4. Intervention Fidelity. Given that all three groups evidenced improvement on the outcome measures between the pre- and post-assessments and there appeared to be no/little differential effect due to the intervention(s), examination of fidelity to the intervention was warranted. Intervention fidelity was examined in two ways: 1) observation of “Campy” training materials by intervention group and; 2) utilization of “Campy” materials for training by intervention group. As reflected in Table 5, of all the materials included in the Campy Kit, the training manual, educational posters, and thermometers were the most frequently observed materials at intervention facilities. The training manual was observed in 9.97% of the intervention-full and 9.13% of the intervention-lite facilities; the posters were observed in 21.36% of the interventionfull and 20.45% of the intervention-lite facilities; and the thermometer was observed in 19.05% of the intervention-full and 17.90% of the intervention-lite facilities. It is worth noting that studyprovided materials were observed in very few facilities in the wait list control group. This suggests that cross-over between the intervention groups and the wait list control group was low. Despite receiving the materials, we found that only 54% of facilities in the intervention-full group and 45% of facilities in the intervention-lite group reported having used the “Campy” materials for training. 12 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Discussion Although some food handling practices to prevent Campylobacter-contaminated poultry improved over time, the Campy Training Kit did not significantly improve raw chicken handling practices, even when supplemented by a 45-minute in-person, train-the-trainer educational component. Overall, the full and the lite interventions were not significantly better than the wait list control group on observational measures of food handling practices with exception of thermometer use. Similarly, food handlers provided with either the full or lite intervention did not report significantly more knowledge of Campylobacter or increased support from management than the wait list control group. Both the full and the lite interventions were significantly better than the wait list control group in increasing thermometer use to verify chicken cooking temperatures. This is a noteworthy exception to the overall finding of non-significance because obtaining the proper cooking temperature is an important prevention measure for campylobacteriosis. It would appear that distribution of the Campy Kits is all that is needed to improve thermometer use; the inperson training component did not provide additional benefit. The same finding holds true for the other materials in the Campy Kit. Although the Campy Kit was distributed to all the facilities receiving the full or lite intervention, utilization of the Campy materials was at most 51% in both intervention groups. In other words, the in-person training did not result in greater use of the Campy materials. The results of the present study may be impacted by the Hawthorne effect (aka observer effect). Recall that data collectors replaced their routine inspection procedures with a new format that allowed them to administer the study surveys. This change was not hidden from the facility managers and food handlers. In fact, data collectors informed operators that the visit was part of 13 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING a special project about raw chicken and there was little doubt that they were being observed with specific reference to their chicken handling practices. Unlike a routine inspection, which would assess health and hygiene practices throughout the food facility, data collectors focused only on raw chicken storage, preparation, and cooking. It has been well established that being observed or monitored can increase behavior in a positive direction (Campbell, Maxey & Watson, 1995). In addition to the Hawthorne effect, it is important to point out that the current study was conducted at the same time as policy changes were enacted for food handlers which may have increased knowledge of food safety. For example, 87% of respondents indicated that “all” or “most” of the food handlers working their shift had valid food handler cards. Beginning July 1, 2011, food handlers were required to obtain a food handler card by taking a training course from a recognized provider that provides basic, introductory food safety instruction as specified in the California Retail Food Code Section 113948. The Hawthorne effect, coupled with changes in food handler requirements, may explain high pre-assessment values and the observed improvement in the wait list control group. Study strengths include blind data collectors, standardization training provided to data collectors, observational data (in addition measures reported by food handlers in interviews) and large data set. Study limitations include binary yes/no responses and forced multiple choice responses on the interview that may not capture more subtle information, missing/incomplete data, and the possibility of different data collectors at pre and post assessment (which may add more variability despite standardization training). 14 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Conclusion We hypothesized that the Campy Training Kit delivered with a train-the-trainer component (intervention-full) would improve raw chicken handling practices over the Campy Training Kit by itself (intervention-lite) and a wait listed control group. While the interventionfull was not found to be more effective than the intervention-lite group or the wait list control group, the Campy Kit was found to increase thermometer use to verify chicken cooking temperatures. Considering that prevention of cross-contamination of raw chicken juice with ready-to-eat foods and food contact surfaces is also an important prevention measure for campylobacteriosis, more research is needed to develop training materials to minimize these risk factors. Acknowledgements This publication is based on research funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Environmental Health Specialists Network (EHS-Net), which is supported by a CDC grant award funded under CDC-RFA-EH05-013. San Mateo County acknowledges the Registered Environmental Health Specialists who collected data. Special acknowledgement also goes to Brenda Le and Laura Brown, PhD for their contributions to the study. Special thanks goes to Vicki Everly for conducting the trainings and Prins, Williams Analytics, LLC for providing support with data processing and analysis. 15 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING References Abidin, U.F., Arendt, S.W., & Strohbehn, C.H. (2011). Proceedings from International Council on Hotel, Restaurant, and Institutional Education Annual Conference: An Exploratory Investigation on the Role of Organizational Influencers in Motivating Employees to Follow Safe Food Handling Practices. Batz, M.B., Hoffman, S., & Morris, J.G. Jr. (2011). Ranking the risks: the 10 pathogen-food combinations with the greatest burden on public health. University of Florida, Emerging Pathogens Institute. Retrieved from http://www.epi.ufl.edu/?q=rankingtherisks Bryan, F.L. (1988). Risks of practices, procedures, and processes that lead to outbreaks of foodborne diseases. Journal of Food Protection, 51, 498–508. Campbell, J.P., Maxey, V.A., & Watson, W.A. (1995). Hawthorne effect: implications for prehospital research. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 26(5), 590-4. California Department of Public Health. (2015). Yearly summaries of selected general communicable diseases in California, 2011-2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdph.ca.gov/data/statistics/Documents/YearlySummaryReportsofSelectedGe neralCommDiseasesinCA2011-2014.pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). EHS-Net Chicken Handling Study Protocol. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/ehs/EHSNet/Study_Tools/EHS-Net-ChickenHandling-Study.pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Vital Signs: Incidence and Trends of Infection with Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food – Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 1996—2010. Morbidity and Mortality 16 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Weekly Report, 60, (22); 749-755.Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6022a5.htm Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Surveillance for Foodborne Disease Outbreaks – United States, 1998-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(2). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6202.pdf Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network: FoodNet surveillance report for 2012 (Final Report). Atlanta, Georgia: United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Public Health Preparedness. (2005). Train the trainer: Survey of CPHP resources. Retrieved from http://preparedness.asph.org/perlc/documents/TrainTheTrainer.pdf County of San Mateo Health System. (2012-2014). Communicable Diseases Quarterly Reports, (19-30). Retrieved from http://www.smchealth.org/alerts#Communicable%20Disease%20Quarterly%20Reports Lillquist, D.R., McCabe, M.L, & Church, K.H. (2005). A comparison of traditional handwashing training with active handwashing training in the food handler industry. Journal of Environmental Health, 67(6), 13-16. Orfaly, R.A., Frances, J.C., Campbell, P., Whitmore, B., Joly, B., & Koh, H. (2005). Train-thetrainer as an educational model in public health preparedness. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 11(6), 123-127. United States Department of Health & Human Services. (n.d., updated August 25, 2015). Safe minimum cooking temperatures. Retrieved from http://www.foodsafety.gov/keep/charts/mintemp.html 17 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Table 1. Domains constructed from composites of survey questions Facility Assessment Survey Food Handler Survey Cross-contamination in storage or thawing Problems with training Problems with storage practices Support Problems with thawing practices Knowledge Good preparation practices Problems with sanitizing equipment Good Wiping Cloth practices Thermometer used Chicken undercooked Cross-contamination during cooking 18 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Table 2. Distribution of facility outcomes, by intervention group and time, and odds ratios from population-averaged logistic regression model Pre Post Outcome and group Category n (%) n (%) OR 95% CI Cross-contamination in storage or thawing Full Yes 35 (14.2) 18 (7.5) 0.87 0.41, 1.83 No 191 (77.3) 198 (82.5) Missing 21 (8.5) 24 (10.0) Lite Yes 34 (13.7) 23 (9.6) 1.21 0.59, 2.49 No 196 (78.7) 192 (81.4) Missing 19 (7.6) 21 (8.9) Control Yes 38 (19.1) 24 (12.5) Ref. No 138 (69.6) 157 (81.8) Missing 23 (11.6) 11 (5.7) Problems with storage practices Full Yes 122 (49.4) 83 (34.6) 0.84 0.53, 1.33 No 108 (43.7) 141 (58.8) Missing 17 (6.9) 16 (6.7) Lite Yes 140 (56.2) 76 (32.2) 0.35, 0.89 0.56* No 93 (37.4) 145 (61.4) Missing 16 (6.4) 15 (6.4) Control Yes 94 (47.2) 74 (38.5) Ref. No 87 (43.7) 111 (57.8) Missing 18 (9.1) 7 (3.7) Problems with thawing practices Full Yes 14 (5.7) 7 (3.0) 0.69 0.20, 2.36 No 230 (93.5) 225 (94.9) Missing 2 (0.8) 5 (2.1) Lite Yes 12 (4.8) 8 (3.4) 0.93 0.27, 3.19 No 230 (92.7) 222 (94.9) Missing 6 (2.4) 4 (1.7) Control Yes 12 (6.0) 9 (4.7) Ref. No 182 (91.5) 181 (94.3) Missing 5 (2.5) 2 (1.0) 19 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Table 2 (cont). Distribution of facility outcomes, by intervention group and time, and odds ratios from population-averaged logistic regression model Pre Post Outcome and group Category n (%) n (%) OR 95% CI Good preparation practices Full Yes 31 (12.6) 62 (25.8) 1.43 0.73, 2.80 No 174 (70.5) 142 (59.2) Missing 42 (17.0) 36 (15.0) Lite Yes 28 (11.2) 46 (19.5) 1.19 0.59, 2.37 No 187 (75.1) 148 (62.7) Missing 34 (13.7) 42 (17.8) Control Yes 27 (13.6) 42 (21.9) Ref. No 142 (71.4) 129 (67.2) Missing 30 (15.1) 21 (10.9) Problems with sanitizing equipment Full Yes 40 (16.2) 30 (12.5) 1.18 0.60, 2.31 No 175 (70.9) 174 (72.5) Missing 32 (13.0) 36 (15.0) Lite Yes 45 (18.1) 26 (11.0) 0.85 0.43, 1.69 No 177 (71.l) 182 (77.1) Missing 27 (10.8) 28 (11.9) Control Yes 43 (21.6) 28 (14.6) Ref. No 133 (66.8) 135 (70.3) Missing 23 (11.6) 29 (15.1) Good wiping cloth practices Full Yes 76 (30.77) 115 (47.92) 1.19 0.69, 2.05 No 131 (53.04) 90 (37.50) Missing 40 (16.19) 35 (14.58) Lite Yes 85 (34.54) 87 (36.86) 0.72 0.42, 1.24 No 132 (53.01) 100 (42.37) Missing 31 (12.45) 49 (20.76) Control Yes 58 (29.15) 75 (39.06) Ref. No 116 (58.29) 81 (42.19) Missing 25 (12.56) 36 (18.75) 20 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Table 2 (cont). Distribution of facility outcomes, by intervention group and time, and odds ratios from population-averaged logistic regression model Pre Post Outcome and group Category n (%) n (%) OR 95% CI Cook uses thermometer to check temperature Full Yes 34 (13.77) 63 (26.25) 1.35, 3.93 2.30* No 195 (78.95) 158 (65.83) Missing 18 (7.29) 19 (7.92) Lite Yes 46 (18.47) 72 (30.51) 1.19, 3.34 2.00* No 185 (74.30) 148 (62.71) Missing 18 (7.23) 16 (6.78) Control Yes 42 (21.11) 42 (21.88) Ref. No 138 (69.35) 140 (72.92) Missing 19 (9.55) 10 (5.21) Chicken undercooked when tested Full Yes 23 (9.31) 8 (3.33) 0.35 0.11, 1.07 No 210 (85.02) 212 (88.33) Missing 14 (5.67) 20 (8.33) Lite Yes 27 (10.84) 15 (6.36) 0.66 0.25, 1.78 No 208 (83.53) 201 (85.17) Missing 14 (5.62) 20 (8.47) Control Yes 14 (7.04) 12 (6.25) Ref. No 170 (85.43) 168 (87.50) Missing 15 (7.54) 12 (6.25) Cross-contamination during cooking Full Yes 129 (52.23) 79 (32.92) 0.79 0.49, 1.26 No 109 (44.13) 149 (62.08) Missing 9 (3.64) 12 (5.00) Lite Yes 132 (53.01) 85 (36.02) 0.88 0.55, 1.41 No 109 (43.78) 138 (58.47) Missing 8 (3.21) 13 (5.51) Control Yes 105 (52.76) 78 (40.63) Ref. No 83 (41.71) 104 (54.71) Missing 11 (5.53) 10 (5.21) 21 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Table 3. Distribution of food handler survey outcomes, by intervention group and time, and odds ratios from population-averaged logistic regression model (excluding managers and owners) Pre Post Outcome and group Category n (%) n (%) OR 95% CI Problem with training on safe handling practices Full Yes 24 (16.78) 14 (10.85) 0.65 0.26, 1.63 No 101 (70.63) 101 (78.29) Missing 18 (12.59) 14 (10.85) Lite Yes 27 (18.37) 7 (5.79) 0.10, 0.84 0.30* No 106 (72.11) 100 (82.64) Missing 14 (9.52) 14 (11.57) Control Yes 28 (21.71) 22 (20.18) Ref. No 85 (65.89) 75 (68.81) Missing 16 (12.40) 12 (11.01) 22 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Table 4. Distribution of continuous food handler survey outcomes, by intervention group and time, and differences from a linear mixed effects regression model (excluding managers and owners) Pre Post Outcome and group n M (SD) n M (SD) b 95% CI Support Full 133 11.42 (1.12) 114 11.45 (1.11) -0.26 -0.62, 0.10 Lite 139 11.50 (0.91) 108 11.51 (0.95) -0.28 -0.64, 0.08 Control 116 11.19 (1.29) 94 11.48 (0.85) Ref. Knowledge Full 143 4.26 (1.24) 129 4.97 (1.16) 0.13 -0.25, 0.52 Lite 147 4.41 (1.25) 121 4.81 (1.35) -0.13 -0.52, 0.26 Control 129 4.19 (1.43) 109 4.73 (1.49) Ref. 23 EDUCATIONAL INTERVENTION TO IMPROVE RAW CHICKEN HANDLING Table 5. Utilization of materials identified in facilities by intervention group Full (n=237) Lite (n=234) Control (n=192) N (%) N (%) N (%) “Campy” materials (Post) Manuals/SOP 23.63 (9.97) 21.37 (9.13) 1.04 (0.54) Shelf labeled 9.70 (4.09) 11.11 (4.75) 0.52 (0.27) Educational posters 50.63 (21.36) 47.86 (20.45) 1.56 (0.81) Checklists 5.06 (2.14) 4.27 (1.82) 0.00 (0.00) Thermometer 45.15 (19.05) 41.88 (17.90) 2.08 (1.08) 24