Water Resource Management in Northeast Ohio: Opportunities for Environmental Protection

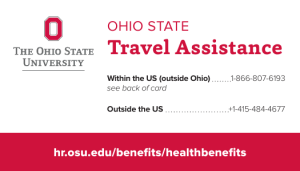

advertisement