LAWYERS TO THE FINANCIAL

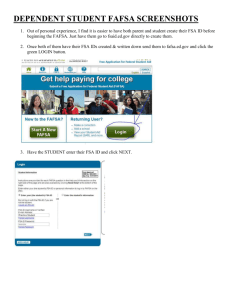

SERVICES INDUSTRY

www.klng.com

Winter 2005

Take Stock

Alternative investment

products - the US approach

to regulation

Introduction

Until recently, alternative investment

products such as hedge funds that were

offered into the United States were

invariably structured so as to qualify for

exemptions from registration under the

US Investment Company Act of 1940

(the "1940 Act") and the US Securities

Act of 1933 (the "1933 Act"). Most still

do, and these exemptions substantially

dictate how these products can be

marketed in the United States. More

recently, certain alternative investment

products have been registered either

under the 1933 Act, the 1940 Act or

both. Registration under these statutes

can dramatically enhance distribution

options.

1933 Act limitations on

marketing

Within the United States, hedge funds

and other alternative investment

products are typically structured as

limited partnerships or limited liability

companies. The fund sponsor sells

interests in the fund in order to raise the

money that is invested in portfolio

securities or commodities in accordance

with the fund’s investment strategy.

The limited partnership or limited

liability company interests that the

sponsor sells are themselves securities.

To sell these interests, the sponsor

must comply with US federal and state

law applicable to the offer and sale of

securities. Most sponsors choose to

offer the interests pursuant to an

exemption from registration under the

1933 Act. While there are numerous

exemptions available under the 1933

Act, hedge fund sponsors rely

exclusively on the exemption in Section

4(2) of the 1933 Act. Section 4(2)

exempts from the registration

requirements of the 1933 Act

"transactions by an issuer not involving

any public offering". An offering that is

not public is generally called a private

offering, and the Section 4(2)

exemption is referred to as the private

placement exemption.

The choice of exemption under the

1933 Act is dictated by the

requirements for an exception under

the 1940 Act. The 1940 Act regulates

entities that are in the business of

investing in the securities of other

companies. A fund that invests in

securities, such as a typical hedge fund,

must either register as an investment

company under the 1940 Act or seek an

exception from the definition of

"investment company". Funds

Welcome to the Winter Edition.

We provide an integrated

international service for our financial

services industry clients. Many

readers will have attended our

successful joint US/UK seminars on

financial services topics, and this

edition of Take Stock starts with an

article penned by one of the leaders

of our hedge fund practice in the US.

Contents

Alternative investment products the US approach to regulation

1

General Insurance Regulation

4

Transaction Reporting Issues

5

Commission urges action on

clearing and settlement systems

6

The e-money directive an update

7

Financial products and

misrepresentation - the risks

8

Proposed changes to the

Consumer Credit Act

9

New company reporting

regulations from the DTI

10

D & O Insurance Cover - a few

myths and realities

11

MiFID and the FSA’s discussion

11

paper on bond market transparency

The Shell Reserves Affair

12

Who to contact

12

Take Stock

organised in the United States typically

rely on the Section 3(c)(1) or Section

3(c)(7) exception under the 1940 Act.

A fund that meets all of the

requirements of either of these sections

will be deemed not to be an investment

company for purposes of the 1940 Act

and will, therefore, not be required to

register under the 1940 Act. A

requirement of each of these sections is

that the fund not be making and not

currently propose to make a public

offering of securities. The fund must

therefore make private offerings of its

securities under Section 4(2) of the 1933

Act.

An offshore fund may make offers and

sales of its securities in the United

States or to US persons outside the

United States, but only in accordance

with the Section 3(c)(1) or Section

3(c)(7) exception under the 1940 Act.

Thus, to the extent that an offshore

fund sells its interests in the United

States or to US persons, it must do so in

accordance with all of the requirements

of the private placement exemption.

A failure by a fund to meet all of the

requirements for the private placement

exemption can give rise to a right of

rescission on the part of the investor,

meaning that the investor can demand a

return of its purchase price plus

statutory interest. An investor is of

course most likely to exercise such a

right if the fund has lost money. If the

fund no longer has sufficient assets to

meet rescission claims, the fund

sponsors may be exposed to personal

liability. Moreover, if investors

challenge the availability of the private

placement exemption in an attempt to

establish a right of rescission, the

burden of proving the availability of the

exemption is on the fund that is

claiming the exemption.

1940 Act limitations on

marketing

A fund that relies on the Section 3(c)(1)

or the Section 3(c)(7) exception under

the 1940 Act is not only limited to

offering its interests in private offerings.

Each of these exceptions imposes

additional requirements that limit a

fund’s ability to market its interests.

The Section 3(c)(1) exception limits the

number of beneficial owners in the

fund to 100. The sponsor of such a

fund will usually impose a high

minimum investment amount (typically

US$1 million) so that the fund will have

sufficient assets under management

even with just 100 investors. The

Section 3(c)(7) exception requires that

all investors in the fund be so-called

"qualified purchasers" at the time of

sale, a relatively high standard that

includes individuals with at least US$5

million in investments (as defined by

rule) and companies with at least US$25

million in investments.

New products

If a fund and its manager rely on the

exemptions described above, they will

be subject to multiple overlapping

restrictions on marketing. Some fund

sponsors have developed new products

that do not rely on one or more of these

exemptions to enhance their ability to

market the interests in their funds.

Two of these new products are

described on page 3.

2

WINTER 2005

www.klng.com

Registered funds of hedge

funds

A registered fund of hedge funds is

registered under the 1940 Act as a

closed-end investment company. It

invests in hedge funds that are

excepted from the definition of

investment company under the 1940

Act.

The shares in the fund may be

registered for sale under the 1933 Act,

in which case sales can be made without

regard to the prohibition against general

solicitation and general advertising.

Even if the shares are registered for sale

under the 1933 Act, however, as a

condition to declaring effective the

registration statements of such funds,

the SEC has frequently required that

the shares be sold only to accredited

investors. This requirement does not

derive from the private placement

exemption because the offering is

registered under the 1933 Act. The

SEC staff are apparently imposing the

accredited investor standard in an

attempt to assure that funds of hedge

funds will be marketed only to investors

that are capable of understanding their

relatively complex structures. The

SEC staff have also sometimes imposed

a minimum offering amount (usually

US$25,000), presumably for the same

reason.

Because the fund is registered under

the 1940 Act, sales are not limited to

qualified purchasers, nor is there a limit

on the number of investors in the fund.

Long-short mutual funds

A significant change in the US Internal

Revenue Code in 1997 paved the way

for a new breed of mutual fund that can

invest both long and short. Prior to this

change, if an investment company

derived 30 per cent or more of its gross

income from securities held for less

than three months, it would not qualify

for pass-through tax treatment under

Subchapter M of the Internal Revenue

Code. Failure to qualify for passthrough tax treatment would mean that

the investment company would be

taxed as a corporation, which would

result in taxation at both the fund and

investor levels - a very undesirable

result. Securities sold short were always

considered to be held for less than three

months, because they were sold

immediately. Few investment

companies even attempted to operate

within the confines of this so-called

"short-short" rule.

Congress amended the Internal

Revenue Code in 1997 to eliminate the

short-short rule. This has led to the

creation of numerous 1940 Act registered funds that can offer many

strategies of the sort used by hedge

funds. Such funds sell their shares

publicly to an unlimited number of

investors in minimum amounts as low

as US$500. Sales are not limited to

qualified clients if there is no

performance-based fee to the adviser, or

if the performance-based fee is a

fulcrum fee (a fee that is based on the

net asset value of the fund that

increases or decreases proportionately

with the performance of the fund

relative to an appropriate index).

Through the use of new products such

as these, hedge fund strategies are

being made available to larger numbers

of investors. They are also being made

available to investors who may not have

been able to invest directly in hedge

funds, either because they are not able

to invest the high minimum investment

amount typically required of hedge

fund investors or because they are not

accredited investors.

For further advice on hedge funds and

alternative investment products in the

US please contact Nicholas S. Hodge by

email at nhodge@klng.com or by

telephone on +1 617 261 3210.

WINTER 2005

3

Take Stock

General insurance regulation

FSA review

On 23 September 2005 the FSA

announced that it intends to review its

general insurance regulatory regime.

This review will take place alongside its

review of the mortgage regime, which

was announced earlier this year.

Although the general insurance

regulatory regime only began in January

2005, the FSA wants to assess whether

the regime is actually meeting its

objectives.

The FSA has announced that the

mortgage regime review will commence

in December 2005 and the general

insurance regime review will commence

in April 2006. These reviews are

intended as preliminary fact-finding

exercises and depending upon the

results the FSA may decide to consult

on changes in the usual way, although

any changes that the FSA are able to

make will be restricted by the

requirements of the EU's Distance

Marketing Directive and Insurance

Mediation Directive.

Virtually every adult in the UK has

some involvement with general

insurance. In 2004 some 35 million UK

consumers took out or renewed 77

million policies for contents, vehicle,

medical, payment protection and other

types of general insurance with

premiums totalling £28.5 billion. With

so many members of the public

involved, and with over 10,000

authorised brokers active in the general

insurance industry, it is a substantial

area that the FSA is keen to ensure is

efficiently regulated.

4

WINTER 2005

The review will have three principal

features:

Encouraging feedback from firms

that are regulated for general

insurance activities on what they

believe is good or bad about the

existing regime and which areas of

the regime would benefit from

greater analysis and re-examination;

Undertaking consumer research to

assess whether the supposed benefits

of the regime have any real effect;

and

Assessing whether or to what extent

the general insurance industry is

actually complying with the regime.

Payment protection

insurance

The sale of insurance policies to cover

an insured person's obligation to make

mortgage, credit card or loan payments

when they are unable to as a result of

illness or redundancy, known as

payment protection insurance or "PPI"

has been the subject of much press

criticism over recent years. The FSA,

now that it has a regulatory structure in

place for general insurance, is keen to

tackle poor or aggressive sales practices,

unsuitable products, small print and

complex terms. It is also looking to

tackle the risks to consumers which

arise as a result of the sale of PPI on the

back of other transactions. In

connection with its proposed general

insurance review the FSA has, by

conducting a 'mystery shopping'

exercise, been assessing how firms sell

PPI linked to other financial products.

The FSA has been determined to

improve standards in this area. On 4

November 2005 the FSA published the

results of its exercise in the form of

examples of good and bad practice,

setting out what it expects of firms. The

FSA prefers to see the industry find its

own solution to the mis-selling of PPI

by improving its own standards; the

alternative, which is currently only

starting to be considered by the FSA, is

that the FSA may introduce more

stringent disclosure requirements, and

potentially may even require that the

sale of PPI be unbundled from the

primary transaction altogether.

www.klng.com

Transaction reporting issues

Transaction reporting has been a hot

topic in the financial press over the past

few months, and is set to remain a

popular discussion topic over the

coming months.

New transaction reporting

system

Earlier this year the FSA asked several

firms to test the FSA's new transaction

reporting system, known as 'TRS'. The

FSA has said that the tests were

successful and the full system will go

live during November 2005. All firms

who currently use the existing Direct

Reporting System ("DRS") will have to

migrate to the TRS before April 2006.

At an as yet undecided date in 2006 the

FSA will switch off DRS, so it is

fundamental that all firms migrate to

TRS.

The migration to TRS should be

simple and efficient for all firms since it

does not require that any software be

installed as it is web-based, and the

feedback from the FSA should be

immediate, so firms will know if they

have submitted their information

correctly. For further advice on the

change to TRS please see the FSA

website at the following link:

www.fsa.gov.uk/pages/doing/regulated/

returns/mtr/index.shtml

Penalty for breach of SUP

17 transaction reporting

rules

In August 2005 the FSA fined Bear

Stearns International Limited £40,000

for failing to report transactions in

contracts for differences ("CFDs") to

the FSA between August 2001 and

March 2005. This was the first ever fine

imposed by the FSA for failure to

report such transactions under Chapter

17.4 of the Supervision Handbook

("SUP").

SUP 17.4 requires authorised firms to

make transaction reports in respect of

all reportable transactions which they

make, either on their own account or on

behalf of another. Reportable

transactions are defined in SUP 17.5

and include transactions involving

CFDs on equities. (It does not include

contracts for differences where the

contract is based on the fluctuation in

the price or value of a basket of

equities, or on the value of a dividend

payment or payments on equities).

The FSA relies on authorised firms to

make accurate and complete

transaction reports. The FSA is

concerned that incomplete or

inaccurate transaction reporting by a

firm may hinder its ability to monitor

the market effectively and might

consequently have some impact on the

FSA's ability to maintain confidence in

the financial system and reduce

financial crime.

The FSA fined Bear Stearns even

though the failure to report was

inadvertent, it had provided all

outstanding transaction reports to the

FSA by the end of March 2005, and it

had implemented new systems and

controls to conduct regular reviews of

transaction reporting for existing and

prospective new products. Although

the FSA has not made its reasoning

explicit, it may be presumed that the

FSA sought to make an example of

Bear Stearns as a warning to other firms

who trade in CFDs. Transaction

reporting in reportable transactions is a

requirement of SUP, and with the new

TRS system there should be no

excuses for failing to report

transactions. The deadline for making

transaction reports is the end of the

business day after which the trade took

place.

Transaction reporting and

MiFID

MiFID - or the EU's Markets in

Financial Instruments Directive is

gathering pace as a pan-European

compliance blueprint which will

replace the existing Investment

Services Directive (see article in the

Summer 2005 issue of Take Stock). As

a fundamental and wide reaching piece

WINTER 2005

5

Take Stock

of European legislation it will have an

effect on many areas of the financial

services industry - from transparency in

the bond market (see article on page

11) to transaction reporting.

The FSA will be publishing a

consultation paper later this year on the

rule changes required to implement

MiFID in the UK, but in the interim

the FSA has set out the key areas of

transaction reporting that will be

affected by the implementation of

MiFID:

More transactions will have to be

reported as the definition of a

'reportable product' will be widened

to include certain interest rate and

commodity derivatives as well as

OTC derivatives.

More firms will be required to make

transaction reports as MiFID will

require that firms must make a

transaction report when their

transaction involves a financial

instrument admitted to trading on a

regulated market whether or not that

transaction takes place on a

regulated market.

EEA passported branches of a firm

will have to report to their host state

regulator.

It is likely that the content of a

transaction report will be increased,

although the additional information

that will have to be reported should

already be information available to

the reporting firm.

The FSA's consultation paper will

consider these and other issues when it

is published later this year.

6

WINTER 2005

Commission Urges action on

Clearing and Settlement

Systems

Clearing and settlement involves the

various procedural steps that take place

after securities have been traded so as

effectively to transfer the securities

from the seller to the buyer and the

cash from the buyer to the seller.

In August 2004 the European

Commission (the "Commission")

launched a consultation on the clearing

and settlement process which was

followed in June 2005 by a 160 page

report describing the securities trading,

clearing and settlement infrastructures

of the cash, equities and bonds markets

in the 25 member states of the EU (for

further comment on transparency in

the bond market please see page 11).

The Commission noted that while

there have been a number of mergers

of securities market infrastructures

which have reduced the fragmentation

of the clearing and settlement systems

market in Europe, the consolidation

process is far from complete and further

structural changes are likely.

Furthermore, in terms of regulation,

there is a considerable way to go before

there will be anything that could be

described as a single European market

for such systems. In practice, in most

member states, securities traders are

required to use a specific settlement

service provider with no option to use

alternative systems (e.g. those based in

other member states).

Without some degree of consistency in

clearing and settlement systems across

the EU, for example in terms of rights

www.klng.com

of access and choice, common

governance arrangements and common

regulation, there will be limited

competition between clearing and

settlement systems providers and a

material restriction on the degree to

which trading takes place across the

member states of the EU. These are

serious concerns that the Commission

is keen to address.

A legal working party was established

by the Commission in 2004 which met

for the first time in January of this year

to discuss the legal issues surrounding

the possible regulation of the clearing

and settlement systems in Europe.

If the Commission does decide that

action is required, it will draft a

directive setting out certain common

principles as a means to ensure

consistency of approach and regulation

across the EU. More conservative

voices are lobbying for a laissez faire

approach - arguing that if customer

demand is calling for a more integrated

approach then the market will itself

respond. Politically, there is also some

caution within the Commission to

introduce legislation unless there is a

general consensus in favour from the

member states.

Any legislation is likely to be some

years away, but lobbying will be ongoing from regulators, trade

associations and traders themselves

each of whom will need the

Commission to understand their

perspective. If you have a particular

interest in this area then please contact

Neil Baylis in our London office by

email at nbaylis@klng.com for any

further information.

Summary and update on the

e-money directive

In the three years since the EU's Emoney directive (the "Directive") was

implemented there have been some

substantial advances and changes in the

world of technology and finance. On 14

July 2005 the European Commission

(the "Commission") launched a review

of the Directive in which stakeholders

are invited to give the Commission

their views. The deadline for responses

on the public consultation expired on

14 October 2005.

The E-money directive came into force

on 27 April 2002, and was incorporated

into English law on that date by the

Electronic Money (Miscellaneous

Amendments) Regulations 2002. Emoney may be defined as 'monetary

value that is stored on an electronic

device (e.g. as a chip card or computer

memory) that is accepted by

undertakings other than the issuer and

is intended to make payments of a

limited amount'.

The objectives of the Directive were:

To protect the consumer by ensuring

the integrity and stability of Emoney institutions;

To improve the single market in

financial services;

To avoid distortion of competition

by subjecting both E-money and

traditional credit institutions to

supervision; and

To provide the legal framework

necessary for the development of ecommerce.

Issuing E-money is a regulated activity

under the Financial Services and

Markets Act 2000 ("FSMA") and the

FSA regulates E-money in a similar

way to its regulation of other financial

products.

The Directive allows the FSA to waive

the application of the Directive to

certain E-money issuers by issuing

"certificates". HM Treasury's thinking

behind the waiver is that by exempting

as many E-money issuers as possible

from the requirements of the Directive,

this should lead to increased

competition and the development of

the industry. The FSA is empowered

to grant certificates on a case-by-case

basis, provided that issuers meet

certain criteria relating to the amount of

E-money issued, and the way it is used.

Examples of E-money formats

benefiting from the waiver might

include an electronic travelcard or

smart cards used on a university

campus.

The Directive is under review.

Conceived at the height of the ecommerce boom, it was difficult to

foresee how the E-money industry

would evolve at the time it was drafted.

Advances in technology have spawned

new business models, such as mobile

telephone payments, and internet

payment facilities. The Commission

WINTER 2005

7

Take

StockChecks

Travellers’

wants to analyse whether the Directive

still fulfils its objectives and is

conducive to the competitiveness of

the industry. This consultation is a

follow-up to a consultation that took

place earlier this year on E-money and

mobile operators, and is an important

element of the review.

The European Commission intends to

produce a report containing

recommendations arising from the

consultation by Spring 2006. As the

FSA's current stance is to encourage

competition and development through

minimal regulation, it will be

interesting to see whether this remains

the case following the consultation.

Misrepresentation and

financial products - the risks

The recently reported case of Peekay

Intermark Limited v Australia and New

Zealand Banking Group Limited may

be of some significance to institutions

that sell investment products. The High

Court's judgment highlights the issue

that those persons or firms who sell

investment products cannot be certain

that receiving signed final terms and

conditions from a client will protect

them from liability if they gave

misleading information before the sale

was concluded. It is essential to ensure

that marketing, structuring and backoffice functions verify that accurate

product details are communicated to

investors at all stages of the transaction.

In Peekay a company director signed

terms and conditions relating to an

investment which was fundamentally

different from the investment that had

been orally explained to him. Despite

the fact that he had signed explicit

terms and conditions the court found in

favour of the director and held that he

had relied on the prior oral

representation - meaning that the

person who sold him the investment had

misrepresented the investment in

question.

Forthcoming K&LNG

financial services event

in London

18 January 2006

K&LNG International Investment

Compliance Seminar

Landmark Hotel, 222 Marylebone Rd,

London.

For further details please contact

Kathie Lowe at klowe@klng.com

8

WINTER 2005

As a principle of law, a

misrepresentation is an untrue

statement of fact or law made by one

party to another party and which

induces the second party to enter a

contract, thereby causing that second

party loss. Misrepresentation can be

fraudulent, if it is a false representation

made knowingly, or without belief in its

truth, or recklessly as to its truth; or

negligent if it is made carelessly or

without reasonable grounds for

believing its truth; innocent where the

misrepresentation is made without fault.

The remedies for misrepresentation are

either that the contract can be rescinded

and/or that the court will award the party

that suffers loss damages - paid by the

party that made the misrepresentation.

For fraudulent and negligent

misrepresentation, the claimant may

claim both rescission and damages. For

innocent misrepresentation, the court

has a discretion to award damages in the

place of rescission; the court cannot

award both.

When assessing damages for

misrepresentation, the court will

attempt to place the claimant in the

position as if the misrepresentation had

never been made. Hence, in Peekay,

the court awarded damages equal to the

difference between the sum initially

invested in the product and the value

ultimately realised from it.

This case underlines the importance of

supplying an investor with accurate

information throughout the transaction.

An investor can sign a document

without having read it, in the

understanding that he is investing in the

product as described to him, and then

sue the seller if the product later differs

from what was expected. Clearly there is

a potential for a careless seller to be

liable for substantial damages.

www.klng.com

Proposed changes to the

Consumer Credit Act

The Consumer Credit Bill (the "Bill")

was introduced to the House of

Commons in December 2004 following

an extensive consultation period with

industry, regulators and consumer

groups. It is expected that it will

become law in Summer 2006. The Bill

aims to modernise the provisions of the

Consumer Credit Act 1974 (the "CCA")

to establish a fairer and more transparent

regime.

The proposed changes are intended to

improve consumer rights, enhance the

regulation of consumer credit and make

regulation more relevant. The

government is also currently addressing

the issue of double regulation as certain

categories of credit come within the

ambit of both the CCA, and the

Financial Services and Markets Act 2000

("FSMA"). HM Treasury and the

Department of Trade and Industry have

recently issued an informal discussion

paper and draft statutory instrument

('SI') on this subject.

Currently the CCA regulates the supply

of credit to individuals (including

natural persons, unincorporated

associations and partnerships) where the

credit or payments for hire do not

exceed £25,000. The Bill aims to:

require the lender in a consumer

credit agreement to give the borrower

more detailed information concerning

his account throughout the

agreement;

replace the current rules on

extortionate credit bargains with a

new unfair credit relationships test;

reform the licensing system and

introduce a FSMA-style requirement

for applicants to be 'fit and proper'

persons;

grant the Office of Fair Trading

greater powers to supervise licence

holders to ensure compliance with the

regime; and

introduce a Consumer Credit Appeal

Tribunal - a forum for alternative

dispute resolution.

remove the £25,000 limit, so as to

regulate all lending to individuals

(excluding mortgages already

regulated by the FSA);

exclude partnerships with four or

more members from the definition of

'individuals';

no longer apply to a credit agreement

exceeding £25,000 where the

agreement is entered into

predominantly for the purpose of a

business carried on by the borrower,

and the borrower completes a

declaration confirming this;

introduce an exemption from certain

parts of the CCA for loans to high net

worth individuals;

Double regulation

When the FSA's mortgage regulatory

regime was introduced in October 2004

changes were made to the CCA to avoid

situations where lenders were forced to

comply with both the CCA and the FSA

regime. However, two situations remain

where both regimes could apply:

Modified agreements - which exist

where a consumer credit agreement

is modified in such a way as to make

it an FSA regulated mortgage

contract ("RMC"). Currently, the

CCA states that where an existing

credit agreement is varied or

supplemented by a new contract,

they two agreements are to be

treated as one combined agreement.

The SI plans to disapply the CCA

from RMCs, thereby keeping the

agreements separate, so that RMCs

will be subject to FSMA, and the

original agreement would remain

subject to the CCA in these cases.

Credit Brokerage - in cases where

mortgage arrangers, debt adjusters or

debt counsellors broker credit for a

RMC greater than £25,000. The SI

will exempt mortgage brokers, debt

adjusters and debt counsellors from

requiring a consumer credit licence

for broking FSMA regulated

mortgages.

It is hoped that the SI will remove any

confusion and the issue of double

regulation when it becomes law later

this year.

WINTER 2005

9

Take Stock

New company reporting

regulations from the DTI

The 'Shell

reserves affair'

Three new company reporting

regulations came into effect on 1

October 2005 amending the

requirements of the Companies Act

1985 ("CA") dealing with summary

financial statements, the revision of

defective accounts, and other matters

concerning small companies. The three

regulations are:

The 'Shell reserves affair' of 2004

inevitably attracted the attention of

regulators on both sides of the Atlantic.

In an effort to draw a line under the

episode, Shell cooperated closely with

the FSA when it launched its

investigation into Shell's breach of

market abuse provisions of FSMA, as

well as the UKLA Listing Rules. After

concluding a 'concertinaed' procedure,

the FSA imposed its largest ever fine of

£17 million on Shell as a result of the

episode, and in the US, Shell agreed to

pay a civil penalty of $120 million.

The Companies Act 1985

(Investment Companies and

Accounting and Audit Amendments)

Regulations 2005, available from

http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si2005/2005

2280.htm

extend the option to prepare and

distribute summary financial

statements to all companies with

audited accounts;

ensure that companies that use

International Financial Reporting

Standards to prepare their accounts

can still prepare summary financial

statements;

amend and clarify one aspect of the

distribution provisions applying to

investment companies to ensure that

recent accounting changes do not

disrupt dividend practices;

The Companies (Summary Financial

Statements) (Amendment)

Regulations 2005, available from

http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si2005/2005

2281.htm

clarify procedures for companies

wishing to revise their Operating and

Financial Review and Directors'

Remuneration Report when errors

have been made; and

The Companies (Revision of

Defective Accounts and Report)

(Amendment) Regulations 2005,

available from

http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si2005/2005

2282.htm

bring forward the effective date for

Directors' report exemptions to years

beginning on or after 1 January 2005.

The regulations will:

reflect the recent change to the CA

removing the requirement for a

summarised directors' report in a

summary financial statement;

10

WINTER 2005

However, one person who was not

satisfied with the quick conclusion of

the FSA investigation was Sir Philip

Watts. As the chairman of Shell prior to

his resignation on 3 March 2004, he felt

implicated in the investigation into

Shell, particularly as the FSA had

begun a separate investigation into his

own actions. While Shell had opted to

accept the FSA's findings and move on,

Sir Philip attempted to fight the

proceedings regarding Shell, in

addition to his own.

continued on page 12

www.klng.com

D&O Insurance cover - myths and realities

The Equitable Life saga, and the court

action against 15 of its former executive

and non-executive directors, is a

salutary reminder of the importance of

sufficient and effective directors and

officers ("D&O") cover. The mere fact

that D&O cover is in place offers no

guarantee to senior executives that their

costs and liabilities will be covered in

the event that the regulators come

knocking or their name appears in court

proceedings.

The type and level of D&O cover

provided varies enormously in practice

and there may be exclusions and

conditions imposed by insurers which

prove extremely disadvantageous. It is

not just the headline exclusions and

conditions which can give insurers a

potential route to avoid cover. All too

often the fine print of the policy has not

been fully understood (or even read) by

the insured parties nor by their brokers.

That fine print is written by lawyers for

insurers and is often negotiable, just

like any other commercial contract.

The wording of D&O policies varies

from insurer to insurer and the effect, if

not understood, can be catastrophic. For

example, not understanding and

complying fully with the strict

notification provisions of a policy

recently led to a client being unable to

obtain cover under its D&O policy

which otherwise would have been

available.

There may also be potential gaps

between the cover provided by the

D&O policy and the indemnification

provided by the company, particularly

as a result of the recent changes under

English law in relation to director

indemnification. It is essential that the

D&O policy reflects the

indemnification which the company has

agreed to provide and responds where

the company does not.

If you would like a review of your D&O

cover, either now or in the run up to

renewal, please contact Jane HarteLovelace on 020 7360 8172 (jhartelovelace@klng.com) or Sarah Turpin on

020 7360 8285 (sturpin@klng.com) in

our London Insurance Coverage Group.

Alternatively, if you would like to

attend the D&O seminar we are

planning for early 2006 please let us

know.

MiFID and the FSA's discussion paper on

bond market transparency

As discussed in the last edition of Take

Stock, the Markets in Financial

Instruments Directive ('MiFID') will

introduce, with effect from April 2007,

a pan-EU transparency regime for share

trading. It is likely that this regime will

be extended to also cover bonds. As a

result, the FSA has issued a discussion

paper entitled "Trading transparency in

the UK secondary bond markets".

MiFID requires the European

Commission to hold a review of trading

transparency in the secondary bond

markets. The UK is one of the world's

leading bond trading centres, and both

issuers and investors can constructively

contribute to this review through the

FSA's consultation. The paper

concerns the cash markets for bonds;

related derivatives may be considered

later. It focuses on the risks relevant to

the FSA's roles in protecting investors

and ensuring market confidence. The

paper deals with bond markets in the

UK, the levels of transparency in the

UK's secondary bond markets, the

existence of any market transparency

failures in the UK and practical

considerations for policy development.

The key questions the FSA would like

comment on are:

Are there any market failures in

bond markets? If so, what are they

and how do they arise?

How efficient is the price-formation

process for different bonds?

Do you perceive any difficulties or

concerns with best execution in

bond markets?

Do retail investors face any particular

difficulties in participating in bond

markets?

To what extent might greater

transparency be a solution to market

failures?

What is the relationship between

transparency and liquidity in bond

markets?

WINTER 2005

11

www.klng.com

Continued from page 10

Shell (continued)

Could a pre or post-trade

transparency requirement for a

defined set of benchmark bonds have

beneficial effects for other bonds?

Would greater transparency in bond

markets bring any wider benefits?

How does the inter-relationship

between trading in the cash and

derivatives markets affect the

consideration of these issues?

What practical issues do you think

are important for regulators to

consider in formulating policy in

relation to transparency in bond

markets? What costs do you foresee?

The full paper can be downloaded from

http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pages/Library/Po

licy/ DP/2005/05_05.shtml and there is

a deadline of 5 December for responses.

Sir Philip claimed that the FSA had not

respected its rules regarding notice of

decisions when concluding the

investigation into Shell. Under FSMA

if the FSA sends a notice to the subject

of an investigation, and the notice

identifies and is prejudicial to a third

party, then the FSA must send a copy

of the notice to that third party, and

allow them to make representations on

it.

In a reference to the Financial Services

and Markets Tribunal (the "Tribunal"),

the appeal body for FSA decisions, Sir

Philip argued that the decision notices

sent to Shell identified him, and hence

the FSA was obliged to send a copy of

the notices to him, allowing him time

to make representations on them. He

further suggested that he was seen as

responsible by the public for the

misstatement of reserves. He argued

that as a result, the decision notice sent

to Shell at the conclusion of the FSA

investigation identified him, and was

prejudicial to him, even though he was

not explicitly mentioned by name, or

even by job title.

The Tribunal accepted that Sir Philip

had been the subject of significant

adverse comment in the press as a

result of the affair, but did not accept

his arguments. If his arguments were

correct, then the FSA could be obliged

to extend the third person rights to the

whole board, and perhaps other

employees, of a company being

investigated. The Tribunal decided

that the decision notice was addressed

to Shell alone and there was no reason

to assume that it concerned Sir Philip.

Even though Sir Philip and Shell

received a lot of press attention, the

FSA is still not obliged to offer a third

party protection and the right to make

representations to the Tribunal, unless

that third party is specifically identified

in the notice.

Kirkpatrick & Lockhart

Who to Contact

Nicholson Graham LLP

For further information contact the following

110 Cannon Street

London EC4N 6AR

Philip Morgan

Neil Robson

www.klng.com

pmorgan@klng.com

nrobson@klng.com

T: +44 (0)20 7648 9000

T: +44 (0)20 7360 8123

T: +44 (0)20 7360 8130

F: +44 (0)20 7648 9001

Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham (K&LNG) has approximately 1,000 lawyers and represents entrepreneurs, growth and middle market

companies, capital markets participants, and leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100 global corporations nationally and internationally.

K&LNG is a combination of two limited liability partnerships, each named Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP, one qualified in Delaware, U.S.A.

and practicing from offices in Boston, Dallas, Harrisburg, Los Angeles, Miami, Newark, New York, Palo Alto, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and Washington

and one incorporated in England practicing from the London office.

This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied

upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer

.Data Protection Act 1998 - We may contact you from time to time with information on Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP seminars and with

our regular newsletters, which may be of interest to you. We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail cgregory@klng.com if you

would prefer not to receive this information.

© 2005 KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART NICHOLSON GRAHAM LLP. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

WINTER 2005

12