Internal Control Weakness and Information Quality Abstract

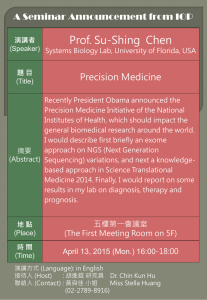

advertisement