Design Exploring the

advertisement

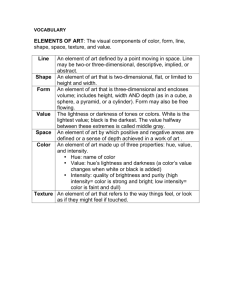

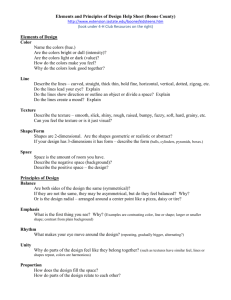

Design Exploring the Elements & Principles Elements of Design A design is a visual plan you can use to create your 4-H project. Everything you can see has a design. When you describe something you see, you use words that tell about the lines, shapes, colors, textures, and spaces. Line, shape, color, texture, and space are the basic elements of design. The elements of design are important to everyone who works in textiles and clothing, home interiors, woodworking, photography, landscaping, architecture, foods, and the visual arts. If you understand the design elements, you will be more successful with your 4-H projects. Line Lines can be horizontal, vertical, dotted, zig-zag, curved, straight, diagonal, bold, or fine. Lines can show direction, lead the eye, outline an object, divide a space, and communicate a feeling or emotion. Shape Shapes are made by connecting lines. Circle, square, triangle, and freeform are words used to identify shapes. Look at the objects around you and describe their basic shapes. Are they one shape, or are they a combination of many shapes? After doing this several times, you will begin to understand what shape really is. Line creates two dimensional or flat shapes. When shapes are three dimensional, we call them forms. A circle is a shape; a ball is a form. A square is a shape; a cube is a form. A drawing is a flat shape; a sculpture is a three-dimensional form. 4-H 634 March 2000 Color Space Color is described with the words hue, value, and intensity. Hue refers to the name of the color—red or blue, for example. Value tells the lightness or darkness of a hue. Intensity refers to the brightness or dullness of a hue. You can use a color wheel and learn how colors work together in the publication, 4H-633, Color. Space refers to the area that a shape or form occupies. It also refers to the background against which we see the shape or form. Space can be defined as positive and negative. The positive space of a design is the filled space in the design—often it is the shapes that make up the design. Negative space is the background. The negative space in design is as important as the positive area. Texture Texture is the surface quality of an item. It’s how something feels when touched, or looks like it would feel if touched. Sandpaper is rough. Velvet is smooth. A drawing of a tree stump could show rough outer bark and a smooth inner surface. Search for ways to add texture to your projects. Texture adds variety and interest. Principles of Design Some combinations of design elements (line, shape, color, texture, and space) work better than others. Here are some guidelines to help you understand why some combinations work and others do not work as well. These guidelines—rhythm, proportion, emphasis, balance, and unity—are the principles of design. Rhythm You have felt rhythm in music. Rhythm is also a part of things you see. It allows the eye to move from one part of a design to another part. Rhythm can be created by: • Repeating a color, shape, texture, line, or space when designing. • Varying the size of objects, shapes, or lines in sequence (small to large). • Using a progression of colors from tints to shades (light blue to dark blue). • Shifting from one hue to a neighboring hue (yellow to yellow-orange to orange to red-orange to red). Proportion Proportion refers to the relationship between one part of a design and another part or to the whole design. It is a comparison of sizes, shapes, and quantities. For example, the relationship between the vertical and horizontal measurements of a wall hanging may be pleasing because the unequal lengths produce an interesting contrast. Emphasis Every design needs an accent—a point of interest. Emphasis is the quality that draws your attention to a certain part of a design first. There are several ways to create emphasis: • Use a contrasting color. • Use a different or unusual line. • Make a shape very large or very small. • Use a different shape. • Use plain background space. Balance Balance gives a feeling of stability. There are three types of balance. Symmetrical, or formal balance, is the simplest kind. An item that is symmetrically balanced is the same on both sides. Our bodies are an example of formal balance. If you draw an imaginary line from your head to your toes dividing your body in half, you will be pretty much the same on both sides. Designs that have a radial balance have a center point. A tire, pizza, and a daisy flower are all examples of design with radial balance. When you look through a kaleidoscope, everything you see has a radial balance. Asymmetrical balance creates a feeling of equal weight on both sides, even though the sides do not look the same. Asymmetrical designs also are called informal designs because they suggest movement and spontaneity. Asymmetrical balance is the hardest type of balance to achieve and often takes experimenting or moving elements around until balance is achieved. Unity When things look right together, you have created unity or harmony. Lines and shapes that repeat each other show unity (curved lines with curved shapes). Colors that have a common hue are harmonious. Textures that have a similar feel add to unity. But too much uniformity sometimes can be boring. At the same time, too much variety destroys unity. Honesty of Design Honesty of design refers to three specific areas— media, form, and function. You are being honest with a medium when you are familiar with that medium, use it to its best advantage, and avoid making it look like something else. Clay should not be glazed to look like wood, and wood should not be painted to look like clay bricks. Honesty related to form and function means that parts of a design should work in ways they were intended. Doors on woodworking projects should not be fake; they should open. A flower pot should be designed to complement the flowers and not draw more attention to the pot. Ideas and Inspirations Where do you get your ideas? Just as you do not copy from the encyclopedia when you write a term paper or from another person’s paper when you take a test, you should never copy another person’s design. You are what makes your designs special! Inspiration or sources for designs may come from poetry, music, nature, and your own photographs and sketches. Let these inspirations be springboards for your imagination. Evaluating Design Evaluating your designs and those of others can help you improve your understanding about design. You can get help in evaluating your work from many people, among them your parents, other 4-H’ers, leaders, teachers, and fair judges. There is seldom only one way to improve a design, so don’t be surprised if different people have different ideas on how you might change your work. In the end, the decision is yours. Becoming a good designer takes practice. The more you talk about and play with the elements and principles of design, the easier it will be to use them effectively. Here are some questions to ask yourself about your designs. 1. Where did you get the idea for your design? 2. Describe one of the design elements. How did you use it? 3. What do you like about the way your design looks? 4. What might you change another time? 5. Is your design honest in media, form, and function? Additional Resources These additional resources are available from your ISU Extension county office: Color, 4H 633 Selecting Quality Crafts, PM 962 Written by JaneAnn Stout, former ISU Extension art and design specialist. Edited by Carol Ouverson, communication specialist. . . . and justice for all The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Many materials can be made available in alternative formats for ADA clients. To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call 202-720-5964. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Jack M. Payne, director, Cooperative Extension Service, Iowa State University of Science and Technology, Ames, Iowa. 1/08