Soft Landing in Cuba? Emerging Entrepreneurs and Middle Classes

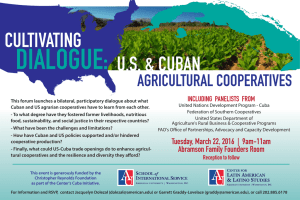

advertisement