ACCessible PubliC Rights-of-WAy Public Rights-of-Way Access Advisor y Committee Special Report: July

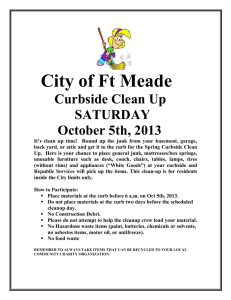

advertisement