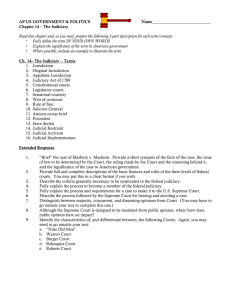

Michael S. Greco President-Elect Nominee, American Bar Association The Stanley Lecture

advertisement

Michael S. Greco President-Elect Nominee, American Bar Association The Stanley Lecture Connecticut Judges Institute Quinnipiac Law School Hamden, Connecticut - June 17, 2004 “The Role of the Judge at the Dawn of the 21st Century: A Lawyer’s Perspective” It is a pleasure for me, as a Massachusetts lawyer, and an American Bar Association officer, to be with you at this meeting of the Connecticut Judges Institute. The rich history of the American Bar Association has its roots here in Connecticut. Simeon E. Baldwin, a member of the Connecticut Bar Association, is widely credited as the founder of the ABA. In 1878 he proposed to the Connecticut Bar Association the formation of a national bar association, and on his motion a committee of three was appointed to explore the possibility. That committee consisted of three prominent Connecticut lawyers – Richard D. Hubbard, then Governor of Connecticut, Simeon Baldwin, then on the faculty of Yale Law School, and William Hamersley, who later became a justice on the Connecticut Supreme Court. About 100 lawyers from 21 states met on August 21, 1878, in Saratoga Springs, NY, to discuss the feasibility of the idea. The American Bar Association was born at that meeting. Simeon Baldwin, who in 1893 was appointed to the Connecticut Supreme Court of Errors, and became Chief Justice in 1907, served as president of the ABA from 1890-1891. I will be honored to follow in his footsteps, and those of 127 other predecessors, when I become president of the association in August 2005. It is particularly appropriate for me to be here today to discuss the challenges that today face the judiciary, because Connecticut has been preparing leaders for challenges in the legal profession longer than any other state in the union, and early on helped to shape the judiciary of the young nation. Tapping Reeve, a resident of Litchfield, first began formal institutional instruction in the law in 1784. His law school revolutionized the method of instruction in the study of law. The school’s early graduates included John C. Calhoun, Aaron Burr, Horace Mann, Oliver Wolcott, Jr., and Noah Webster. Oliver Ellsworth, while serving as a U.S. Senator from Connecticut on the Judiciary Committee, was principal author of the Judiciary Act of 1789. He was also the first Connecticut lawyer to serve as Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, and was the nation’s third Chief Justice, immediately preceding John Marshall. This morning I want to address what I believe to be the role of the judge in these times of unprecedented challenge for our nation and the judiciary. As a member of the bar and citizen, I have great respect for the judiciary, and an abiding interest in its role in our democracy. During my 32 years at the bar I have been involved with the judiciary in various contexts: as a trial lawyer in state and federal courts; as a member for eight years of the Massachusetts (Republican) Governor’s State Court Judicial Nominating Council, which assisted the governor in making several hundred merit-based judicial appointments; as a member of U.S. Senators Kennedy and Kerry’s Federal Court Judicial Selection Commission, which recommended the five new Massachusetts federal district judges confirmed in 1993; and as member for three years and then chair of the ABA Standing Committee on Federal Judiciary, which evaluates the qualifications of the President’s federal court nominees. Two years ago I also chaired the ABA’s Task Force on State Judicial Selection and Campaigns, which studied judicial elections in the 38 states that elect their judges. The Task Force documented the effect on the public’s trust and confidence in judges resulting from negative and shocking campaign advertising; from unprecedented spending by judicial candidates; and from unprecedented spending by interest groups such as chambers of commerce and associations of trial lawyers. As you may know, the ABA has no Political Action Committee or PAC, and the ABA neither nominates nor supports judicial or political candidates. The mounting pressures on the judiciary from various quarters, and the insufficient and progressively decreasing resources being provided by legislatures to the judiciary throughout the country to serve justice, give me serious concern. Later in these remarks I will indicate what the American Bar Association is doing to address some of these pressures and challenges. As members of the judiciary, you no doubt recognize the importance of an independent and impartial judicial branch. The judiciary helped to shape the foundation and then the direction of our country by maintaining an unwavering commitment to the Rule of Law, and to the principles of an independent judiciary. Yet, throughout our nation’s history, challenges to the independence of the judiciary have threatened to weaken the vital role that the courts have in our republican system of government. Those challenges have never been more serious than they are today. Judicial independence is the bedrock principle of our democratic republic. Judicial independence provides for a judiciary free from partisan influences --- a judiciary that impartially and fairly applies the facts of a case to the applicable law. Our country’s Founding Fathers created a system of government unique in its design and devoted to protecting the rights and liberties of all. 2 Each of the three branches has specific duties and responsibilities, and a system of checks and balances was created to ensure that no single branch would dominate the government. Clearly, the crucial part of this governmental structure is an independent judiciary. John Adams, distinguished Boston lawyer, a founder of our democratic form of government, and later our second president, drafted the Massachusetts Constitution, which in turn served as the basis for our federal constitution. Adams clearly recognized the vital role that an independent judiciary has in our democracy when he wrote that democracy depends on an “able and impartial administration of justice,” and on a judiciary that is “subservient to none.” That notion is embedded in the Massachusetts Constitution in the following clause: It is essential to the preservation of rights of every individual, his life, liberty, property and character, that there be an impartial interpretation of the laws, and administration of justice. It is the right of every citizen to be tried by judges as free, impartial and independent as the lot of humanity will admit. The Rule of Law is another bedrock of our government. It allows all citizens to enjoy the liberty and freedoms guaranteed by our state and federal constitutions, and protects against tyranny of the majority. By interpreting state and federal constitutions, the judicial branch checks the will of the legislature, and the excesses of the executive, to ensure that all citizens, whether part of the majority or not, are allowed equal access to all the rights and liberties guaranteed them by the constitution. A judge’s impartiality and ability to interpret and apply the laws fairly are integral to the administration of justice. Without judicial independence, there can be no protection of individual rights. Without judicial independence, there can be no safe harbor for the oppressed --the minority. Without judicial independence, there can be no check on government leaders or corporate actors. Without judicial independence there would be no democracy. Our laws --- laws that are meant to protect everyone --- the rich and the poor, the majority and the minority, the powerful and the powerless --- can only function if the judicial system is independent, impartial and, equally important in my view, courageous. Speaking on the importance of impartiality in a judge, Chief Justice Rehnquist has said, “A judge is bound to decide each case fairly, in accord with the relevant facts and the applicable law, even when the decision is not the one the home crowd wants.” 3 Worrying about the reaction of the “home crowd” compromises both impartiality and integrity in a judge. Retired Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Edward F. Hennessey, commenting on Chief Justice Rehnquist’s notion, has observed that the “home crowd” can take many forms: “it may be the clamor of the news media, or the noise of pressure groups. In states that elect their judges, it may be the expectation of a lawyer who has contributed to the judge’s election fund.” In states that elect judges, the “home crowd” certainly includes the voters, who can vote a judge out of office for rendering an unpopular decision. Only the judge himself or herself can ensure, as a matter of personal conscience, and the ethical and sacred responsibilities of the judicial office, that impartiality has prevailed over concern about the “home crowd’s” reaction. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes spoke in these terms about the importance of courage in a judge, and the judge’s pursuit of truth: I get letters, not always anonymous, intimating that we are corrupt. Well, gentlemen, I admit that it makes my heart ache. It is very painful when one spends all the energies of one’s soul in trying to do good work, with no thought but that of solving a problem according to the rules by which one is bound, to know that many see sinister motives and would be glad to find evidence that one was consciously bad. But we must take such things philosophically and try to see what we can learn from the hatred and distrust, and whether behind them there may not be some germ of inarticulate truth. Such self-evaluation is healthy, to be sure, and it should be an on-going process for judges, as well as lawyers. But in the end it should not serve to hinder or overcome the judge’s self-confidence that he or she has discharged his or her obligation, in Chief Justice Rehnquist’s words, “to decide the case fairly, in accord with the relevant facts and the applicable law.” As the U.S. Supreme Court observed in Chambers v. Florida, courts serve as “havens of refuge for those who might otherwise suffer because they are helpless, weak, outnumbered or because they are nonconforming victims of prejudice and public excitement.” Day in and day out, judges in our country – over 25,000 in the state court system alone – hear hundreds and even thousands of cases. And each day courageous judges throughout our judicial system uphold the Rule of Law and administer justice, even when the law itself is unpopular, or the facts shock the public, or the case is notorious. It takes a judiciary comprised of strong, courageous and independent judges to maintain the Rule of Law while also maintaining the “home crowd’s” respect for the 4 administration of justice. But it is the solemn obligation of each judge, to the people and to our democracy, to do just that. During the Civil Rights era in this country, federal district judges issued school desegregation orders, ordered police protection for protestors, and worked to curb racial discrimination in the jury process, to name just a few issues. These tireless judges, dubbed the “58 Lonely Men” in Jack Peltason’s seminal book, enforced civil rights legislation at great personal peril. Their dedication to the Rule of Law, even at personal cost or harm, is an inspiring example to all who wear the judicial robe. This year marks the historic fiftieth anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. That landmark case overturned the concept of “separate but equal” and paved the way for eliminating all forms of state-sponsored segregation in public facilities, from schools to buses. The Civil Rights battles were rife with protests, dissent, and assassination. Yet the courts, through a series of important decisions, stayed the course and continued to apply the Rule of Law, without falling prey to the cries of popular protest. In 1985, while serving as president of the Massachusetts Bar Association, I was honored to present the President’s Award to a courageous federal district judge, W. Arthur Garrity, Jr., who decided and then for many years monitored the Boston schools desegregation case. The judge and I lived in the same town, Wellesley, and rode the same commuter train daily, during the tumultuous early 1970’s when he presided over that case. At the time I was a young lawyer, recently admitted to the bar. I remember seeing Judge Garrity on the commuter train most mornings, knowing that his home was under 24-hour protection. I remember watching the Judge as he read the Boston Globe on the train, along with the rest of us, all of us reading on the Globe’s front page lead stories helpfully informing Judge Garrity as to how he would rule on this or that matter that day in the trial (in case he were in doubt as to what he was to do). But most of all, I recall the calmness of Judge Garrity, his resolve, and the courage that he displayed under immense pressure both during and after the trial. The “home crowd” then was decidedly hostile. Judge Garrity never showed publicly any effects of that hostility towards him. His courage never wavered. His positive influence on public school education for all children in the city of Boston is his enduring legacy. It was for those reasons that the Massachusetts Bar Association presented the President’s Award to Judge Garrity. The issue of “separate but equal” continues today in my hometown of Boston, where our Supreme Judicial Court has come under great pressure from segments of the public, our governor, and even the President of the United States regarding the Court’s interpretation of the Massachusetts Constitution with respect to the rights of gay men and women to marry. 5 Those opponents of the Court’s decision – part of today’s “home crowd” -- have decried the Court’s purported “judicial activism,” and some have even demanded the impeachment of the four Justices who ruled in the 4-3 majority. The Massachusetts Legislature, meeting in Constitutional Convention, considered amendments to the constitution relating not only to marriage, but also calling, ill-advisedly in my view, for the election of judges, so that judges in the future would be more accountable to the will of the public when they render unpopular decisions. The controversy continues to rage in Massachusetts – and rage is the operative word. Rage from the business community towards that dreaded “judicial activism” – a phrase that appears intended to connote a medical disorder as well as legal disorder – can be seen in the aggressive campaign now being waged by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce against judges and lawyers. In recent newspaper ads and its website, the Chamber attacks the legal system, and “activist” judges, for “abuses of the class action system” and the filing of “frivolous suits” that are “costly to business and consumers”. The Chamber claims that an opinion poll, which it commissioned, reported that such lawsuits allegedly cost the nation $809 per person each year. While that figure is debunked by experts, in the last two state judicial election cycles the Chamber boasted of its success, by spending millions of dollars in media ads, in influencing voters to elect judges who will support the Chamber’s political agenda. A 2001 ABA report on public confidence in the judiciary in states where judges are elected indicated that such ads – especially on television – are causing great harm to the public’s trust of judges. For example, the report cited a Texas Supreme Court survey that found that 83 percent of Texas adults, and 79 percent of Texas lawyers, believed that judicial campaign contributions influenced judicial decisions “very significantly” or “fairly significantly”. Perhaps the most distressing statistic of all was that 48 percent of the judges surveyed believed that campaign contributions influenced judicial decisions. What of judicial impartiality? Judicial independence? The Rule of Law? As many of you are aware, we recently marked the fortieth anniversary of another very important judicial decision: Gideon v. Wainwright. The right to counsel in a criminal trial was found to be fundamental in federal criminal proceedings as far back as 1932, yet it was not until 1963 that the US Supreme Court ruled that the right to counsel guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment extends to all persons accused of crime. Gideon exemplifies the concept that rights and liberties in this country are afforded to all people, regardless of race, or wealth. And its importance was reinforced by the fact that Abe Fortas, a leading lawyer in the country at the time, and later a US Supreme Court Associate Justice, served as counsel, on a pro bono basis, for Clarence Gideon. Today, we must continue our vigilance in assuring that every person has 6 access to competent, effective assistance of counsel to protect constitutional rights. I believe that our democracy depends on it. Today we live in a world punctuated by acts of terror, in a country that is struggling to balance national security and the protection of the civil liberties that have defined us for the freedom-loving, and the freedom-hating, countries of the world. Today’s acts of terror have analogues in our nation’s history – there were comparable acts of terrorism, for example, during the American Revolution, the Civil War, and the War of 1812 when the White House was evacuated and burned to the ground. The role of the judiciary at such times of crisis in finding the reasonable constitutional balance is crucial not only to the rights of those suspected of the acts of terrorism, but to the rights of all American citizens, and to the survival of democracy. The right to effective counsel today is under increased scrutiny as applied to those individuals being detained by the Department of Homeland Security. Immigration issues and the ability of the government to administer homeland security measures challenge judges to balance fundamental rights with the necessity for the government to protect its citizens. In times of national crisis, there is tremendous pressure on the judiciary to give great deference to the executive branch. Yet it is vitally important that we remember that the U.S. Constitution can handle crisis and emergency. The last thing we in this country should do is signal to the world that we do not have enough confidence in our democratic institutions – in our courts -to deal with the crisis of these times. To send that signal is to inflict on ourselves and on our democracy the very harm – the lasting harm -- to our country that the terrorists hope to accomplish. Chief Justice Rehnquist last month addressed the American Law Institute annual meeting in Washington, D.C., a meeting that I attended. I believe that his remarks have relevance to the current treatment of enemy combatants by our government, and to the war on terrorism in general. The subject of the Chief Justice’s speech was the Nuremberg War Criminal Trials in November 1945, following the end of World War II, and in particular the role of US Supreme Court Associate Justice Robert H. Jackson in those proceedings. You may recall that Justice Jackson took a controversial one-year leave of absence from the Supreme Court, organized the Nuremberg Tribunal itself, and then served as chief prosecutor in the trials of the twenty-two defendants. Of the twenty-two, twelve were sentenced to hang, seven were imprisoned, and three were acquitted. It is from Jackson’s opening statement to the Nurenberg Tribunal that Chief Justice Rehnquist quoted. In clear and eloquent prose Jackson spoke of the importance of ensuring that each defendant, no matter how heinous the charges, receive a fair trial. He said this: 7 The former high station of these defendants, the notoriety of their acts, and the adaptability of their conduct to provoke retaliation, make it hard to distinguish between the demand for a just and measured retribution, and the unthinking cry for vengeance which arises from the anguish of war. It is our task, so far as humanly possible, to draw the line between the two. We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow. To pass these defendants a poisoned chalice is to put it to our own lips as well. We must summon such detachment and intellectual integrity to our task that this trial will commend itself to posterity as fulfilling humanity’s aspirations to do justice. The American Bar Association’s policy positions to date on the use of military tribunals, the treatment of “enemy combatants” and immigrants, and the war on terrorism reflect the wisdom contained in those words, words that must continue to be as operative today as they were in 1945. The ABA believes that Justice Jackson’s phrase, “fulfilling humanity’s aspirations to do justice”, describes the over-arching purpose of the Bill of Rights, which we must never allow to be compromised. The people look to Congress and the Executive to ensure our national security. But the people look to the Judiciary to ensure that those national security efforts do not erode or destroy our constitutional rights. If the Judiciary abdicates its responsibility, under the inevitable, constant, and strong pressure from the Executive Branch, our freedoms suffer, and so does democracy. In the words of John Adams, democracy depends on a judiciary that is “subservient to none.” The Founders knew that they were building in tension among the three branches of government in the new democracy they created, but they knew also that it is that very tension that helps guarantee the checks and balances on which democracy depends. As was the case during the Civil Rights era, judges must be courageous, willing to uphold the Rule of Law and protect the rights of all citizens, and fulfill “humanity’s aspirations to do justice.” I believe that the greatest danger to democracy is not an overzealous Executive branch, but a subservient Judicial branch. Each branch of government has a vital role to play, and each was given a balancing power in our democracy. The balance is broken when judges become passive or submissive, or when they too quickly yield their powers of analysis, training, and responsibility to do justice, to another branch of government that in its zealousness may be over-reaching or exceeding its constitutional boundaries. The judiciary’s critical role, never more so than in post-September 11 America, is to prevent that over-reaching and those excesses of power. Immigration issues, civil rights, criminal justice issues and environmental issues are among the wide-ranging challenges that courts are called upon to resolve each day. And in the dawn of this new century we are witnessing ever faster-advancing communication and information technology, from e-commerce to e-litigation, and an 8 increasingly globalized economy that increasingly will generate multinational disputes and multinational judicial proceedings, making the judge’s work even more daunting. And yet, judges, on both the state and federal level, now increasingly face a whole series of procedural and resource obstacles that are negatively impacting their ability to function independently and impartially. Many of these challenges threaten to disrupt the basic purpose of the courts – to ensure that all citizens enjoy the liberties and freedoms guaranteed by the constitution. Examples of these obstacles abound. Budget cuts have forced some states to close courthouses, limit hours of public access, delay processing of all but the most serious criminal cases, lay off large numbers of court employees, and eliminate innovative programs that help reduce recidivism and chemical dependency. Courts are being challenged to become more accessible to the public, whether through providing more assistance for pro se litigants, making the courts more userfriendly, providing faster access to filings, forms and decisions, or providing access to the courthouse for disabled persons. Often these changes must be implemented while courts are fighting shrinking budgets, greater workloads, and less staff resources. Lack of diversity in the courts feeds the perception that there are two systems of justice emerging in the United States: one for the rich and powerful, and one for everyone else. Judicial disciplinary systems in some states are viewed as ineffectual, contributing to a public perception that judges are unaccountable and untouchable. Judicial selection systems, too, bring with them a host of issues. Roscoe Pound, almost a century ago, gave an address to the American Bar Association Annual Meeting in 1906 entitled “The Causes of Popular Dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice.” In this seminal speech, Pound warned that traditional respect for the bench can be destroyed by the “putting of our courts into politics” and “compelling judges to become politicians.” These words of Dean Pound ring true today, just as they did a century ago, when we consider the dangers of forcing judges to behave more like politicians – to adhere to a political philosophy or ideology, to cater to a particular demographic, or to support a particular viewpoint. In states that elect judges, campaign costs and acrimony have skyrocketed. Today it is commonplace for judicial candidates in a statewide race to raise and spend more than a million dollars in campaign funds, which increasingly are being used to fuel intensely negative media ads that have the effect of eroding public confidence and trust in the integrity and fairness of our state courts. We know all too well from experiences 9 in other parts of the world that when the people lose their trust of the courts, chaos reigns and democracy dies. As the principal representative of the legal profession in America, with more than 405,000 members, the ABA has always been, must always be, and we will be, vigilant in our defense of the legal system, and in the defense of a strong and independent judicial branch. A primary goal of the ABA is the preservation of an independent judiciary. To that end, the Association has worked tirelessly over the years to provide programs and policies that address many of the challenges faced by today’s judiciary. I want to share with you a few examples of ABA initiatives aimed at preserving and promoting judicial independence. Last year, the ABA released a report on the 21st Century Judiciary, entitled “Justice in Jeopardy.” This report took a comprehensive look at state judicial systems – including the 38 states where judges are elected -- and recommended a series of improvements to foster an independent, impartial judiciary. In direct response to the report, among a number of initiatives, the ABA appointed a commission to evaluate the ABA Model Code of Judicial Conduct. The commission, which is in the middle of a two-year comprehensive revision of the Code, will consider a wide variety of issues, including whether problem-solving courts require independent ethics provisions, how judicial campaign speech can be regulated, and whether restrictions on a spouse’s political or business activities – from investments to charitable and business activities – should lead to a judge’s recusal. In addition, the ABA is looking closely at judicial compensation, on both the federal and state level. The ABA has lobbied aggressively in Congress in support of increased federal judicial pay and the necessity for regular cost-of-living-adjustments. A report released recently by the ABA, in conjunction with the Federal Bar Association, outlines the dramatic drop in buying power of federal judges that has resulted from limited pay increases. In addition, the ABA has sought to document the number of federal judges who have left the bench due to economic concerns. We will continue to work with the leadership in Congress and the Administration on efforts to secure better pay for the federal judiciary. The Judicial Division of the ABA is also studying compensation issues for the administrative law judiciary. On the state level, the ABA Standing Committee on Judicial Independence has made a series of recommendations to increase state judicial compensation, including the creation of salary commissions. The ABA House of Delegates adopted policy last August that urges states to remove politics from the process of setting state judicial salaries by forming independent, broad-based commissions that have authority to determine compensation levels for state judges. 10 I am pleased to recognize that Connecticut in 1971 established a compensation commission that makes recommendations for salaries on all levels of state government, including the judiciary. This commission, though, serves only an advisory function, and is appointed by only the legislative and executive branches. The ABA policy, specific to judges, calls for these commissions to have the independent authority to determine judicial salaries. In addition, the ABA policy urges states to provide an opportunity for the judiciary to participate in the appointment of members to these commissions. Salary commissions now exist in about twenty states, but only a handful have true independent authority to set salaries. In the recent past, Connecticut judicial salaries ranked in the top 25% nationally, but the comparatively high cost of living in Connecticut reduced the buying power of Superior Court judges’ salaries to a national rank of 39th among the states. It is heartening that Connecticut judges have been granted a significant salary increase for each of the three years starting January 2005. It is an important statement on the vital role that judges have in our system of government. It is my hope that Connecticut’s lead will be followed by other states. At the ABA Annual Meeting last August, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy forcefully and eloquently spoke out against mandatory minimum sentences and sentencing guidelines, as well as racial disparity in our country’s prison population, the conditions in prisons, the use of the pardon process, and the objectives of incarceration. In addition, he focused on and derided the recent challenges to federal judicial discretion. In his remarks, Justice Kennedy challenged the organized bar to suggest reforms. The ABA quickly responded to his challenge, and we will issue a report at our upcoming August 2004 annual meeting in Atlanta. The ABA Standing Committee on Federal Judicial Improvements has also agreed to take on a comprehensive plan to provide public education resources on the importance of judicial independence in the federal judiciary, and how challenges to federal judicial discretion impact the administration of justice. The ABA agrees with Justice Kennedy. The ABA believes that we need to give judges a gavel, not a rubber stamp. Judges need to have discretion to rule on the specific facts – and the humanity -- of a case. Again, I am mindful of John Adams’ exhortation in the Massachusetts Constitution, which served as the model for the US Constitution, that “It is the right of every citizen to be tried by judges as free, impartial and independent as the lot of humanity will admit.” Justice Kennedy has taken a courageous stand to speak out on criminal justice issues that he finds troubling. We should all take to heart his directive to question the benefits to our society from increased incarceration, and the disproportionate impact of criminal sentencing on minority populations. We can never take for granted that the 11 directives of Brown and Gideon, ensuring that the benefits of our constitution are guaranteed to all citizens, will be respected without diligent oversight. As I listened to Justice Kennedy’s speech as a member of the audience, I admired the courage that he demonstrated in criticizing our criminal justice system, the impact of mandatory sentencing on the administration of justice, the deplorable conditions of our prison system, and those who bear the responsibility for creating and solving these problems. He demonstrated classic judicial independence and courage in making his remarks. Justice Kennedy did not just criticize. He offered suggestions, and he challenged. The ABA has taken up his challenge on behalf of the legal profession. So should the executive branch, the legislative branch, and the judiciary. It will take all of us together to fix what is so wrong in America’s criminal justice system. I believe, however, that the judiciary can make an immediate and direct impact in addressing what needs to be done, and in spurring the executive and legislative branches to discharge their responsibilities. Another serious threat to the judiciary today is the decline of trials, due largely on the criminal side to sentencing guidelines and mandatory sentencing and the shift of power or discretion from independent trial judges to prosecutors (the executive branch), and on the civil side to the growth of ADR. Federal judges in Boston, like their counterparts throughout the country, are very concerned about this trend, especially with respect to jury trials, which has long-term implications for the judiciary, the profession, and the justice system. The ABA Litigation Section this year has funded groundbreaking research to document the decline of trials in American courtrooms. The research shows, for example, that the percentage of federal civil cases going to trial has dropped from 11.8% in 1962 to 1.8% in 2002. The ABA will continue to look closely at this subject in the coming year, with the appointment of a blue-ribbon commission on jury trials. Our judicial system, and our country, benefit from the active participation of people from all walks of life. In order to acquaint more young people with the judicial branch, the ABA Judicial Division, in collaboration with other ABA entities including the Commission on Diversity in the Profession, sponsors a judicial-clerkship training program. This flourishing initiative provides minority law students with the opportunity to clerk for judges throughout the country. In turn, the judiciary is introduced to strong, intelligent young men and women who are eager to pursue a career in law. I encourage you to broaden your usual search for good law clerks. A clerkship means a great deal in the development and advancement of young lawyers. I know how much I have benefited from my clerkship in 1972 on the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals. 12 Some of the most serious problems confronting our judicial systems today relate to judicial selection and reselection. Judicial election campaigns at all levels are increasingly focused on isolated issues of intense political interest. Even states where judges are appointed are not immune from pressures to select judges along ideological lines. Nowhere is the tension between judicial independence and judicial accountability more palpable than in the context of judicial selection. Although there is general consensus that selection systems should preserve and promote independence and accountability, determining how to strike that balance in a judicial selection system is subject to intense debate. The ABA strongly advocates for a commission-based appointive system to select state judges. While reform efforts in the states have been stagnant for the past decade, the ABA continues in its efforts to promote improvements to the judicial selection system. In addition, the ABA supports the use of full public financing in states that elect judges. And the ABA supports the creation of neutral, non-partisan bodies to evaluate the qualifications of judicial candidates, regardless of the selection system employed in the state. Challenges to our courts are not unique to modern times. Simeon Baldwin, Tapping Reeve, Roscoe Pound --- leaders in their respective legal communities --recognized the need to organize lawyers, to advocate on behalf of the profession, to improve legal education, to adopt and update codes of professional conduct for lawyers and judges, to help the profession grow, and to achieve improvements in the administration of justice. It is our responsibility, as leaders in today’s legal community, to find innovative solutions to the challenges that are now facing our judicial system. I conclude with these thoughts. The lawyers of America, and particularly the organized bar, must zealously support the judiciary’s independence, and we must ensure that judges have adequate compensation and resources to do their work. This responsibility of lawyers and the bar has never been as pressing as it is at the dawn of this new century and we cannot, and we will not, fail to discharge that responsibility. The ABA believes that, because judges cannot defend themselves in the court of public opinion, it is the lawyers who must speak out and support the judiciary when it is attacked by interest groups or others unhappy with a particular decision. Above all, we must celebrate judges who allow the Rule of Law to flourish in our country when they demonstrate the courage to apply the law to the facts of the case, and to administer justice efficiently and impartially. 13 The greatest democracy the world has ever known continues to flourish only because of the Rule of Law. And there would be no Rule of Law without an independent judiciary and an independent legal profession. I firmly believe, as John Adams recognized at the beginning of this nation, that the viability of our republic depends on an independent and courageous judiciary that is the equal of, and not subservient to, either Congress or the Executive. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the heavy constitutional responsibility that I believe a judge must discharge at the dawn of the 21st Century in America. Thank you for the opportunity to share my thoughts with you. 14