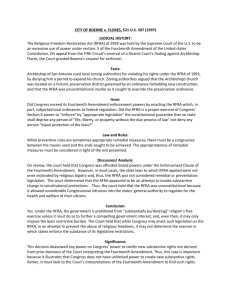

Supreme Court of the United States In The

advertisement