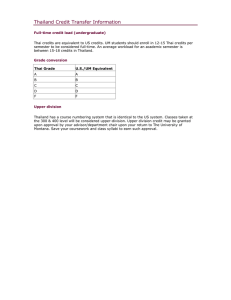

T D P

advertisement