Document 13546480

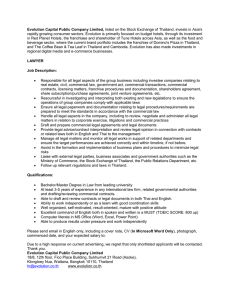

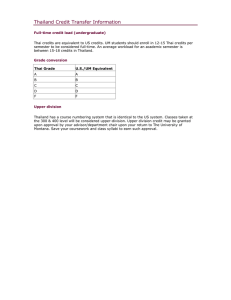

advertisement