Document 13520316

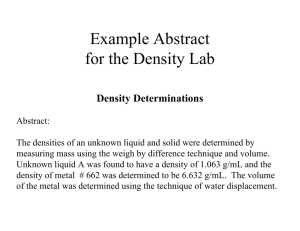

advertisement