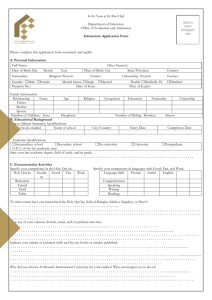

ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF IRAN

advertisement